More than two years after Worcester city officials announced the Pawtucket Red Sox were moving to the Canal District, there is no formal lease agreement legally obligating the team to come to Worcester.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

More than two years after Worcester city officials announced the Pawtucket Red Sox were moving to the Canal District, there is no formal lease agreement legally obligating the team to come to Worcester.

The city also lacks a binding agreement with Boston developer Madison Properties to build a multi-million mixed-use project just outside the ballpark, which the city is relying heavily upon to create new tax revenue to allow the city-owned Polar Park to pay for itself.

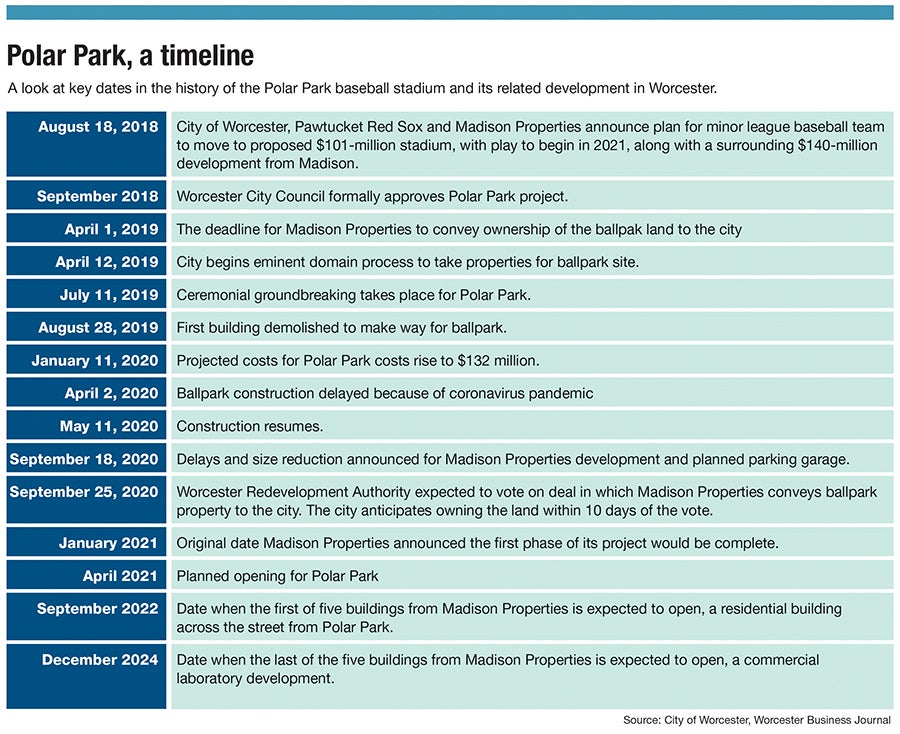

That development has been delayed so the earliest completion, for a 225-unit residential building, won’t take place until September 2022, when the original announcement in 2018 called for the first phase of Madison’s development to open in January 2021. A parking garage being relied on for game parking has also been reduced in size, with a delayed opening.

And about six months before the minor league baseball team is scheduled to begin play in a new $132-million public stadium, the city government is only now obtaining the property on which the ballpark sits, about 19 months after the original deadline for it to obtain that deed, even as construction on the project is well underway.

While this lack of formal agreements is unusual and behind schedule, they don’t mean the PawSox aren’t moving to Worcester or the mixed-use project won’t happen, especially because the team, the city and the developer all have been very vocal and public about their commitment to the massive development. The PawSox, for example, held three Worcester ceremonies in the span of one week in August – two for construction milestones and another to unveil the jerseys the team will wear after it moves.

However, the lack of signed documents does give the PawSox and Madison negotiating power over the city, at a time when the construction costs are over budget and the coronavirus pandemic coupled with economic uncertainty calls into question the near-term viability of the surrounding development.

“Once the facility is built, the municipality has zero leverage,” said Marc Edelman, a law professor who specializes in sports law at Baruch College in New York. “As a city, you want to lock in the team that would play there before you build the facility. It’s a question of which side should bear the risk.”

Worcester City Manager Edward Augustus, who has spearheaded the project for the city, has repeatedly said the guiding principle for the city is the stadium will pay for itself. He has stated previously to WBJ the COVID-19 pandemic will have an impact on the stadium’s cost and completion timeline, although it was difficult to give specifics amid the uncertainty caused by the pandemic. The last time he gave a formal cost update to the Worcester City Council was January, when the stadium cost increased from $101 million to $132 million, and the anticipated investment by Madison Properties on its surrounding mixed-use development was lowered from $140 million to $125 million.

More broadly, the pandemic has left questions of whether next baseball season could even be played or, if so, whether fans will be allowed at full capacity. The 2020 Minor League Baseball season was canceled entirely, while Major League Baseball is playing a truncated season.

“You’ve got a bunch of significant obstacles,” said Nellie Drew, a sports law professor at the University of Buffalo and director of the school’s Center for the Advancement of Sport. “You always have risk. These [projects] are by definition high-risk. You’re building, and you’re hoping people are going to come."

Anticipated cost overruns & who pays for them

When the cost of the Polar Park was last estimated in January at $132 million, it was already the second-costliest minor league ballpark ever built, adjusting for inflation, according to a WBJ analysis of ballpark finances across the country. Another $19 million in cost overruns and Polar Park will pass the $150-million Las Vegas Aviators stadium as the most expensive ever.

That was before the coronavirus pandemic threw the cost and construction timeline into disarray.

“I can say with confidence there will be impacts, and we will share them with the council when we fully understand,” Augustus told the City Council in May.

The construction of the stadium was shut down for almost two months in April and May in an effort to stem the spread of the coronavirus. To make up for that lost time, PawSox Executive Vice President Dan Rea said in a WBJ interview in August construction crews have been working double shifts over the summer, so the city and the team can still meet the anticipated opening date in April 2021.

On Sept. 18, Augustus said in a report to the Worcester City Council the ballpark construction team will meet the April 2021 opening deadline, describing a Herculean effort by all parties involved.

Who pays for the cost overruns – the city or the team – will come out at the negotiating table.

After the team agreed in 2018 to move to Worcester in 2021, the city and the team never had a specific deadline for when they would finalize the lease agreement for the team to occupy the stadium. Typically, though, a government wants that deal complete before it starts sinking money into construction costs, said Edelman, from Baruch College, so it can maintain its negotiating leverage.

“There’s kind of a poker game, and the public usually has a bad hand on that,” said Joel Maxcy, a sports economist at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

City spokesman Walter Bird said it would be more unusual for a lease to be completed at this stage of a project. In the meantime, the initial agreement from August 2018 between the city and team serves as a governing document between the two sides.

“The base lease has been drafted but operational decisions like public access logistics, parking coordination, and shared advertising assets, continue to be fleshed out as the construction takes shape and we’re able to see first-hand how the entire development interconnects,” Bird said.

Experienced negotiators

The 2018 memorandum of understanding between the city and PawSox said the team will be responsible for all construction cost overruns. That initial agreement says neither side shall be responsible for so-called force majeure events, a legal clause for unforeseen events such as a pandemic. But that clause was to be defined in the lease, which hasn’t been signed.

When asked, the team didn’t comment on whether it’s committed to picking up all the extra ballpark construction costs as spelled out in the memorandum of understanding, instead referring questions to the city. The team also declined to comment on the lack of a signed lease to move into the stadium.

When asked about if the plan is to still have the team pay for all construction cost overruns, the city said the team’s obligations in the memorandum of understanding remain.

“The team and city are working collaboratively on the construction of Polar Park to ensure it is a ballpark that makes the community proud,” Bird said. “We have also worked to overcome COVID-19 delays and obstacles together as partners, while still being ready for an April 2021 Opening Day.”

In January, when the construction costs on the stadium first rose from original estimates by $9.4 million, the team said then it would to pick up those extra costs, although the city agreed to give the team a portion of the facility fee collected on the price of tickets – money originally slated to go to the city for the stadium upkeep.

When governments negotiate with businesses – especially those like the PawSox who have owners and executives experienced in negotiations – public officials are typically at a disadvantage, said Jodi Balsam, who teaches sports law at Brooklyn Law School in New York.

“They’re not negotiating from a place of business wherewithal and resources,” she said of the city. “They’re elected officials negotiating on behalf of the city. It has no resemblance to how negotiations are handled in the capital market.”

When the PawSox in 2017 indicated they were considering leaving their long-time home of Pawtucket, about 20 local governments from around New England offered various deals to bring the team to their communities. PawSox officials have said they chose Worcester because of its rising economic and cultural momentum, although the then $101 million in public financing Worcester offered the team was far more than the $38 million Rhode Island offered to keep the team in Pawtucket.

Ballpark deed is 19 months behind schedule

City officials chose to build the ballpark on the advice of a paid consultant, the sports economist Andrew Zimbalist from Smith College in Northampton, who typically had been a critic of publicly funded stadiums, including in his 1997 book.

However, Zimbalist advised Worcester would buck that trend, mostly because of a planned mixed-use development from Madison Properties, which originally expected to invest $140 million to build hotels, apartments, an office building and retail spaces. The money generated in taxes and fees from Madison’s development, along with parking revenue from the baseball games and the team’s annual $1-million lease payment, was supposed to offset the money the city would borrow to build the stadium.

Madison bought 18 acres of property on both sides of Madison Street from the manufacturing firm Wyman-Gordon in March 2019 for $6.1 million, including the site on which the ballpark sits. In exchange for tax breaks on the various buildings of its mixed-use development and the city waiving $2.25 million in permitting fees, Madison was supposed to convey the land for the ballpark to the city.

The original deadline for that deal was April 1, 2019.

Madison President Dowdle didn’t return messages seeking comment on why Madison has been delaying in giving the city the ballpark site. The current memorandum of understanding between Madison and the city is non-binding.

Madison bought the ballpark property first, instead of the city obtaining it directly, Bird said, because Madison and Wyman-Gordon were already in sale discussions.

Without a deed to the Polar Park site, the city has relied on a series of right-of-entry agreements with Madison in order to continue construction on the ballpark. Madison and the city have signed a number of extensions to the right-of-entry contracts, including in December, February, April, June and July. The latest extension lasts until the end of September.

The Worcester Redevelopment Authority approved the conveyance of the ballpark property to the city in its Sept. 25 meeting, with the land transfer expected to take place within 10 days.

Martin Greenberg, a professor at the Marquette University School of Law in Wisconsin and the managing member of a firm specializing in real estate and sports law deals, called the lack of completed agreements in Worcester unusual and concerning.

“This should be relatively simple. It’s a sale of a property to the city,” Greenberg said. “That is not difficult.”

“What he’s doing,” Greenberg said of Dowdle and the ballpark site, “is he’s attempted to leverage the public-purpose property for his development. What’s unfortunate about this is this should have all been worked out up front.”

“This is not usual,” he added, about Worcester’s situation.

COVID’s impact on the $125M surrounding development

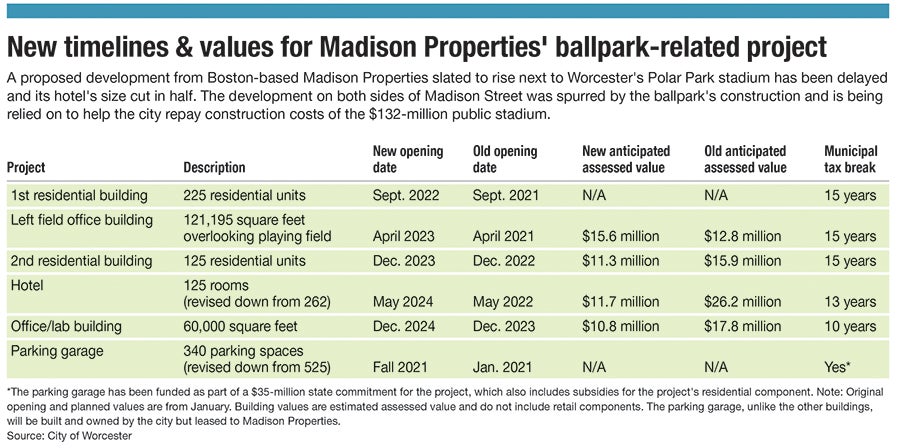

The latest proposal from Madison calls for 945,000 square feet of space, including 125 hotel rooms and 350 apartments, along with retail and office uses.

The developer has delayed the opening of each of the project’s components for one to two years, while cutting in half the number of planned hotel rooms.

The first building, originally slated to open early in 2021, will now open roughly a year and a half late. The project isn’t slated for total build-out until the end of 2024.

The value of the project has decreased, too, although Dowdle and the city declined to update the anticipated level of investment from Madison. In January, the city estimated the assessed value of four of Madison’s five buildings would be a combined $73.7 million; on Sept. 18, that anticipated assessed value was changed to $49.3 million.

The coronavirus pandemic has adversely impacted the industries slated to go into the Madison development, as brick-and-mortar retailers and restaurants are laying off workers, and the demand for office space has become unpredictable as employers keep workers home. The hotel market has softened dramatically. Average revenue per room nationally during the pandemic has fallen 80%, according to the realty market firm Colliers. The hotel market firm STR has predicted the industry won’t return to its 2019 levels until 2023.

Because of this, Daniel Etna, the co-chair of the sports law group at the New York firm Herrick Feinstein, speculated Madison could be using the deed transaction as leverage to make the mixed-use project more viable.

“Perhaps the developer’s going to be able to get some sort of benefits” because the city needs a sale transaction to take place, said Etna. “The developer’s end game is not to sit there with an undeveloped project.”

The development has site plan approval for the first residential building, but construction work has yet to begin.

“The medium term looks terrible for the deal,” said Victor Matheson, a sports economist at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, who has closely followed the project and is among the most prominent voices in the industry.

“No way a developer goes ahead with a major hotel, restaurant or retail development, all of which are part of the [tax break deal],” Matheson said, citing economic conditions.