While the Massachusetts economy is doing well, tens of thousands of people still can’t find a job, because they don’t have the skills to fill a good one.

And while the Massachusetts economy is doing well, hundreds of companies find their growth stunted and their opportunities being lost because they can’t find the trained workers they need to fill the good jobs they’ve created.

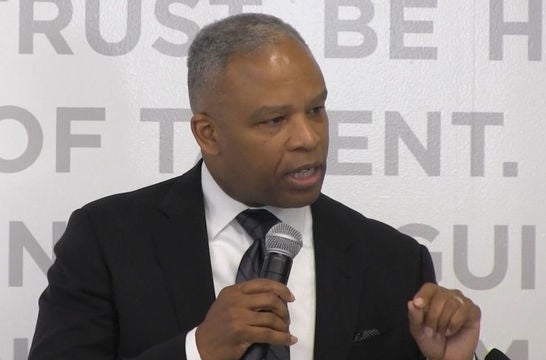

Directly in the center of these major problems, at the head of the Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development, sits Ron Walker. His job is to solve them. And he’s in a weird, but enviable, position – unlike most executives, if he puts his two problems together the right way, he’ll go a long way towards solving both of them.

Of course, the skills gap, the shortage of workers to fill the jobs of the new economy, is so well-documented that businesses know by now to go right to Labor and Workforce Development to find the people they need, right?

“Not at all,” Walker says. And he says his main goal is to be the secretary who finally breaks through to the business community, who normalizes the idea that the government workforce system is among the first places to look to find good people.

Walker’s instincts, long since instilled, are to look at his constituencies as customers, and build business models to try to serve their needs. That’s what he knows how to do. This is his first job in the public sector, after a long career in banking: customer service and corporate lending.

As Secretary of Labor, Walker sits on top of a potential powerhouse set of resources. The unemployment system and job training centers – 32 Career Centers around the state – are largely federally funded and operate under federal oversight, but Walker’s people manage them.

There are federal programs, state programs, regional programs. Acronyms abound. Walker and his team are always searching to see who’s most deserving, or newly deserving, of a share of the large, varied pots of money.

Most of the programs and offices and grants and forms and initiatives ultimately come down to two main missions – help people find jobs, and help jobs find people.

That second part is the one that caught Walker’s eye when he systematically studied the organization he took over, and then got into the field. “I went out and talked to a ton of businesses very early on. Their orders are going up, but the workforce skills they need to be successful have changed dramatically. Manufacturing is now precision manufacturing. It’s not the previous technology.

“And as we go out and talk to businesses around the Commonwealth, they’ll say, ‘I don’t know what the career centers do, what impact they will have.’ And yet, if you look at the numbers and performance of the career centers, they’re very good at what it is they do” – find jobs for the unemployed or about-to-be unemployed.

Within the 32 centers there are business services representatives, and their role is to reach out to the business community,” Walker says, and when he took over, “Everyone was saying everything was going well, but when you sit down with businesses, there was too large a gap, where too many people are saying, ‘We just didn’t know.’ “

That made him – and the governor – unhappy, and “We’ve come up with a workforce solutions model we’re calling Demand 2.0, where we are actually taking all of our career centers and business services reps and having them go out to the market, talk to the businesses out there, do what needs to be done out there.”

Walker himself has assertively sought to lead this evangelizing, in places like the Governors One meeting room at the Holiday Inn Taunton where he spoke a couple of Thursdays ago. In a roundtable with local businesspeople – one of a series he requested Associated Industries of Massachusetts help him set up – Walker lays out his goals for LWD, and then asks for questions. After the usual awkward waiting for the first question, the businesspeople give him something of an earful.

One manufacturer says she’s called the Career Center in Taunton in the past and not had good results, but she’s reluctantly willing to do it again, because “there’s no one out there” to fill the jobs waiting in her health care company. Walker says he knows there are people – perhaps untraditional, older or younger or with problems in their past but willing to stay on the path to success – there are people coming into the Career Centers that can suit the needs of this manufacturer.

If there’s one thing clear from the exchanges in the meeting room, it’s that Walker knows he’s doing things a new way – and the employers are still under the impression they’re being done the old way.

He keeps using a phrase one doesn’t expect to hear from the uber-head of the unemployment office: “We’re here to provide B-to-B (business-to-business) services…we want a B-to-B relationship.” Again, it brings to mind his professional past – he knows how to set up branches to provide for the needs of customers, and all the Career Centers are really, is branches.

David Muldrew, whom Walker hired as Employer Services Director in August, makes the point in a more specific way, asking for people’s cards, telling them, and eventually eliciting a response from a hospital HR person that’s music to Walker’s ears: “That’s good to know, that you’re a resource.”

Eventually, up jumps Eric Alberto, operations manager in the Taunton center, and as the session ends, he’s surrounded by a half-dozen employers, making the connections Walker says can fill the skills gap if his office makes the first move.

As with all the secretariats, there are the things Walker wants to do, and the things he must do. Unemployment claims have to be processed and delivered. All sorts of malfeasance has to be battled – whether it’s fake unemployment claims or employers violating pay and safety laws.

Walker himself manages a workforce of 1,400 people around the state and a budget of $43 million. About 300 of those employees work directly in the Executive Office, managing and administering the 32 career centers and various worker training, safety and labor-standards programs, along with the unemployment and worker’s compensation systems.

For an idea of the complexity, consider: the worker’s compensation department alone, one of 11 departments reporting to Walker, comprises 18 units just by itself. “It’s a lot,” Walker says with an understated chuckle – but then everything about him seems understated, which should not be misread as “laid back.”

It is not difficult to pick up on Walker’s strengths – polish and discipline. He looks like the banker he’s always been, before being sought out by the Baker transition team two winters ago. He comes across as keen but soft-spoken, put together like the IBM man he once was.

Walker started his career 30 years ago, at IBM, after playing football and studying finance at Prairie View A&M University outside Houston. Yes, in that order; both pursuits are significant in his makeup, says the secretary: “impressed on me that you had to have discipline to do math, and that discipline that he applied in the math class he applied on the football field.”

That built on the sense of discipline he got from his mom, a single mother from Mattapan. She made sure that “I focused on being a good person first,” that he valued education and that “there were no limits,” Walkers says. “She was a disciplinarian… I wouldn’t say strict, she and I would talk and she would listen as I got older. She wasn’t strict, but she was a disciplinarian.”

After school, one of his major mentors was a marketing executive named Thomas Bailey, who helped him travel the distance from city street kid and football jock to “IBM man,” at a time when that phrase still had currency, in 1985. “It was wingtips, white shirts, pocket squares.” The “IBM way” as modeled by Bailey, made him a better banker later, Walker says: “You learn professionalism, how to conduct yourself socially. That really helped to mold me – I benefitted tremendously from it.”

From IBM and Xerox on the marketing side, Walker joined Fleet Bank in 1990, and gained another role model: John Hamill, who was a role model for a lot people in New England, especially bankers. Fleet became Sovereign, and at Sovereign, Walker became V.P. of retail banking. He managed 200 employees in 38 retail branches and worked to expand Sovereign’s small-business lending – activities that have to have made taking over 32 Career Centers feel at least a little familiar.

An early experience rising through the ranks in retail management helped him understand the facts of life for an effective leader. Walker says that when he became regional executive for retail banking back at Fleet, “(My job was to) take over retail branches and I had never worked in a retail branch. One of my first experiences was visiting the (retail) business centers. I was shaking hands and stopping with and talking to the business types and the managers and I just waved to the tellers.

“I wasn’t halfway through the visit when the phone started ringing, saying the tellers weren’t happy. And of course they were right. They are important. They see the customers the most often. They are key members of the organization.”

That lesson, long since learned, informed his early days in the Secretary’s office, when he made sure he was “talking to everyone from the administrative assistants all the way up to the manager” in his Boston departments and at the career centers. “The second piece is I like to go out in the marketplace and see what people are saying there.”

He took a businessman’s view of the job ahead as Gov. Baker recruited him for Labor and Workforce Development. “I went about it like I was studying for a private acquisition. . . ” he said, something he knew a lot more about than public administration.

“In the private sector you are identifying what your model is, you’re executing and delivering on a model you identify. In the public system, rightfully so, we have a lot of stakeholders we have to make sure we’re aligned with.” Unions, lobbyists, legislators, longtime bureaucrats who know the system better than recently-hired managers – all have to be brought on board to get any results.

“The fascinating thing for me is trying to build those models within what is a complicated system. However, if you can get the right resources and direction and agenda, you can really have an impact. If we can do this well, there are a ton of people who will have jobs and be able to take care of their family, and those are the things that are important to me.”

Early on, Baker and Walker created the Workforce Skills Cabinet to better coordinate the job-development efforts of the Education, Economic Affairs and Labor secretaries. The trio (James Peyser, Jay Ash and Walker) announced $9.8 million in state grants to job training efforts at community colleges, high schools and other educational facilities to improve training equipment after a competitive process of grant proposals.

With the governor’s approval, he also created a task force to make the career centers and the Boston office better at matching veterans, youth, minorities, people with disabilities – all the groups likely to suffer long-term or chronic unemployment – with jobs in which they can stay, and thrive.

Part of that effort is to foster more and better training in “soft skills” – meaning professionalism, work habits, working well with others, communication – crucial for employers, and lacking in too many of the prospective employees they interview.

But it’s obvious, from a conversation in his office atop the McCormack Building or out in the hustings of Taunton, that reframing the work of the career centers is his main mission: evolving them from “The Unemployment Office” into true retail operations for businesses sorely short of workers.

Walker says he’s found centers where leadership badly needed a change, and others he can use as models systemwide. “This is a process that is really like taking over branches at a bank, where you really have to go in and you have to talk about culture, you have to make sure the initiatives are aligned, you have to develop key performance initiatives, but all under the assumption that everyone wants to be successful at this and … have clear results.”