Converting an office building into an apartments can quickly turn into a logistical and financial boondoggle.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

More American office space is sitting empty than at any point since 1979, according to a January report from New York-based Moody’s Analytics.

A WBJ analysis shows Central Massachusetts is no exception. Data from CoStar, a real estate information firm based in Washington, D.C., reveals at least 44 properties in the area have had 10,000 or more square feet of office space for lease for more than two years.

At the same time, the region is facing a housing crisis. Gov. Maura Healey identified the state’s housing crunch as her top priority in a March interview with GBH News, and an April study by Forbes Advisor, a financial news and information service in New Jersey, found Greater Worcester was the third-most competitive rental market it studied.

Forbes found Worcester had the second-lowest vacancy rate of examined areas, at 1.7%, with a median price of $1,995 per rental, almost $200 higher than the study's median price of $1,804.

With an abundance of empty offices and a lack of supply of apartments, it may seem like converting offices to residential units would be an obvious solution to both problems.

Not so fast, say real estate insiders. While it may seem like a simple solution, attempting to convert an office building into an apartment building can quickly turn into a logistical and financial boondoggle.

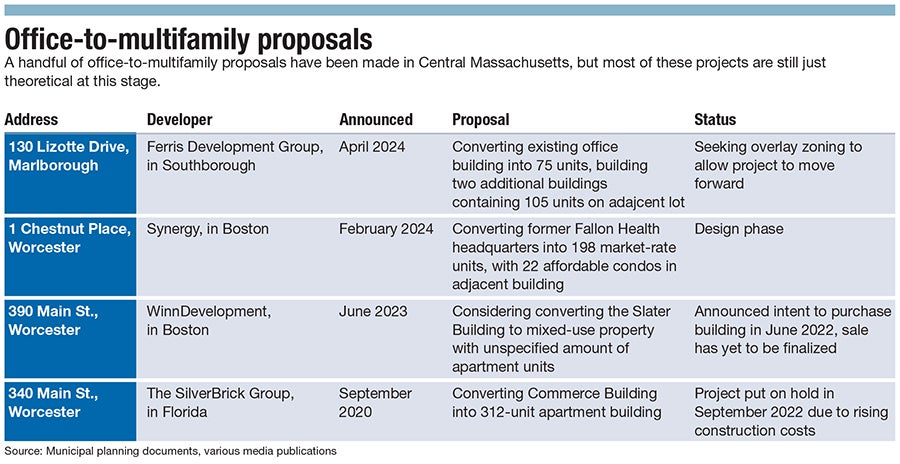

A few developers have proposed office-to-multifamily projects in Central Massachusetts, ranging from urban structures in Worcester to suburban buildings in Marlborough. Others are standing on the sidelines, waiting to see how these plans play out.

Infrastructure issues

The untrained eye might see an expansive, open-plan office space as a blank canvas, easily filled by apartment units. But to a more experienced viewer, the infrastructural challenges to conversion quickly become apparent.

“Depending on the shape of the building, the cores will be located in one or two vertical shafts all the way through the building,” said Jim Bartholomew, vice president of R.W. Holmes Realty, a commercial real estate firm based in Wayland. He is referencing the interior structures containing wiring pipes, elevator shafts, and stairwells. “Once you start running hallways or building separate units, that’s going to make it much more difficult to bring plumbing to each unit.”

All that extra water, sewer, and electrical infrastructure raises costs.

“If it’s a concrete floor building, you’re going to have to core through that, which causes significant expenses,” he said. “Water lines are one thing, but sewer lines are just a whole other operation. It’s just much easier to put that in a building that has a shell of an envelope versus one that’s already established as an office building.”

Heating and cooling is another issue.

“An office building has one central system. It's one system that heats and cools the whole building in different zones,” said James Umphrey, president and principal owner of Worcester-based real estate firm Kelleher & Sadowsky Associates. “But the HVAC system is not designed to be split up into 200, 1,000-square-foot units.”

Seeing the light

Even in today’s housing market, you won’t find many people willing to live in a windowless apartment. But with large, square buildings, it can be difficult to design floor plans with enough windows for each unit.

“Even if a building was 50 feet in depth going along the window line, to be in a position to build a 1,000-square-foot unit, it would have to be 50 feet by 20 feet,” said Umphrey. That’s an awkward shape for an apartment.

Even commercial buildings with high vacancies may not be entirely empty.

“Any tenants that are still in that office building are going to have the right to stay there through the term. It would just add another expense to it to have to buy them out,” he said.

All these obstacles can be overcome for the right price, but with sky-high construction and labor costs, developers aren’t exactly eager to pull the trigger.

Downtown development

Logistical and financial challenges might explain why office-to-multifamily conversions have historically been a rare phenomena. These types of projects have only made up approximately 1% of completed multifamily projects over the past 20 years, according to a March 2023 study conducted by CBRE, a global real estate company based in Dallas.

Still, attempts are being made to convert downtown Worcester office buildings into housing. The most recent proposal involves One Chestnut Place, the 11-story former headquarters of Fallon Health. Synergy, a Boston-based real estate firm, purchased the building for $10.5 million in March 2023. In February, City Manager Eric Batista’s tax increment exemption proposal stated Synergy sought to build 198 market-rate apartments in the building, with 22 affordable units next door.

Synergy declined to be interviewed for this article.

Construction is scheduled to begin this summer, but if delayed, it wouldn’t be the first Worcester office-to-multifamily proposal to get stuck in limbo.

Property purgatory

In June, WinnDevelopment, a subsidiary of Boston-based management firm WinnCompanies, announced plans to convert the historic Slater Building at 390 Main St. into a mixed-use, mixed-income development featuring a to-be-determined number of apartments.

Almost a year later, the sale hasn’t been finalized, according to Worcester District Registry of Deeds records.

In a statement to WBJ, Winn reiterated its commitment to the project, while hinting at a need for more financial and municipal support.

The Commerce Building, located at 340 Main St., and two nearby parking lots were bought by the SilverBrick Group, a Florida-based real estate firm, for $14.4 million in 2020. SilverBrick won municipal approval for the project, but now appears to be attempting to sell the property. A CoStar listing for the site says it is under agreement for purchase. The company did not respond to a request for comment from WBJ.

Beyond these three properties, Umphrey doesn’t see as much potential for office-to-multifamily conversions in Worcester as other regions facing larger struggles with unused office space.

“In Worcester, the other buildings from a vacancy perspective are doing really well,” he said, referencing buildings like 100 Front St., which he said has only 2,800 out of 2750,000 square feet available, and 120 Front St., which he said has 10,000 square feet vacant out of 165,000.

Suburban situation

Urban areas don’t have a monopoly on underutilized or empty office buildings.

“There’s no doubt that when you start getting into suburban space – the Marlborough area, Southborough, and down even further – there’s definitely a lot of space and vacancy,” Umphrey said.

A prime example of underutilized office space is the five-story building at 130 Lizotte Drive in Marlborough. Empty for more than a decade, the building was bought in March for $4.48 million by Ferris Development Group, a Southborough-based real estate developer. Ferris wants to build 75 units in the existing building and develop two additional buildings containing 105 units on an adjacent parcel.

Suburban conversions can bring their own challenges. While downtown Worcester is already zoned for multi-family housing, 130 Lizotte sits in an industrial-only zone. Ferris is seeking an overlay zone which would allow the project to begin to move forward.

Not a cure-all

Office-to-multifamily conversions are unlikely to be an easy fix to housing problems, according to the CBRE report.

“Elevated multifamily demand on its own is not enough to justify the cost of conversion in most cases,” the report reads, “Successful conversion candidate buildings exist in a rare intersection of supply, demand, and cost characteristics, in which the primary factors tend to be related first to cost of conversion and second to office/multifamily demand.”

But Bartholomew is keeping a close eye on these proposals, including the Ferris project. Bartholomew’s employer, R.W. Holmes, works with Ferris.

“It's going to be fascinating to watch. I think there's certainly a pent up demand. A lot of these owners want to figure out how to make their building work,” he said. “There's going to be a lot of eyes on these projects, and it's going to be very interesting to see how they play out and in how they're received.”

He’s hopeful if progress is made in Worcester or Marlborough, more developers will emerge.

“Once we go down that route, I think if they're halfway through a [conversion] project, and it's looking successful, you'll see people lining up to do this,” he said. “Until that point, you know, I think it's very difficult to pull the trigger and be the first out of the box.”