While the economy was growing into the longest economic expansion in the nation’s history, most Worcester County neighborhoods missed out – not only failing to capture rising income and attracting new residents but even going backward in many cases.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

While the economy was growing into the longest economic expansion in the nation’s history, most Worcester County neighborhoods missed out – not only failing to capture rising income and attracting new residents but even going backward in many cases.

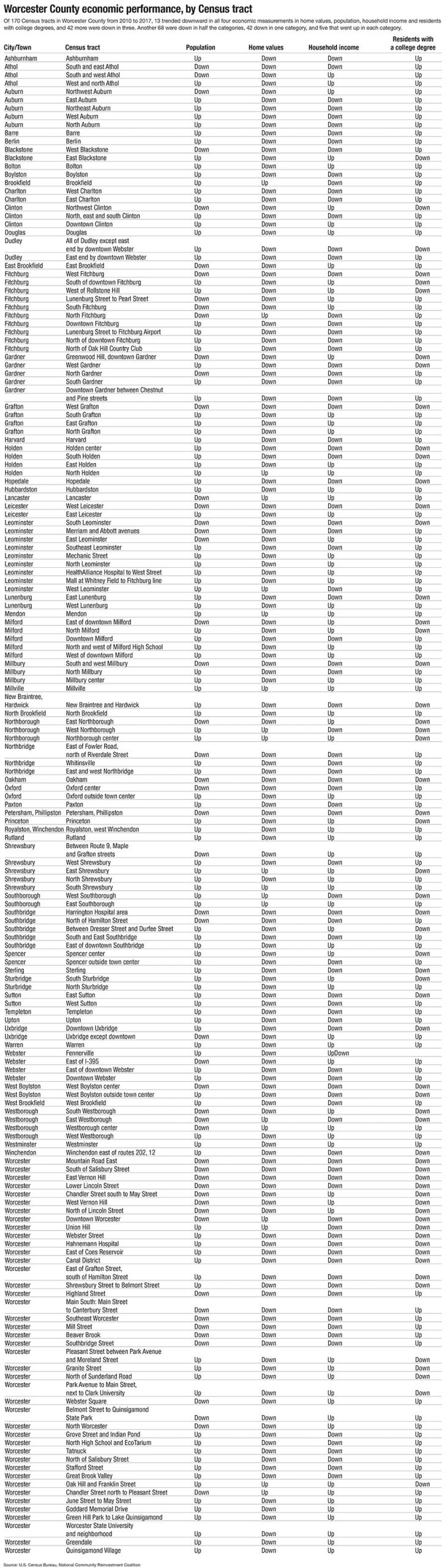

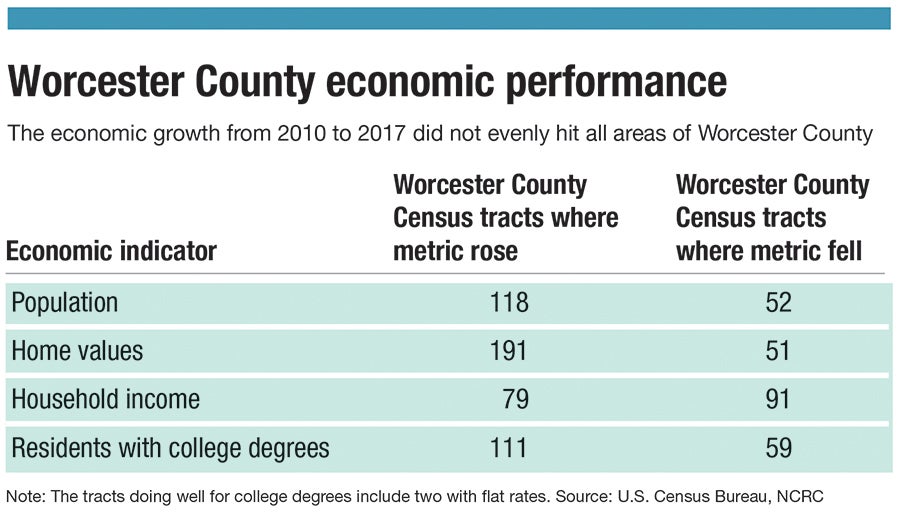

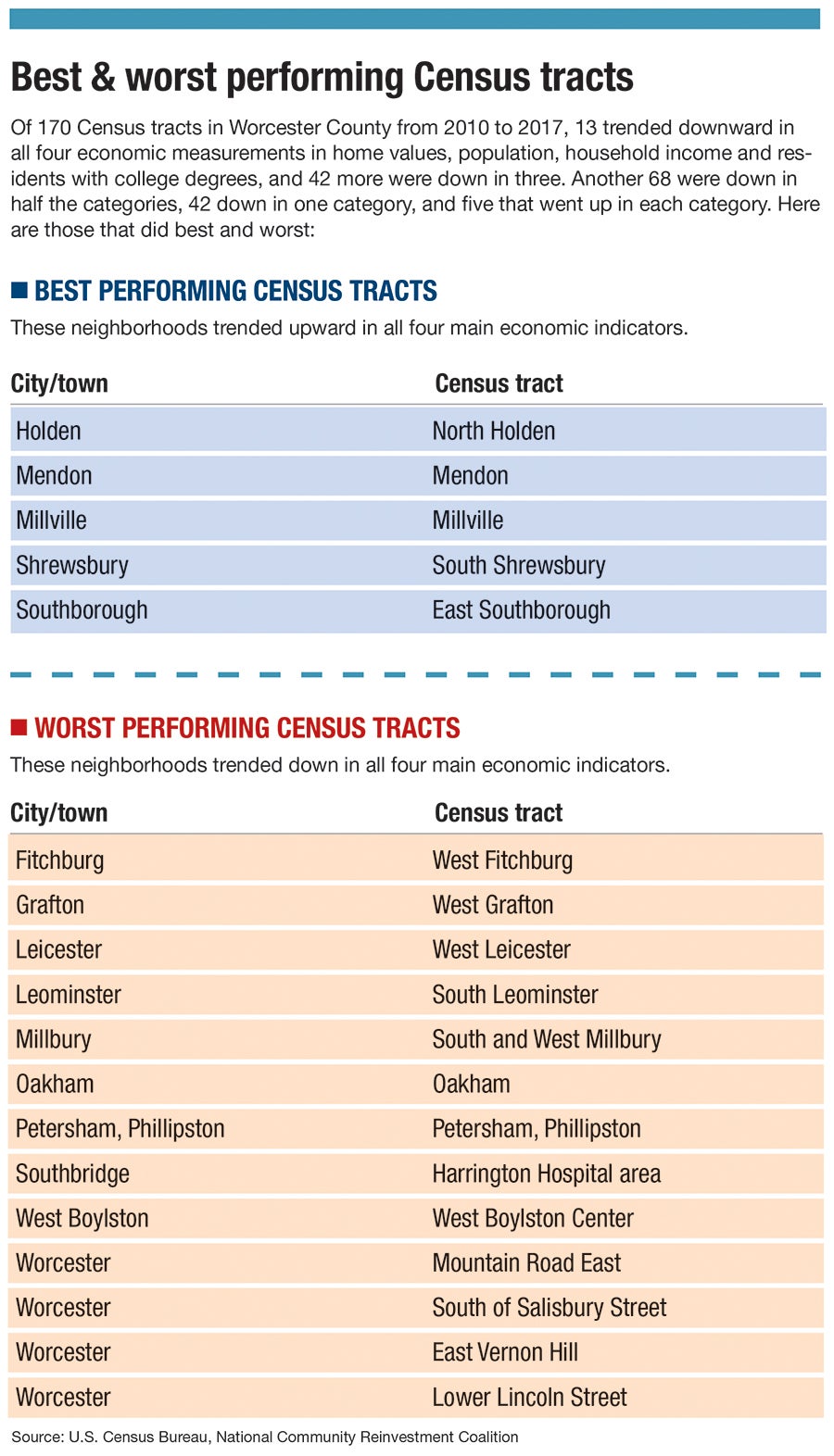

Looking at four key economic indicators of population growth, rising home values, increasing household income and residents with college degrees, 55 of the 170 Census tracts in Worcester County had decreases in three or all four categories, according to a Worcester Business Journal analysis of data from 2010 to 2017 compiled by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, a Washington, D.C. economic research and advocacy group.

Beyond those years in which the nation’s economy was in a small but steady incline, the poorer areas of Worcester County appear to suffer worse in the coronavirus-related economic recession started in February, with Census tracts in places like Fitchburg and the city of Worcester having unemployment rates above 30%.

“This is the story of being left behind,” said Randy Albelda, an economics professor at UMass Boston and a senior research fellow at its Center for Social Policy.

Even though low unemployment rates were common across communities pre-pandemic, the data from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition shows it didn’t lead to broad economic prosperity in Worcester County.

In total, 13 of Worcester County’s 170 tracts – including parts of Fitchburg, Leominster, Grafton and Southbridge – saw reversals in all four key economic indicators. Another 42 neighborhoods went down in three of the four economic measures.

Looking at one key metric, 19 – or 11% of the total – saw home values rise.

“It’s completely a story of divergence. It’s like a tale of two Massachusettses in some ways,” said Smriti Rao, an urban economics professor at Assumption University in Worcester, contrasting the Boston area’s prosperity to further away areas.

“Some parts of Worcester are getting incorporated into that Western Massachusetts story, which is one of being left behind,” Rao said. “It’s really a case of a part of Massachusetts that was left behind by the recovery.”

Not gentrification but disinvestment

It's a buzzword conveying both the rising prosperity but also potential for displacing residents or businesses as a result: gentrification.

Most neighborhoods in the city of Worcester are instead experiencing something entirely different: disinvestment.

The National Community Reinvestment Coalition issued a report in June highlighting urban areas and put some neighborhoods into one of two categories: gentrification or disinvestment.

Worcester did not fare particularly well. Three neighborhoods fit the coalition’s definition for gentrification: the north side of the Chandler Street corridor west of downtown, Quinsigamond Village and Stafford Street, which runs to Leicester.

Those three tracts make up 12% of the Worcester neighborhoods the coalition considered eligible for gentrification – that is, they were relatively poor to begin with. The coalition considered a neighborhood eligible for gentrification if it was in the lowest 40th percentile of median household income and home value for the area. Other neighborhoods were either better-off to begin with or had worsening economics.

In Boston, by comparison, 21% of neighborhoods were deemed gentrified. In Hartford, it’s 18%, and Providence it’s 8%.

Most cities – and even most parts of cities that did well – did not experience rising economic fortunes, the coalition’s report said.

MassINC, the Boston-based research nonprofit studying economics in cities like Worcester and Fitchburg, has previously highlighted a lack of financial help for such neighborhoods.

The state’s Gateway Cities – ones like Worcester and Fitchburg that tend to have diverse populations and more challenged economies – have missed out on $100 million annually in federal community development funds compared to 30 years ago, according to MassINC. In the last two decades, such funds to Gateway Cities have fallen by half.

Those funds used to help pay for a wide range of initiatives, from buying and fixing foreclosed or abandoned properties, to repairing roads or sidewalks, installing new street lights or planting trees, according to MassINC.

“Whatever it is, you need resources to be able to respond accordingly,” said Ben Forman, MassINC’s research director.

Worcester County’s cities didn’t keep up in population growth with their suburban counterparts, despite a period of time when urban living has generally been seen as more appealing and a way to draw young professionals. Worcester, for example, grew by 2.2% and Fitchburg and Southbridge each by 0.8% from 2010 to 2017. The county as a whole grew by 2.5%. Massachusetts grew by 4.8%.

Many of the county’s poorest neighborhoods got even poorer despite the economic expansion, according to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition data.

In all, 11 of the 24 areas with median household income of less than $40,000 in 2010 had lower incomes by 2017. That includes Worcester’s downtown, Canal District, and the restaurant-saturated Shrewsbury Street and Highland Street corridors, as well as parts of downtown Gardner and Webster.

But wealthier neighborhoods weren’t always spared, either.

Worcester’s most prosperous neighborhood – a tract south of Salisbury Street west of Park Avenue – got worse in all four measures. So did Harvard, as well as the wealthiest parts of Southborough and Northborough.

Already seeing recession’s hit

The current recession technically begun in February and exacerbated by the pandemic has already hit Worcester County’s poorest neighborhoods hardest.

Four Census tracts in Worcester and Fitchburg, for example, had unemployment rates estimated at 30% or higher in June, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the analysts Yair Ghitza and Mark Steitz, who compiled a working paper using Census data to show how high unemployment rates are affecting individual neighborhoods.

Lower-paying jobs have tended to be hit the hardest during the pandemic.

In the Worcester metro area, leisure and hospitality jobs – which average around $17 an hour nationally – have dropped by 26% this year through August. Finance jobs, whose pay averages more than $37 an hour, have declined locally by less than 3% during that time.

Albelda, from UMass Boston, sees Greater Boston as one of relatively few areas nationally where job opportunities and pay did particularly well during the economic expansion following the Great Recession. Too many other areas haven’t kept up, including in regions traditionally relying on manufacturing and other jobs pay well but don’t require a college degree, she said. Those jobs are now less common.

Finding solutions

Fixes are not simple. MassINC and the National Community Reinvestment Coalition have pressed for restoring federal community development funds. Rao said better access to well-paying jobs is critical. Albelda sees a need for major interventions, including better health insurance and early education.

“Those are big solutions,” Albelda said.

Any solutions will now have to be tackled at a time when communities are facing an employment and public health crisis.

The recession suddenly erased roughly 24 years of job growth in the Worcester metropolitan area. The workforce in the area, which includes Worcester County and Connecticut's Windham County, was brought in April to the lowest level since 1996.

Employment has recovered a bit since but as of August remained down 6.5% for the year.

The biggest employment hits have taken place in the poorest pockets of Worcester County.

Downtown Fitchburg is the poorest neighborhood in the county with a household income of $17,292, a fraction of the state's median of $77,378. It had an unemployment rate in June of 25%. Great Brook Valley in Worcester, with a median household income of $19,760, had an unemployment rate of 30%.

The Census tracts in Worcester County with unemployment rates of 25% or more had higher poverty rates. Those areas' average poverty rate more than doubled the national average and nearly tripled the state rate.