With stagnant wages, frequent turnover and the growing pressure of student loan debt, human services providers face a staffing crunch that leaves them without sufficient resources to meet the needs of the state’s most vulnerable populations, advocates told lawmakers Tuesday.

More than a dozen bills were before the Joint Committee on Children, Families and Persons with Disabilities for a hearing, but a common theme ran through many of them: addressing the plight of service employees who, despite helping those with significant physical and mental needs, cannot make ends meet.

“We’re in a crisis,” said Justice Resource Institute CEO Andy Pond, who was one of several speakers to describe the situation that way. “We can’t find the staff we need or keep the ones that want to stay. In many cases, they’re forced to abandon the work that they love, thereby depriving the commonwealth of some of its most important workers.”

Several legislative solutions are on the table that both employees and employers said Tuesday would have significant positive effects, particularly a state-administered loan repayment program and an effort to reduce the wage gap between state and community-based human services jobs.

Under the proposed loan program, full-time human services employees who earn less than $50,000 per year — a higher salary than many in the field make in entry- and mid-level positions — would qualify to receive $150 per week from the state for up to four years to help defray the costs of student loans. Supporters did not offer an estimate Tuesday of how much the program would cost.

Half a dozen such workers offered personal testimony Tuesday, describing tens of thousands of dollars they owe on loans as a burden that prevents them from purchasing a house or starting a family. Some shared stories of colleagues who jumped to better-paying work in research or biotechnology, leaving fewer employees to help those in need.

“I am imprisoned by my debt and have to put my life on hold,” said Eileen Foley, a mental health clinician at NFI Massachusetts who faces more than $140,000 from earning her master’s degree. “Outside of myself, student loan debt is casting a shadow over the health field, and my concern is the barrier that student loans will put on the health care field, in turn creating a crisis.”

A similar bill, albeit with a $45,000 maximum salary threshold, was reported favorably out of the Children, Families and Persons with Disabilities Committee last session, but never cleared the Ways and Means Committee in either the House or Senate. However, Rep. Jeff Roy, who filed the House legislation this session, said he is optimistic about the bill’s chances given that close to 130 lawmakers have co-sponsored either version.

“We need to provide this type of minimal relief for these students so they can stay in this field, to encourage people to pursue this field, and to provide the resources we need to have a trained workforce to do this work,” Roy said.

Another key problem advocates want to see the Legislature address is the disparity between caretakers who work for community-based organizations and those who are directly employed by the state. Although both roles carry similar responsibilities, they said, state jobs can pay tens of thousands of dollars a year more, creating a near-constant drain of employees away from smaller, local centers.

As a result, according to Bay Cove Human Services CEO Bill Sprague, organizations are forced into a situation where “individuals with less experience are forced to care for the most vulnerable in our community.”

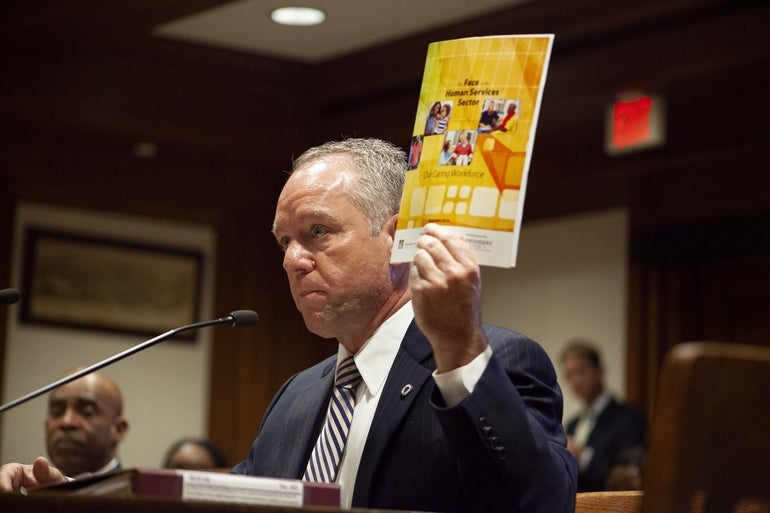

Michael Weekes, CEO of the Providers’ Council, said many community service groups — which are often contracted almost entirely by the state for service but at a rate lower than directly employed state workers — have staff vacancies of 25 to 40 percent, even as research indicates Massachusetts will need another 24,000 human service jobs to meet growing public needs.

“There’s no way that need is going to be met, so we’re going to find ourselves with people, consumers and residents that are not going to be served because we don’t have an adequate workforce to service them,” Weekes said. “It’s a problem now. It’s only going to get worse if we don’t address it.”

Bills before the committee would require the state to gradually increase its reimbursement rate to providers up over the course of five years until there is no longer a gap between state-operated and community-operated human service worker salaries.

“This is an incredibly important issue,” said Sen. Cindy Friedman, the bill’s Senate sponsor. “We are facing a very serious workforce crisis.”

The committee is also weighing a Rep. Jon Santiago bill to enshrine in law maximum client-to-coordinator ratios for the Department of Developmental Services. Because of current staff levels, according to service coordinator Stan Taraska, the department has more than 41,000 individuals eligible for support but only 496 coordinators — a roughly 82-to-one ratio. Santiago’s bill would mandate caseload ratios of 55-to-one for coordinators who oversee service for individuals with developmental disabilities.