Christmas tree farms were taken by storm last year, as shoppers jumped at the chance to partake in a relatively safe, outdoor holiday activity. Local farms sold out their stock in a fraction of the time they’d expect in a normal year.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Christmas tree farms were taken by storm last year, as shoppers jumped at the chance to partake in a relatively safe, outdoor holiday activity. Local farms sold out their stock in a fraction of the time they’d expect in a normal year.

“It was probably the best year we’ve ever had,” said Dave Morin, past president of the Massachusetts Christmas Tree Association and owner of Arrowhead Acres in Uxbridge, an event venue and Christmas tree farm.

Arrowhead nearly doubled its usual sales last year, Morin said, and probably would have had it not been for inclement weather on the last weekend before the Christmas holiday. That’s no small feat for someone who, like Morin, first began planting Christmas trees around the year 1986.

Now, Morin, like other Christmas tree farmers in Massachusetts, is playing catch-up from such a busy season. He’s cleared more land and planted four times as many trees as he would in a normal year, hired about a third more employees than he did last year, and purchased new equipment in anticipation of increased demand. At the same time, he’s juggling pressure from ongoing supply chain issues raising the cost of doing business, including purchasing equipment, as well as minimum wage and fuel prices.

“The materials that go into these things are going up,” Morin said.

As a result, despite increased demand, which he expects to continue into this season, he’s raised the price of his pre-cut trees to $75, he said, although he said it’s still lower than most choose-and-cut farms, and especially compared to increasing price tags on artificial trees, which have been subjected to the same economic issues as other goods sold in stores this holiday season.

Seller’s market

The National Christmas Tree Association reported sales nationally last year occurred earlier and took place at a faster rate, but nationally demand wasn’t necessarily higher. It was complicated, the association said in its review of the season, because of constraints on supply.

Still, the assessment concluded 2020 was a great year for Christmas tree farmers, in general, and found something else: The live tree consumer demographic had shifted. Per the report, nearly 40% of live trees were purchased in 2020 by people who lived in urban areas, an 8% increase from the year before. The average age of a live tree consumer was 38, four years younger than in 2019.

The report did not draw any conclusions about why this shift happened, but conjectured it may have been because of COVID pandemic-related restrictions. The association urged Christmas tree growers to keep in touch with these buyers and make sure they are able to easily order trees again in the future.

Highfields Christmas Tree Farm in Grafton was one such local farm to feel the unexpected 2020 rush. Joseph Meichelbeck, who owns the farm, said last year the farm was sold out of trees by midday on the Sunday after Thanksgiving and had to shut down. For him, that’s in the realm of selling 500-600 trees.

“We had record demand,” Meichelbeck, who previously spent his career working in finance. “It was crazy. People were just wanting to get out of their house.”

Unlike Morin, though, Meichelbeck did not plant more trees than usual this year, noting it takes eight to 10 years for new trees to mature enough to sell. At the moment, he has about 5,000 trees in the ground growing.

“We’re certainly in a seller’s market right now. There’s no question,” he said.

Staying on top of the market

The apparent surge of popularity in farm-fresh Christmas trees is taking place against the backdrop of an evolving industry.

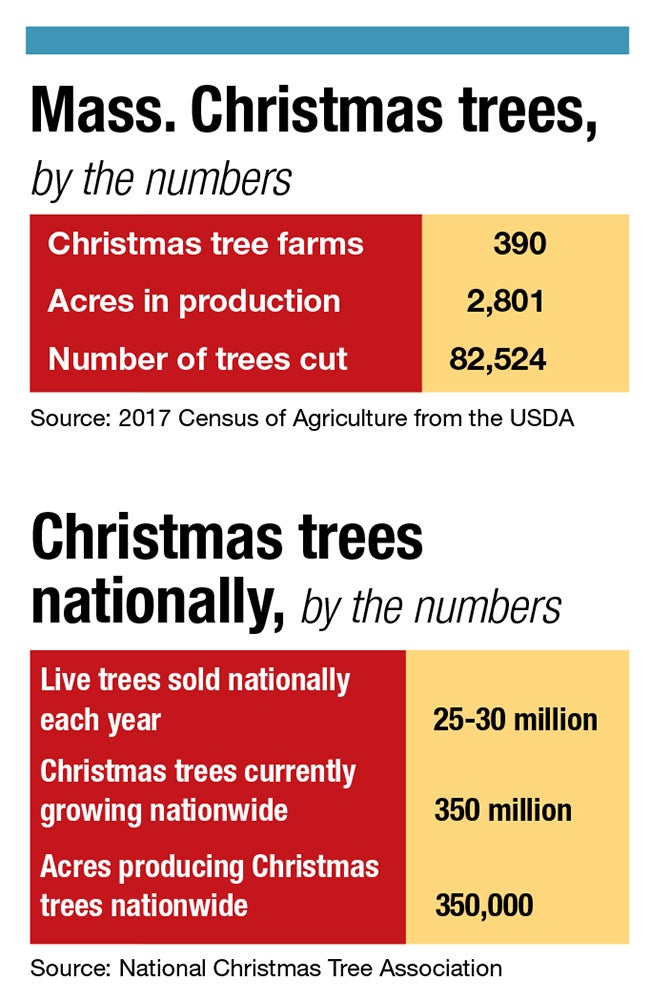

The average age of farmers across the country is increasing, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2017 Census of Agriculture, coming in at 57.5 as of that census, up 1.2 years from 2012.

Among Christmas tree farmers in Massachusetts, Meichelbeck said the average age is probably more than 60. As farmers’ ages increase, so will the number of farms available to change hands in the coming years. While a younger generation of farmers have been showing interest in produce and flower farming in Central Massachusetts, getting into tree farming is a bit of a different story.

While a farm can turn around a produce crop in less than a calendar year, it can take up to a decade to see a profit from Christmas trees.

At the same time, the operational aspect of running a holiday-oriented farm business has changed, with farmers now diversifying their offerings. What in previous decades may have been a straightforward choose-and-cut tree farm is now a family-outing destination, where farmers increasingly offer refreshments, wreaths, or even a gift shop.

These aren’t necessarily hardships, but they do represent a change and a more involved day-to-day business model.

Davagian Tree Farm in Sutton provides precisely those kinds of perks, which owner Jan Davagian said were added on over the years. For her, it’s been a welcome expansion, and she enjoys helping to hand make the additional items the farm sells.

“We have a great time,” said Davagian, whose family is in fourth generation working the farm.

That gift shop operation allowed the farm to stay open longer last year, too, she said, despite selling out of trees in two weekends.

Davagian Tree Farm increased the number of trees it planted this year, she said, but not as a reaction to last year’s rush on products. Rather, she said, the farm has been steadily growing its tree stock from year to year. The farm now has seven acres devoted to tree growth, and workers plant in the realm of 300 to 500 trees per year, depending on space.

That number of plantings is reflective of how many trees the farm sells on a given year, Davagian said.

As for differences this year, Davagian is looking forward to having her staff back and softened pandemic restrictions. In 2020, she said, employees were unable to work because of health concerns and worries about exposure during the late fall and early winter coronavirus surge.

Overall, going into the 2021 season, her spirits are up.

“It’s a very pleasant, fun business to be in,” Davagian said.