When Worcester child care advocacy nonprofit Edward Street received a $75,000 grant, it was an example of essential funding for early childhood organizations, which rely on foundational funding in the absence of adequate federal funding.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

At the end of January, the Worcester child care advocacy nonprofit Edward Street received a $75,000 grant as part of the Greater Worcester Community Foundation’s annual allocation to support the region’s nonprofits, of which 120 received funding this year.

The allocation to Edward Street was the third largest grant in the $2.2 million GWCF gave out this year and represented 20% of the nonprofit’s annual revenue. This funding is essential to Edward Street, which serves as an example of early childhood organizations' reliance on foundational funding in the absence of adequate federal funding in a difficult economic model.

“Without state and federal investment, the early childhood system will not make it. It will fail in the next few years,” said Eve Gilmore, CEO of Edward Street, an early childhood advocacy and workforce development organization that has positioned itself to spur federal intervention into a precarious early childhood system.

The grant from the GWCF gives Edward Street $75,000 over two payments. Edward Street reported $374,823 in revenue in 2020, of which $76,111 was from government grants, according to the nonprofit financial tracking service GuideStar. Edward Street’s expenses for that year were $464,673, the most recent data available.

The entire child care system is in crisis, as rising costs are creating a burden on families while the low pay in the industry is keeping potential workers away. Edward Street’s overreliance on foundation funding is illustrative of the tenuous financial position the industry occupies, as efforts to fund child care through government intervention are still in the early stages.

Three crises

The early childhood system is struggling, based on overlapping factors impacting individual families and big businesses alike. Three concurring crises are tearing the system apart, said Andrew Farnitano, communications consultant at the Common Start Coalition. Started in 2018, the coalition is made up of 150 organizations across the state as well as independent members advocating for access to affordable, high-quality early education and child care in Massachusetts.

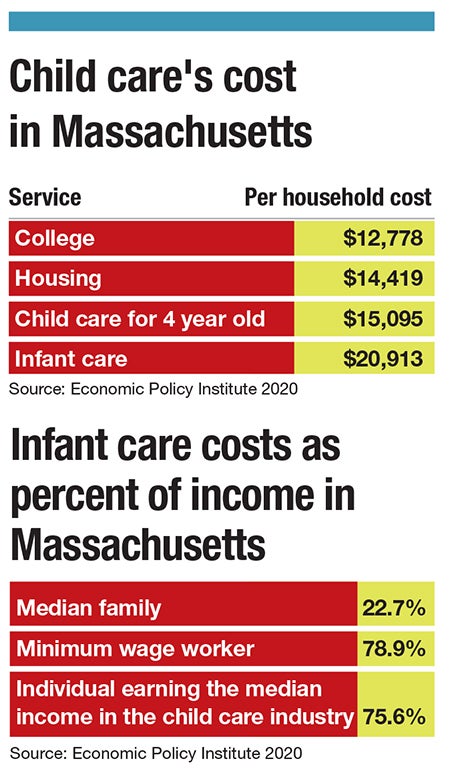

Issue one is the affordability of child care in Massachusetts, said Farnitano. Costs here are some of the highest in the nation; Massachusetts is ranked as the second most expensive state for child care by the left-leaning think tank Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C. The average annual cost of child care for a 4 year old costs $15,095; infant care is $20,913, according to EPI.

The second issue is low pay for educators, who are finding the work they are passionate about does not make a sustainable career.

“You see many people who love working in the field leaving to work in public schools, or even in retail,” he said. “They’re finding they can make more money working for Amazon or Dunkin’ Donuts.”

Issues one and two are seemingly at odds with each other; if pay increases, costs for families in the form of tuition will increase. This is why the coalition is pushing for federal funding.

They aren’t alone. Nationally, there has been a push to examine childcare costs, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) introduced on Feb. 9 new legislation to limit costs for childcare to $10 a day in some cases. The bill, in the very initial stages of its legislative journey, would utilize a sliding scale based on family income. Warren’s bill comes in the wake of the failure of President Joe Biden to pass his Build Back Better legislative agenda, which included significant subsidies and tax credits for child care but was dropped in 2022 in favor of slimmer economic legislation.

The third issue, said Farnitano, is the availability of care, which is tied to pay for educators.

“Centers have enough physical space, but not enough educators for their capacity,” he said.

As a result, many child care centers are sparsely filled, even as parents are seeking options for their children.

“The numbers just don't add up,” Farnitano said.

A drag on the economy

Edward Street is working to increase community awareness of the importance of investment in high-quality early education and care and raise the concern for the issue broadly. The organization takes a two-pronged approach to addressing the overarching problems, both through advocacy and resource development in the form of its Master Teacher Project.

The master teacher program is Edward Street’s tangible work on the ground. Its goal is to elevate the experience and skills of educators in early childhood centers in the area, which service most high-risk students. This is done through teacher-to-teacher training, in which an experienced teacher observes a classroom and has one-on-one and team meetings with the classroom teacher. The program provides hands-on training to elevate the expertise of the classroom teacher and enrich the educational experience for the children served to keep high-quality teachers in front of young children.

Its advocacy work, too, is centered around the pipeline of educators entering the field of early childhood. The poor wages for early childhood educators represent an equity issue, considering the demographics of the workers. Nationally, 97% of early childhood educators are women, and 38% are women of color, according to a 2022 report from the Center for American Progress, an independent, nonpartisan policy institute based in Washington, D.C.

The problems in the child care industry contribute to gender inequalities, as more and more parents, specifically mothers, are leaving the workforce to avoid costly child care, according to CAP. The results are felt by employers in addition to individuals.

“The system is broken for educators and broken for employers, who are losing billions of dollars because of employees leaving jobs due to worries about care,” said Gilmore. “A lot of the work we do is bringing the right people around the table to develop the issues facing early childhood.”

This issue is only just coming to the forefront of the minds of employers and funders, said Gilmore. Raising the profile of the issue is a large but not insurmountable step for early childhood organizations.

Corporations are finally recognizing what early childhood advocates have known for years, said Farantino.

“These issues are holding back the whole economy,” he said.

A gift to the Worcester community

Edward Street received the third largest grant from the GWCF in its January funding round. The nonprofit was chosen because of its track record in hands-on work and legislative efforts, said Jonathan Cohen, vice president for programs and strategy at the foundation.

“They are raising the bar across the board,” he said. “In Worcester in particular, it's a gift to this community that they exist and are doing the work that they are.”

The foundation recognizes the precarious place early childhood has in the public view and as a result has put an emphasis on providing funding for early childhood education organizations.

“The foundation over the last few years, even before pandemic, we had prioritized early childhood,” said Cohen, acknowledging the issues existed before the pandemic drastically altered the landscape for at-home child care.

Getting funding is becoming increasingly challenging as more organizations vie for the limited funds. The 2022 grant cycle was one of the most competitive in the GWCF’s history, said Cohen.

“There’s more need than ever before,” he said. “It’s not unexpected, but there is tremendous demand and supply hovers around the same number.”

In previous years, GWCF gave Edward Street funding mostly for the master teacher program, but now the larger portion is for operational support. This was an intentional shift, said Cohen. General operational support means they don't have to contort to a funder to fulfill a specific project, he said.

“It’s a recognition that they are doing important, meaningful work,” said Cohen. “They are the experts of what the need is in the community.”

For Edward Street, the funding helps a small organization of five employees sustain their work. Gilmore sits on a City of Worcester governance council focused on early childhood education, which is overseeing the work the City is doing to develop its platform and commitment to families and children.

“There is tremendous work that has occurred around the broken economic model of early education,” said Gilmore. “There’s more to do.”