Quietly, while Massachusetts health priorities have been focused on opioids and vaping, an outbreak has led to hundreds of hospitalizations and spurred health officials to alert the public to use more precautions.

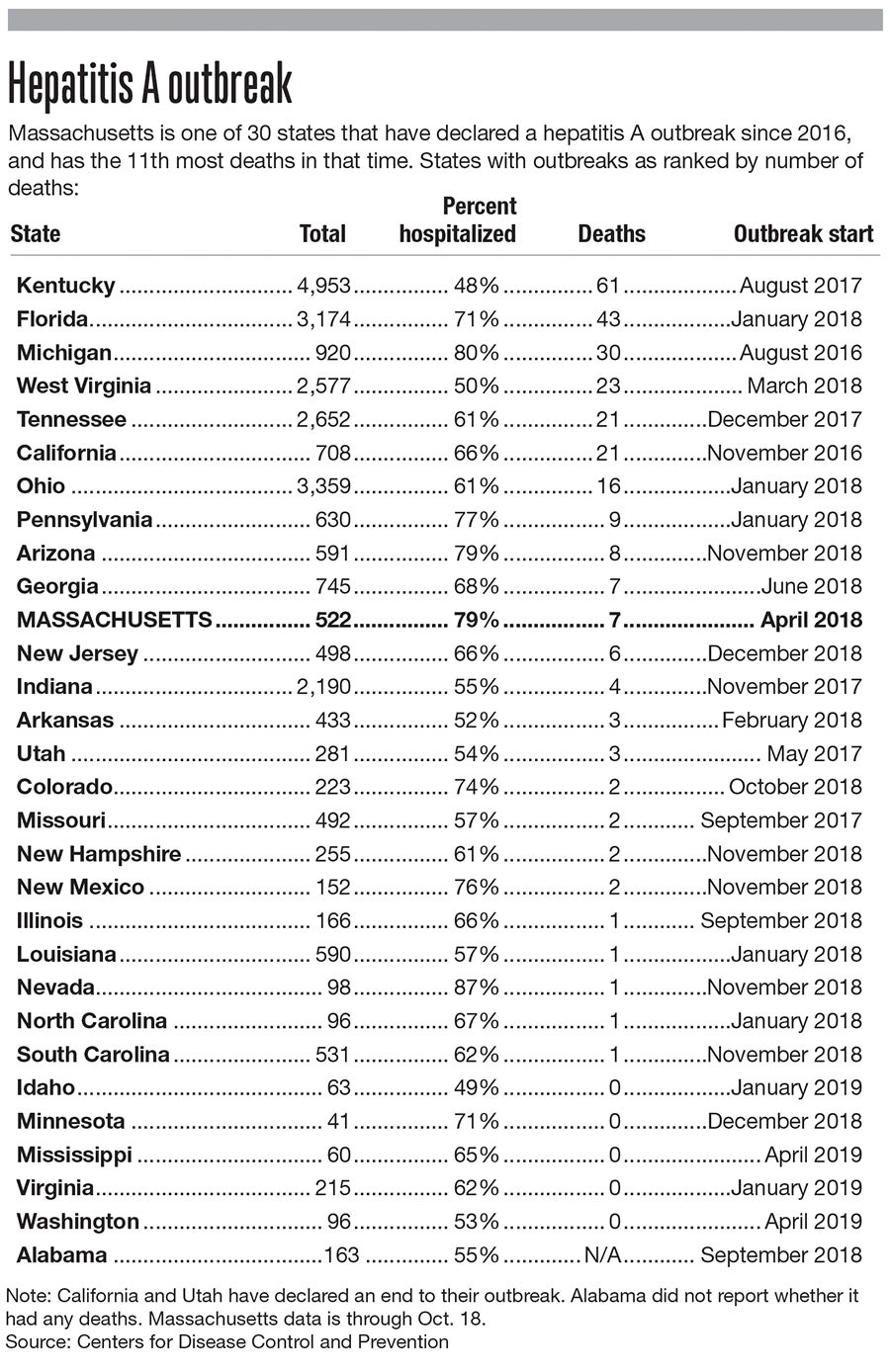

Seven Massachusetts residents have been killed in a hepatitis A outbreak started a year and a half ago, with more than 500 people infected. Four out of five who’ve been affected have been hospitalized.

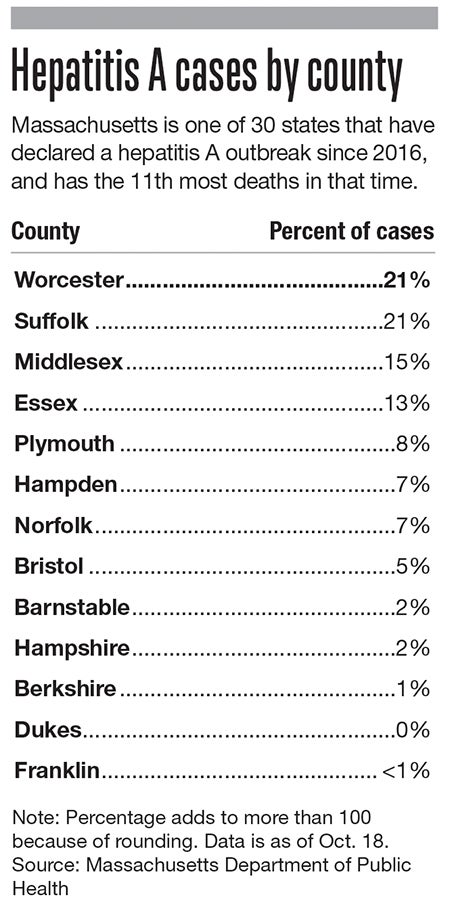

Of 522 cases confirmed by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health since the start of 2018, 21%, or more than 100, have taken place in Worcester County, tying Suffolk County for the highest incidence rate in the state.

More than 60 have been reported in Worcester alone, leading health officials with the city, as well as counterparts at health agencies and hospitals, to set out on vaccination drives among at-risk populations: the homeless and those fighting substance abuse.

“It’s truly a public health issue that we’ve had,” said Dr. Matilde Castiel, Worcester’s health commissioner. “And it’s not just us, it’s across the country.”

Massachusetts is tied for 10th most deaths in the country among the current spate of hepatitis A outbreaks across the country that has hit 30 states, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. Nationwide, 275 have died since 2016, and more than 27,000 have been affected.

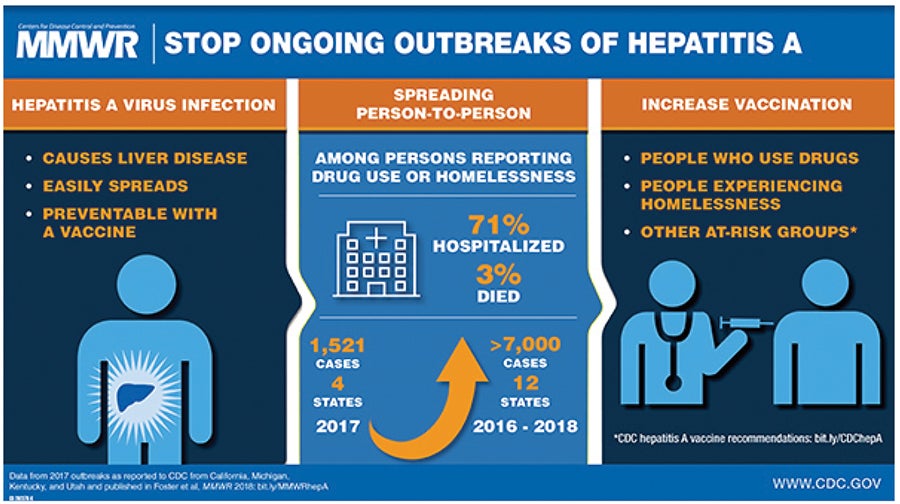

The disease is spread through sex, drug use, and by contaminated food or water, a risk made greater by not washing hands after using the restroom. The virus can survive on surfaces for several months, making it easier to catch, and the CDC says it is very contagious, with the potential for people to spread it before seeing any symptoms themselves.

Nearly half of those who’ve caught hepatitis A in Massachusetts also have hepatitis C, a similar viral infection of the liver spreading through contaminated blood. A third are homeless or have unstable housing situations, more than half have known injection drug use, and more than two-thirds have a known illicit drug use.

An unexpected outbreak

The national outbreak of hepatitis A hit after years of very few cases.

Numbers peaked in the 1970s with more than 60,000 occurrences, according to the CDC. Rates plummeted roughly 95% after the CDC recommended in 1996 vaccinations for those most at-risk, including international travelers, men who have sex with men, drug users, and children living in communities with high rates of disease.

In 2006, the agency expanded recommendations to include routine vaccination for children at age 1, and rates fell lower.

Rates fell to only a few thousand a year but have since spiked to the highest level since around when those vaccines were first licensed in the 1990s. Numbers started jumping in 2006 and have remained high.

“We were all taken by surprise by this, to be honest,” said Dr. George Abraham, the associate chief of medicine at Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester.

In Massachusetts, the typical rate until this outbreak would have been about one case a week across the state, or about 50 per year, said Kevin Cranston, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health’s assistant commissioner and director of its Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Sciences.

Hepatitis A cases started rising early in 2018 and then spiked in the middle of last year, Cranston said.

An aggressive response

Worcester, with a sizeable homeless community and dozens of opioid deaths each year, among other drug use, has been disproportionately hit by the outbreak.

The city has accounted for roughly 12% of the state’s hepatitis A cases, despite having less than 3% of the state’s residents.

The response has included the city’s health office, hospitals and other health providers including the Edward M. Kennedy Community Health Center and the Family Health Center of Worcester vaccinating at-risk residents and spreading word of the importance of hand-washing after using the restroom and before eating.

The city’s health office has given 533 vaccinations since June 2018, largely at homeless shelters and human service agencies where they may be most likely to be found, Castiel said. The city started reaching out to hospitals and treatment centers to start the vaccination process after officials heard an outbreak was underway in Boston, she said.

The Family Health Center is working on electronic health record reports to idenify any remaining at-risk individuals for any needed follow-up, and is continuing to screen patients in its substance abuse treatment program.

Abraham estimates a peak in cases locally around six months ago, helped by both vaccinations and an awareness campaign.

“We’re trying to break the cycle, and I think we’ve had some success,” Abraham said.

Nationally, the CDC spent roughly $9.1 million in fiscal 2018 for nearly 160,000 vaccines. In Massachusetts, the Department of Public Health has distributed 14,770 doses of vaccines in an attempt to break the outbreak under control.

They haven’t gotten there quite yet.

“We’re still seeing three or four cases a week, so we still haven’t gotten to the end of this,” Cranston said.

One silver lining in the outbreak: hepatitis A is curable, and there’s a vaccine that’s easy to obtain.

Symptoms include yellow eyes and skin, fever, and an upset stomach and diarrhea, and someone with the virus may feel sick for up to a few months. Most recover and don’t have lasting liver damage, according to the CDC, but more than half of those affected nationally have been hospitalized.

The Department of Public Health recommends anyone who thinks they may have hepatitis A to go to a doctor or the hospital right away, especially if they drink alcohol or already have a liver disease like hepatitis C.