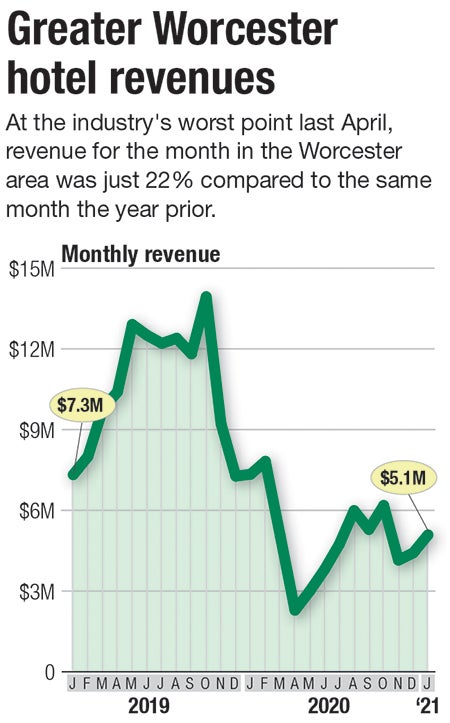

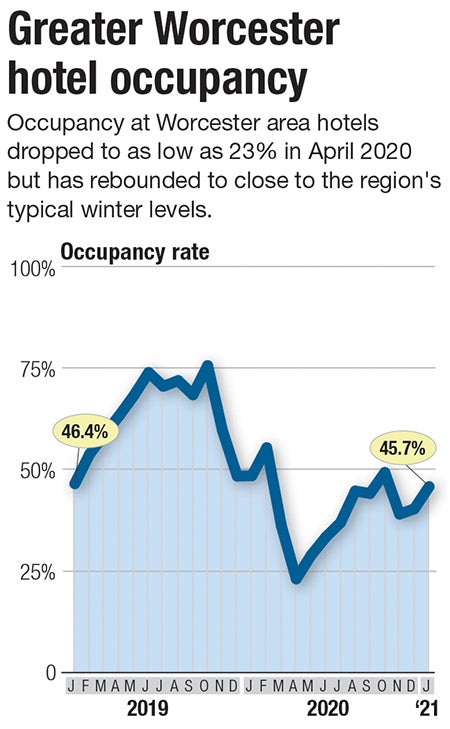

The Worcester metro area benefits in part by relying less on tourism or major conventions, two areas crippled during the pandemic. That’s helped it exceed national hotel occupancy averages, even as numbers have declined sharply locally.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Assaad Hallak has noticed something unexpected at the Homewood Suites hotel in Worcester, where he’s the general manager. The hotel on Washington Square has been busier this winter than it was last year before the coronavirus pandemic hit.

“It was very surprising to me, to be honest, but thank God,” Hallak said.

That stretch of success for the Homewood Suites, stretching from December through mid-March, which is typically the Worcester area’s slow season for hotel business, illustrates a relatively bright spot amid the pandemic: The area’s hotel industry is not only improving since the pandemic hit but exceeding national averages.

The Worcester metropolitan area's occupancy rate in January was 45.7%, compared to a national average of 39.3%, according to STR, a global hospitality data and analytics company. It was also not so significantly below the rate a year prior: 48.4%.

The Worcester metro area, which includes Worcester County and Connecticut's Windham County, benefits in part by relying less on tourism or major conventions, two areas crippled during the pandemic. Among the country's largest markets, for example, Oahu, which includes Honolulu in Hawaii, had a January occupancy rate of 23.6%.

January, despite normally being the area's slowest month for hotels, was among the best since the pandemic hit, even as the region hit all-time highs in new cases. The worst month was last April, during the region's initial spike in cases, when occupancy hit 22.9%.

“They fared well during the pandemic relative to other regions, but compared to where they were last year, they were significantly down,” said Monique Messier, the executive director of the tourism agency Discover Central Massachusetts.

Not all the area’s hotels stayed open throughout the pandemic, and at least some remain closed, including the region’s largest, the 406-room Great Wolf Lodge in Fitchburg, and the DoubleTree in Westborough. Both will open April 1.

Others have suffered major – at least temporarily – job losses, including Worcester’s AC Hotel, which had 15 employees, according to the city, compared to 90 when it opened in 2018. The Hilton Garden Inn downtown was down to 22, compared to 100 normally, and the Hampton Inn was down to five because it is being used temporarily as a dormitory by Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

Surviving the past year

Hotels adjusted to the pandemic much the same way similar businesses relying on guests such as restaurants did: with plexiglass, hand sanitizer stations, signs for reminders about proper distancing, and extra cleaning.

Initially, hotels were keeping rooms empty for 72 hours between guests, a time shortened as the pandemic has moved along. Other restrictions are still generally in place, including no visitors of guests or guests having to affirm doing online reservations that they’re in compliance with health protocols. Pools and fitness centers are typically off-limits.

For the 160-room AC Hotel, the hotel had to operate to the standards of its parent Marriott brand, something that General Manager Mary Simone said was reassuring to guests. No one could enter the building without a key, and the hotel’s connection to the adjacent 110 Grill, normally an easy walk through a doorway, was locked.

“We have to know who’s walking in our building,” Simone said.

Easy highway access and proximity to two busy hospitals, Saint Vincent Hospital and UMass Memorial Medical Center, plus a field hospital at the DCU Center helped, Simone said. That showed Worcester was a safe city for the pandemic, with important services nearby, she said.

At the Homewood Suites, the typical self-serve breakfast has been replaced by an arrangement in which hotel workers take requests and serve guests food.

After each room is cleaned between guests, a Lysol-branded seal is placed over the doorway, assuring guests no one else has been inside except for the cleaning staff.

Challenging a growing market

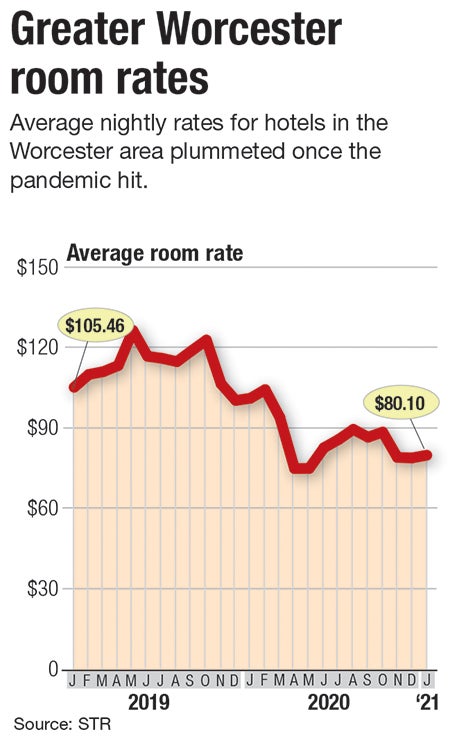

Hotel industry experts aren’t predicting a quick return to pre-pandemic levels. Average daily room rates, for example, fell 21% in 2020, and are forecasted to rise by 5% this year, CoStar analyst Jan Freitag wrote in December.

CoStar doesn’t project room rates to hit pre-pandemic levels again until at least 2024. That’s expected to crimp the number of new hotels coming online.

The pandemic-related downturn comes as the growth of the Worcester area’s hotel industry takes at least a short pause following three hotel openings from 2016 to 2019.

Two have been delayed, including a planned roughly 100-room Home2 Suites across from the Homewood Suites, to be built by the same developer, Fall River-based First Bristol. Work is now slated to start within the next year.

A hotel planned for across the street from the Polar Park baseball stadium on Madison Street has been pushed back to a May 2024 opening, and reduced in size from 262 units split between two brands to a single, 125-room development.

One area is expected to bounce back earlier: weddings and other family events whose emotional pulls are harder to postpone. Corporate events aren’t expected to take place as soon.

“Those numbers definitely hurt the region last year, and that’s what we need to make up,” Messier said.

Discover Central Massachusetts has been active on social media to keep the region in people’s minds as they look to make post-pandemic plans, with recent posts of wintery photos, celebrating Wormtown Brewery’s new taproom in Worcester, or the planned reopening of Armsby Abbey on Main Street, among plenty of others. The tourism agency posted tips on weddings in 2021, including downsized or outdoor ceremonies.

There’s optimism for the rest of the year, with vaccinations rolling out quickly and people having pent-up demand to get out and travel, see family or feel a sense of normalcy again. Discover Central Massachusetts saw thousands of new social media followers during the pandemic, a sign, Messier said, people are eager for information on the area.

The AC Hotel has begun seeing more regular guests again, Simone said. Hallak didn’t make any predictions but said homebound pandemic life has grown old for many.

“People are tired,” he said. “They want to get out and travel.”