A new amenity hoping to draw crowds from across Central Massachusetts is coming to Worcester’s Canal District.

No, not Polar Park and the Pawtucket Red Sox. Much sooner than that, the Worcester Public Market will bring a different kind of draw cities are increasingly seeing open in their neighborhoods.

Like the new ballpark, the market is a bet more people can be drawn to the neighborhood, in turn increasing the Canal District’s density and vitality.

“Everyone’s been talking about having a marketplace,” said Allen Fletcher, the developer of the market and 48 apartment units being built above it. “It’s a huge risk. These things are not slam dunks.”

The Canal District is growing but still has few large employers for lunchtime crowds and few residents – as well as little disposable income. More than one out of three Canal District residents live below the poverty line, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

That will force the market to rely on visitors from outside the neighborhood, a factor itself complicated by a major construction overhaul of Kelley Square immediately outside the building slated to begin this fall.

“There’s a reason why no one’s done this before,” Fletcher said, predicting the market will either become the city’s premiere shopping destination along with adjacent Crompton Place or become a failure.

The modern European market

Food halls, which feature a mix of often local vendors – unlike a food court more likely have a McDonald’s or Dunkin’ – are a major trend in food and retail.

Food halls now number roughly 250 nationally, according to the real estate services firm Cushman & Wakefield. The total could hit or surpass 300 by the end of next year.

By then, the food hall market will have tripled in size in just five years, according to the firm’s analysis.

Garrick Brown, a Cushman & Wakefield vice president and head of its retail research division for the Americas, doesn’t see the food hall trend as a passing fad. For food vendors, they offer lower costs and, ideally, higher foot traffic than if restaurants were to try making a go on their own, he said. For diners, prices are typically lower, with a broad array of options available.

With food halls opening in so many neighborhoods in larger cities, Brown said he isn’t surprised they’re now opening in smaller cities like Wilmington, Del., Omaha, Neb., and Greenville, S.C.

“It depends on the execution and what they put to market,” Brown said. “Just being in a smaller city doesn’t necessarily mean you won’t do really well.

“Where they’re successful,” he added, “they’re destinations in themselves.”

Food markets were once rarely seen outside denser European cities – where people can pick up a bite to eat or groceries to make into meals at home later – are spreading in cities across the country at a time when brick-and-mortar retail is otherwise struggling to survive online shopping and other shifting trends.

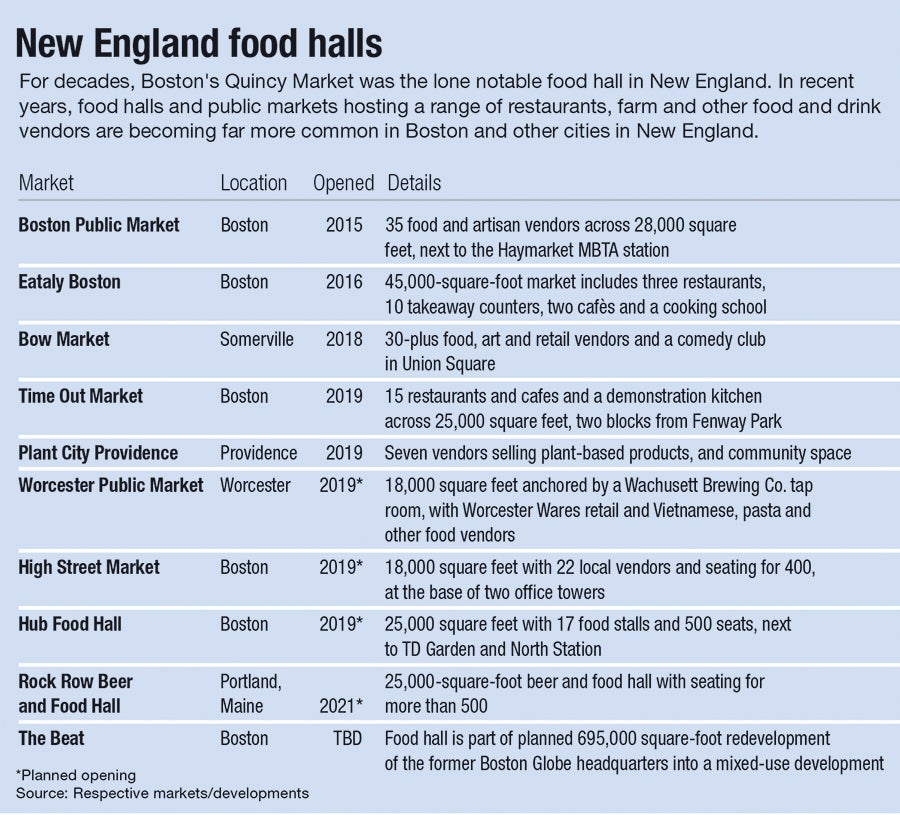

Boston has long had Quincy Market as a major tourist draw with dozens of food vendors. But it wasn’t until Boston Public Market opened in 2015 it had for the first time a market with produce.

Cheryl Cronin, the CEO of the Boston Public Market since 2016, said the market has been successful because it found the right mix of vendors and prioritized a fun experience and the right ambiance. The market is roughly split evenly between prepared foods, farms and specialty products.

“It’s not a situation of ‘If you build it, they will come,’ necessarily,” Cronin said. “You want to curate a market like this.”

The market, which stands just outside the Haymarket MBTA station, one of the transit system’s busiest, had 2.5 million visitors last year, Cronin said.

Boston Public Market has quickly been joined by a series of other food halls in Boston. In 2016, the upscale Italian food market Eataly Boston opened in the Prudential Center, replacing what had been a standard mall food court.

This June, another market opened just a mile away: Time Out Market, a few blocks from Fenway Park. Two more are on the way: High Street Place, which is slated to open this fall in the city’s Financial District, and one at the Hub on Causeway, a massive mixed-use development next to TD Garden.

These markets are capitalizing on consumers’ shifts toward higher-end food, more casual dining and an emphasis on experiences, said TJ Delle Donne, an assistant dean in the college of culinary arts at Johnson & Wales University in Providence.

“There’s a need again for authenticity in food,” said Delle Donne, calling food halls an example of a dining trend in which young diners seek out what’s unique and new, particularly to share on social media.

Beer, Worcester Wares & Vietnamese food

Smaller cities in New England are adding food halls, too.

In June, a food hall opened in Providence called Plant City Providence exclusively selling vegan offerings. In Maine, Portland has the older-era Public Market House downtown while on the edge of the city, the mixed-use development Rock Row includes a planned beer and food hall.

Now, Worcester is jumping in.

Fletcher is making a bet both that people will choose to pay to live in a new building on Kelley Square – the first such apartments in the neighborhood, with rents ranging from $1,395 for a studio to $2,295 for a two-bedroom – and that enough people will come into the market to keep vendors busy.

“Foot traffic is definitely going to be important for economic sustainability,” Delle Donne said.

The market does have an advantage with Crompton Place next door, a converted mill home to Crompton Collective, BirchTree Bread Co., Haberdash and Seed to Stem, among others.

Fletcher already has a major tenant lined up in Wachusett Brewing Co., which is planning a 3,000-square-foot taproom. Other tenants are slated to include a second location of the clothing and gift store Worcester Wares, along with food vendors selling Vietnamese, Mexican, ice cream and pasta, along with a deli, and potentially seafood.

Christian McMahan, Wachusett’s president, said the beermaker’s taproom opened last year in Westminster was so popular with those who found a deeper connection to the brand that Wachusett quickly determined it should find similar opportunities elsewhere.

“We are always trying to move the brand forward and evolve,” McMahan said, “and we saw that as a great opportunity to plant a flag in what we thought was a really unique vision in terms of a public market in Worcester.”

Wachusett’s plans for the market including brewing special beers it won’t offer elsewhere. Wachusett has been choosy about where it expands but found the food hall to be the right fit.

“The taproom plays into it because it’s rooted in authenticity,” McMahon said.

Fletcher began work just before three massive projects that’ll reshape the neighborhood: the $16-million overhaul of Kelley Square, the construction of $101-million Polar Park, and a $140-million mixed-use development on the ballpark property slated to bring hotels, shops, offices and apartments just a few blocks away.

Fletcher, a past president of the neighborhood group the Canal District Alliance, laments the inconvenience the Kelley Square construction will bring and doesn’t expect the ballpark to make or break the Worcester Public Market.

“It’s not going to be our silver bullet,” he said.