Local landlords are selling their properties to investors amid eviction moratorium

Photo | Edd Cote

Landlord David Branagan sold his nine-family Worcester property to a Boston investor.

Photo | Edd Cote

Landlord David Branagan sold his nine-family Worcester property to a Boston investor.

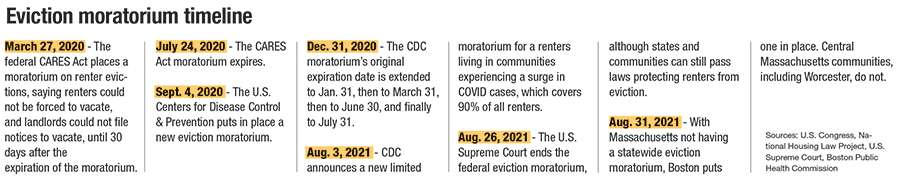

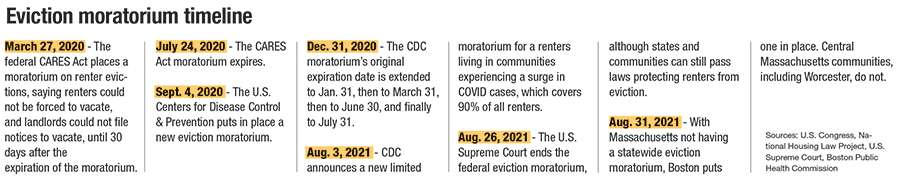

When it was established in September 2020, the federal eviction moratorium invoked by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention was meant to keep renters housed during the economic downturn of the coronavirus pandemic. About a year later, the U.S. Supreme Court has overturned the policy, but its implications are continuing to have unique impacts on the Worcester community.

For David Branagan, a local landlord who has owned property for more than 20 years, the moratorium practically ended his career owning properties, causing him to sell his two multi-family homes in Worcester and Webster.

“If I could do it over again, I wouldn’t have become a landlord,” said Branagan, who reported losing roughly $33,000 from three tenants who didn’t pay him rent during the moratorium.

Branagan said he worked with one of the non-paying tenants, a mother of two who worked as a food delivery gig worker, to try to get rental assistance, but the application was never finished. Eventually, he decided to cut his losses.

“It would cost me a fortune with lawyers,” Branagan said when explaining why he decided to sell rather than pursue the rent money. “There were just too many landmines to go through.”

In early August, he sold his nine-unit property on Vernon Street in Worcester to an LLC registered to Boston real estate investors, Kinvarra Capital.

Branagan said the investors plan to renovate the property, which he had been renting out below market price to low-income tenants.

Just 10 minutes after the deed was signed, the buyers distributed requests for all the tenants to leave, he said.

“Before the ink was even dried, they had a sheriff there giving everybody notices to quit,” he said.

Worcester flooded with outside investors

Small-time landlords selling their properties has become something of a trend this year. More often than not, they aren’t selling to other locals.

Douglas Quattrochi, executive director of Cambridge nonprofit MassLandlords, Inc., estimated two to three times as many landlords as normal were selling properties last fall, based on membership non-renewal rates.

“Investors have the money to go through with these evictions while the landlords selling can’t afford the eviction,” said Amanda Trudell, director of operations at Worcester real estate company DiRoberto Property Management, Inc. “These investors aren’t stopping anytime soon … It’s only going to keep growing, and investors are going to keep coming in.”

Trudell said the trend of bigger real estate companies buying properties from small landlords is an especially acute problem in Worcester.

In the last decade, more than 1,800 housing units have been constructed in Worcester, with 2,265 more rental units expected to become available in the next five years, according to a 2019 report by the Worcester Regional Chamber of Commerce. Of those planned units, 240 are designated as affordable.

A disappearing low-income rental market

No-cause evictions, like the one occurring at David Branagan’s former Worcester property, are on the rise, said Leah Bradley, the executive director of the Central Massachusetts Housing Alliance.

A no-cause eviction occurs when a landlord decides he or she wants the unit back for any number of reasons, such as renovations or housing a family member.

An increase in property sales in the region has played a role in incentivizing no-cause evictions and limiting affordable rents, said Bradley.

“There’s a real lack of units for those that are the lowest-wage earners,” Bradley said. “As folks are needing to leave their units, the ability to find a new unit is really compromised.”

She said throughout the county, even people with Section 8 subsidized housing vouchers are unable to find a unit within the range the voucher covers.

Renters and low-income earners are disproportionately people of color, so that population is most heavily impacted, Bradley said. In Boston, 78% of eviction filings were in communities of color, according to a 2020 study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The fight for affordable housing

As the moratorium ends but COVID-19 and the Delta variant rage on, community organizations are working hard to create a long-lasting solution to Worcester’s affordable housing crisis.

“The eviction moratorium is just a delay,” said Bradley, calling the policy a stopgap. “It’s not as if people don’t need to pay their rent going forward.”

Instead, Bradley’s organization has been collaborating extensively with state and local agencies to improve rental assistance programs, which has reached 35,000 households in the state, she said.

This spring, the state amended the program to allow landlords to apply directly for assistance if a tenant doesn’t finish an application, which would solve the issues Branagan faced. Tenants can now access assistance more directly if a landlord is unresponsive.

“We’re constantly looking at who isn’t accessing it, who’s getting denied, what are some of the things we can change in order to make it more accessible,” said Bradley, as she explained the next challenge is to increase the program’s accessibility offline for seniors and people without internet access.

CMHA is also advocating that Worcester allocate 20% of its $111 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds to create 500 affordable housing units. The city currently has $12.5 million earmarked for housing.

5 Comments