The most significant burden on the single-family market, not just in Central Massachusetts but around the country, is interest rates.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Over the second half of 2023, Lee Joseph, a Worcester real estate agent and president of the Realtor’s Association of Central Massachusetts, noticed a shift in the single-family home market.

“Even if open houses were well attended, and even if there were a lot of showings on the property, the offers received were diminished,” she said.

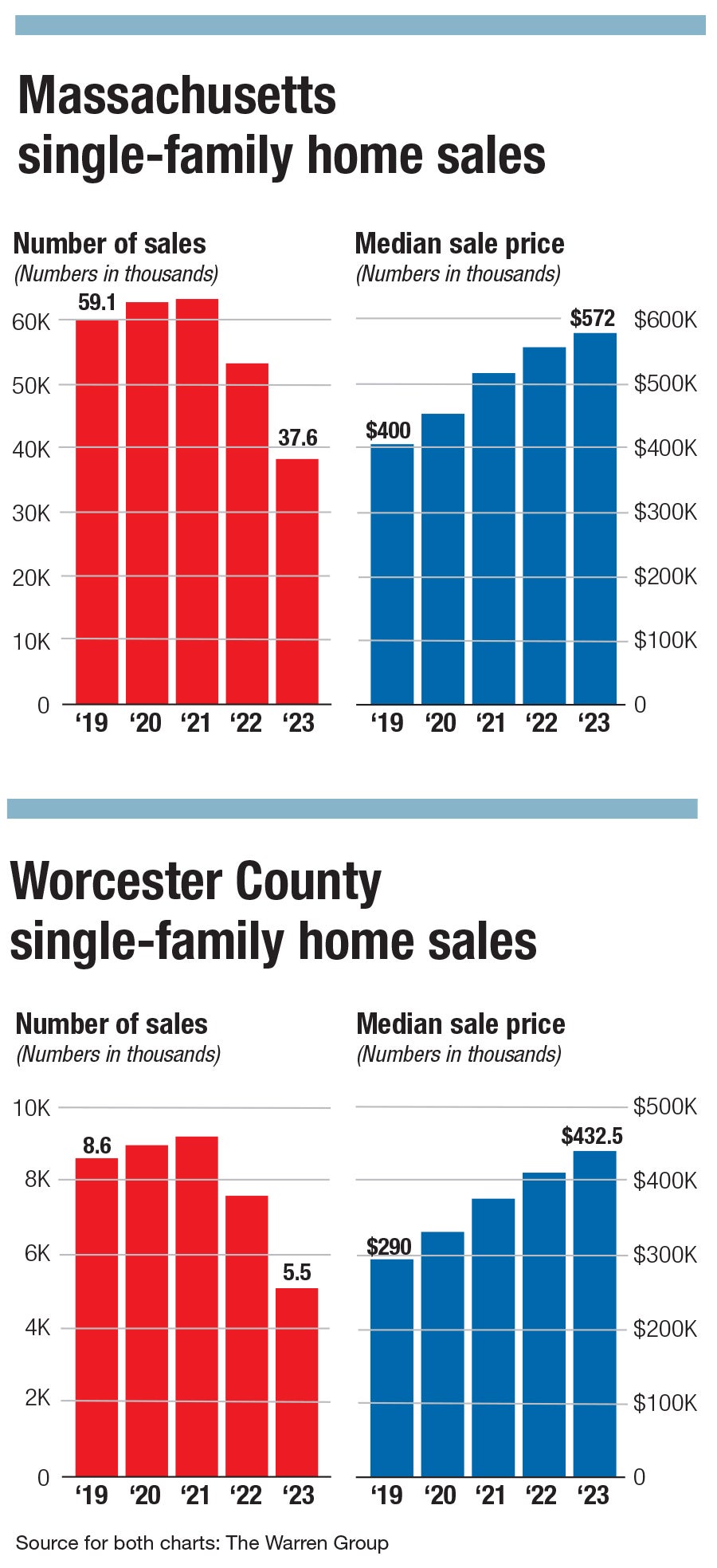

Housing has long been a sore spot in the economy of Central Massachusetts and the state as a whole, with high prices keeping home purchases out of reach for many people. Over the past two years, a combination of limited available stock and fast-rising mortgage interest rates has made the situation even worse. The good news, according to Joseph and others with an eye on home sales, is that state, local, and federal officials are pursuing policies to possibly improve things.

But we shouldn’t expect rapid improvement in the situation any time soon.

The most significant burden on the single-family market, not just in Central Massachusetts but around the country, is interest rates. After holding its rates way down since the start of the Great Recession in 2008, in 2022 the Federal Reserve started raising rates higher to combat inflation. And that, in turn, has driven interest rates on mortgages into the 6-8% range.

“People who have low-interest-rate loans now are reluctant to sell,” said Cassidy Norton, associate publisher and media relations director at The Warren Group, a Peabody-based real estate analytics firm.

With higher-interest-rate mortgages, a seller could move into a similar home but end up with much higher monthly mortgage payments, which gives homeowners an incentive to stay put, Norton said. Meanwhile, prices continue to rise, albeit not as rapidly as a couple years back, when year-over-year price increases were in double digits.

The Fed has signaled it plans to cut interest rates in 2024, but Norton said potential buyers shouldn’t expect a return to the rock-bottom rates.

“You’re still looking at interest rates that are so much higher than they used to be,” she said. “People are still going to have higher interest rates and more expensive housing.”

Limited supply

To really change the long-term prospects for single-family homes in the region, Norton and Joseph said, more homes will need to be built. That’s a tricky prospect since financing for construction is subject to daunting interest rates, and the costs of land and supplies continue to rise.

“I’m not seeing enough new construction,” Joseph said.

Another factor affecting the Central Massachusetts housing market is the continuing fallout from the shift to working from home begun with the COVID-19 pandemic. During the height of the pandemic, buyers made a rush to more rural parts of the state, including parts of Central Massachusetts, where homeowners would get homes with more space, Norton said, but it remains unclear how much that trend will continue.

“It’s still sort of up in the air whether people are going to go back to their offices,” she said.

The market is particularly difficult for would-be homebuyers from groups that traditionally have more difficulty, including first-time and first-generation buyers, as well as lower-income families and people of color.

“Disparities for Black families – and families of color – who tried to get into homeownership is pretty staggering for Massachusetts as a whole,” said David Sullivan, director of economic development and business recruitment at the Worcester Regional Chamber of Commerce.

These kinds of gaps become particularly glaring when interest rates rise, Joseph said. Young people from families with generational wealth can often get loans from parents and grandparents, allowing them to compete with buyers who can pay cash.

Making matters worse, federally funded pandemic-era programs designed to help first-time buyers have now run out of money, said Thomas Callahan, executive director of the Partnership for Financial Equity, a coalition of Massachusetts financial institutions and community groups.

Government-led efforts

The state’s housing woes are very much on the minds of government leaders at all levels, Sullivan said. Shortly after she was inaugurated into office, Gov. Maura Healey created the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities and selected former Worcester City Manager Edward Augustus to be the state’s first housing secretary, a cabinet-level position.

“The Healey-Driscoll administration has housing as its top priority,” Sullivan said.

In October, the Healey Administration presented a plan known as the Affordable Homes Act, with a goal of constructing 200,000 more units of housing by 2030.

If passed by the state legislature, it would provide $4 billion to construct and improve housing stock around the state and offer assistance to disadvantaged buyers. It includes a provision encouraging the construction of accessory dwelling units, small residential units sharing a lot with a single-family home.

Another important state-level change is the MBTA Communities Act, passed in 2021, which encourages the construction of more multifamily housing, Callahan said.

It requires Central Massachusetts communities served by commuter rail to adjust their zoning bylaws to permit more multi-family homes by the end of 2024.

Construction of more apartments and condos would have an indirect effect on the single-family market, although the measure has encountered resistance from communities. Most notably, Holden has faced a lawsuit and the ire of the Healey Administration for refusing to comply multifamily housing requirements in with the MBTA Communities Act.

“If some of these units are designed for seniors who are downsizing, that opens up the single-family homes they’re moving from,” Callahan said.

Since all these policy changes will take time to show results. In the meantime, would-be homebuyers may be destined to try their best in a market that’s stabilizing but still far from fixed.