Talk of CO2 shortages has become commonplace among brewers in Central Massachusetts.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

For two days in early September, Wormtown Brewery in Worcester went without carbon dioxide. The brewery could still brew beer, but it couldn’t do many of the vital processes that get beer from the brewery to the consumer – can, bottle, purge tanks and glassware, carbonate – because its tanks stood empty.

There’s been a near-constant fear for brewers that the shortage of CO2 for the previous two-plus years will leave them stranded like Wormtown was for those few fateful days: lurching and waiting, trying to figure out how to get themselves back on track. While the short hiatus of gas wasn’t detrimental to Wormtown, it did act as another reminder we’re living in a global economy with its supply chains squeezed and at any moment what seems like a little problem or worry could balloon into catastrophe.

It’s a “reminder that the pre-COVID the supply chain was well orchestrated,” said Ben Roesch, Wormtown’s brewmaster and co-founder, said.

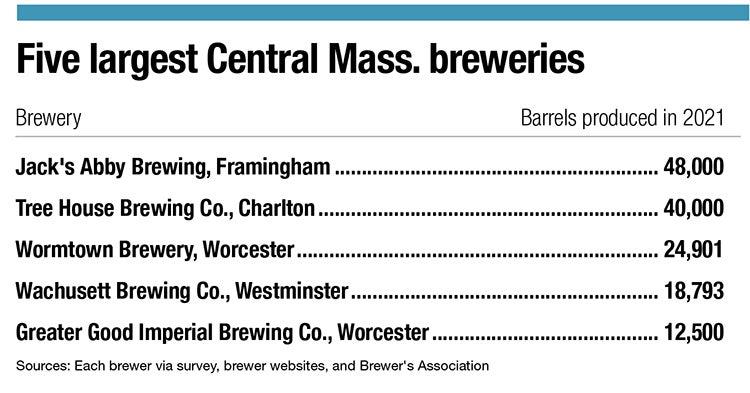

Talk of CO2 shortages has become commonplace among brewers in Central Massachusetts. While Everett-based Night Shift Brewing's move away from producing its own beer at its own facilities in Everett to contracting its operations to Jack’s Abby Brewing LLC in Framingham caused a stir because Night Shift announced it didn’t have any CO2, the reality was the shortage had been around since before the pandemic. There was a short supply of gas for some time, but no distributor had run out and until Night Shift announced its move away from production, no one in the general public really knew about the issue.

But brewers like Matthew Steinberg of Exhibit ‘A’ Brewing Co. in Framingham were already getting warnings to be ready for possible interruptions.

Steinberg received notice as the pandemic began that gas would be tight but his contract would be honored. He just needed to be more cautious with his CO2 use.

“Understand this is a consumable product and may not be readily available, and that you should do your best to conserve and use as little as possible for your needs,” Steinberg said.

A vital ingredient

What the Night Shift news did do is it let consumers know about one of the many struggles brewers were having with the supply chain, which has been in various stages of disruptions since COVID-19 shut the global economy down in March 2020. The systems once in place to move goods around the world were stalled and backlogged, causing delays and rising costs as well as disrupted availability. It sent the global economy into a tailspin it’s still not recovered from.

“There is definitely pretty extreme tightness in the marketplace,” said Sam Hendler, co-founder and CEO of Jack’s Abby. “I can say for us, we're on allocation at a reduced amount of CO2 we can use compared to our contracted amounts. But we haven't run out. We have come close a few times this summer, but we have managed to stay in stock with CO2.

“I can't get my supplier to fill my tank,” Hendler continued. “They keep me from running out, but they are giving me fills that are 30% of my tank, 40% of my tank, 20% of my tank, not 100% of my tank.”

That’s a nervous place to be in for a brewery. Brewers have to navigate moving beer, packaging it, and keeping it fresh and need to have some assurances they won’t run out of CO2 when they need it most. It’s especially important for a brewery like Jack’s Abby, which not only brews its own beer but has a contract to fulfill with Night Shift. A shutdown because of CO2 would then set back Jack’s Abby own chain of supply. And if it did run out, a quick fix would be to have gas delivered, but that would come at a huge cost.

“Spot market rates [for CO2] in early August, I was quoted for a spot delivery at 1,200% increase to my normal contracted rate,” Hendler said.

While most delays and shortages have become commonplace, a CO2 shortage still seems like a strange place to be in when there’s no shortage of CO2 production around the world.

The gas is a byproduct of manufacturing, and a lot of those businesses capture the gas as a secondary product to sell.

But, unlike their main business, it’s secondary by nature and not viewed as a vital cog in the system. So, when an ammonia plant in Canada has issues with its carbon capture system or delays in its production, then CO2 supplies are diminished and strain is put on other sources to move the gas to producers who need it, causing a kink in the global system.

While beer drinkers know beer is made of malt, hops and water, they don’t realize that CO2 is an ingredient as well and needs to be pure. Some CO2 capture can bring impurities like rust and oil. CO2 needs to be cleaned and stay contaminate-free for brewers to use it to purge tanks and packaging so beer isn’t oxidized and losing flavor while resting. Then, the beer needs to be pumped with CO2 so it’s carbonated. If there’s impurities in the CO2, they’re passed on to the consumer.

Solutions, old and new

Steinberg took action when he was informed there might be limits to what CO2 he gets or the supplier could run dry and not be able to honor the contract.

“The one thing it has done for us, and this is something we have been doing for the last year and a half, is being more reserved with our usage and being more cognizant of the fact that we want to not use as much CO2 as we possibly can,” Steinberg said. “It's a greenhouse gas that we understand is not the most positive thing for the environment, so we do our best to conserve as much CO2 usage as possible and we do that with a variety of processes.”

Steinberg, who has more than 25 years of brewing experience with stints as the head brewer at Offshore Ale on Martha's Vineyard as director of operations at Mayflower Brewing Co. in Plymouth before going off on his own, tried some different brewing techniques to conserve CO2.

He invested in spunding valves that seal fermentation tanks so the CO2 the beer produces while fermenting doesn't escape and instead works its way back into the beer.

It’s an old German technique that’s been around for centuries and used more prominently in lager brewing, which is why Jack’s Abby does it, claiming it makes better lagers while conserving CO2.

For Steinberg, all of the noise about gas shortages means it’s time for breweries of varying sizes to look at innovating. He said only a few of the bigger breweries have begun testing out CO2 capture systems, which collect the gas as it escapes during the brewing process, filters it, and puts it back into the brewery’s gas system. The Alchemist in Stowe, Vermont, has been doing it for a few years, and Tree House Brewing Co. in Charlton put in a system as well.

If the larger breweries implement and refine the CO2 capture technology, those systems could be cheaper for smaller breweries and more widespread, Steinberg said.

“A brewery the size of a 20,000-to-40,000 barrel brewery – and there are a few in that category in Massachusetts – they should have been purchasing this reclamation technology five years ago,” Steinberg said. “It wasn't [that] it is just coming out; it wasn't ready for a smaller brewery, but CO2 reclamation isn't necessarily a newer technology; but it is newer to the breweries that are smaller.”

Even reclamation systems need time to get going so that they can become operational and begin to pay for themselves, so breweries need to find short-term answers for the CO2 shortage.

Wormtown has begun exploring using nitrogen instead of CO2 to purge tanks and other vessels, but with that comes another cost and more gas tanks, because the company is bringing in a variety of gases instead of one.

While for a long time brewing was viewed as a three ingredient process with shortages and issues related to farming (hops and malt) and water quality, the sector has become even more ingrained in the global economy and supply chain with the need for aluminum for cans, glass for bottles, and packaging materials for moving product to the consumer. Now, it’s also in the gas game, and there’s no shortage of issues awaiting breweries as we still untangle from a pandemic and the havoc it wreaked on our once-vaunted supply orchestra.