An extended leave enables people to find their identities and focus on personal health, something they can not do in shorter chunks of time off, according to a lecturer at Harvard Business School.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

After nine years leading Worcester nonprofit support center Abby’s House as executive director, Stephanie Page left her position and pursued an independently funded year-long sabbatical.

During her time away, she stepped back and got distance from work to reflect, reconnect, and replenish herself, including by traveling internationally and developing healthier lifestyle practices. Page reflected and gained clarity and new perspectives on her work and life, she said. She took time to strengthen her relationships and spend time with friends, family, and people in her local community, as well as expanding her circle of connections through networking.

“I met a lot of new people, which was a really wonderful and sort of unexpected part of the sabbatical year,” she said.

Long seen as a practice limited to higher education, sabbaticals across all industries are becoming more common, as companies see the value in business executives taking time away from their jobs to focus on professional and personal development.

An extended leave enables people to find their identities and focus on personal health, something they can not do in shorter chunks of time off, said DJ DiDonna, lecturer at Harvard Business School in Boston and founder of the Sabbatical Project, a nonprofit conducting research on sabbaticals.

“Out of all the hundreds of people who [I have spoken to] that have taken a sabbatical, I have never heard anyone regret doing it,” DiDonna said.

Sabbaticals, on the rise

In January, 6.7% of employees nationally were on sabbatical, which is double the 2019 rate, according to data from Gusto, a California-based company providing payroll and human resource management to businesses. The data showed younger generations taking more sabbaticals, as 8% of workers aged 22 to 26 were on sabbatical, a stark contrast from the 1.7% in 2019.

Professionals in private, public, and nonprofit organizations across the U.S. who took sabbatical found significantly positive changes in their work-life balance, according to a study by the Harvard Business Review.

There are different types of sabbatical leaves, as some decide to return to their job, while others change career paths. Some sabbatical leaves are paid for by companies, while others privately fund their sabbaticals.

During her sabbatical, Page traveled abroad to Italy and Ireland, which she said exposed her to new cultures and ideas while visiting family. In addition, she rested and solidified healthy lifestyle practices, such as personal training, yoga, and meditation.

“As part of replenishment, I had time to really organize my personal life in ways that I hadn't had time for,” she said.

Following a sabbatical, some people may decide to go in a different direction for their careers, but for Page it affirmed her career interests in nonprofit and public leadership, which she intends to return to after her sabbatical, although she will not return to Abby’s House.

“It renewed my confidence in my leadership, and really has given me more focus and energy to return to work with. I also want to say that my plan is to continue the healthy lifestyle practices that I solidified during my sabbatical, and also use that to better support the well being and health of other people in the workplace,” Page said.

Impact on businesses

While sabbaticals were often only taken by those working in academia, an increasing number of non-educators are taking sabbaticals.

An extended break from one's job has become more appealing to employees, and the number of employers offering sabbaticals has grown, said DiDonna.

Regardless of sabbaticals, one of the only constants in business is people will leave companies, DiDonna said. A sabbatical gives an organization the opportunity to practice transferring job responsibilities and understanding what people want in their careers, which all businesses need to prioritize, he said.

When people take sabbaticals offered by their companies, 80% of people return to their job, according to DiDonna’s research.

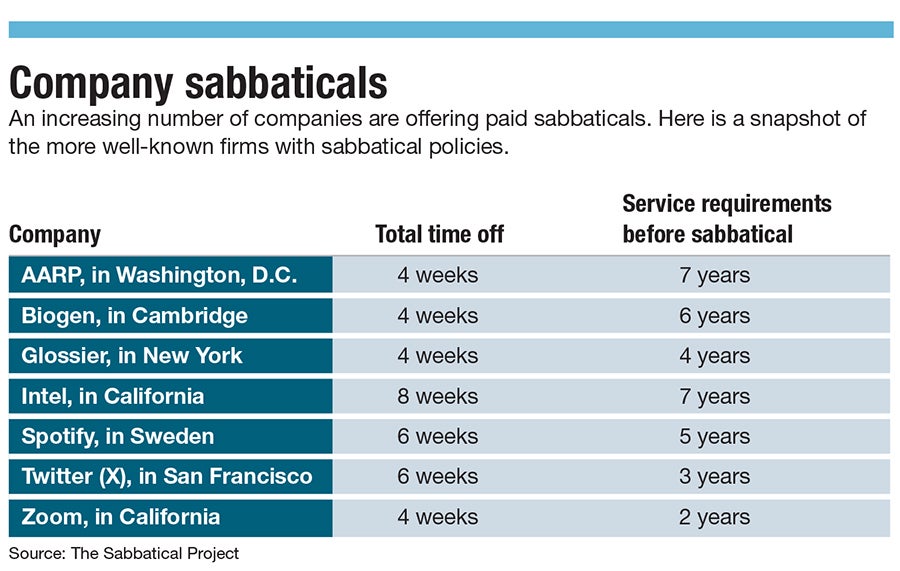

Approximately 5% of employers offer paid sabbaticals, while 11% of employers offer unpaid sabbaticals, according to a 2019 survey from the Society of Human Resource Management. Since then, COVID-19 played a significant role in the rise of sabbaticals, as people were able to experience time away from their routines and spend more time with family, DiDonna said.

Leading organizations through the pandemic was exhausting, but coming out of it, sabbaticals offer a chance for people to reset, Page said.

“We know people have made many different choices after the pandemic that they didn’t make before,” Page said.

Employees have put an emphasis on their mental health, following the COVID-19 pandemic, and in turn companies are seeing an increase in the frequency of workers taking time away from work to promote better work-life balance, according to data from Gusto.

Sabbaticals and social movements

Organizations have begun incorporating sabbaticals to strengthen their missions, such as the Black Mass Coalition in Boston.

The Black Mass Coalition created a sabbatical program for executive leaders who identify as Black or Indigenous and who lead social justice organizations rooted in Black, Indigenous or people of color (BIPOC) communities in Massachusetts.

The sabbatical program, funded by the coalition’s Black and Indigenous Resistance Fund, began in 2023 and will support four Black and Indigenous leaders this year, said Jason Boyd, executive director of the Black Mass Coalition.

The program grants the host organization $25,000 to support salary and other organizational needs for the duration of the three-month sabbatical, Boyd said.

Executives must have served in a leadership role in their organization for a minimum of three years to be considered for the sabbatical and a minimum of 51% of the individual’s organization must identify in BIPOC communities, according to the Black Mass Coalition website.

“It's not just folks who have been in it for 20 years. A sabbatical makes sense for people on various timelines of their career paths and social justice journey,” he said.

Boyd, who has been the director of the Black Mass Coalition since 2022, said he has not taken a sabbatical but understands the need for it.

“It's a way to have good people doing great work. It's a way to avoid burnout as well, and that's what's important to have in the social justice space in particular, for it to be sustainable, so that we don't lose that knowledge base, that experience, that skill set,” he said.

COVID-19 and the national movement centered around the Minneapolis police murder of George Floyd allowed others to consider the importance of social justice, he said.

“It offered an opportunity for individuals to rethink or be more intentional about self care, about honoring people who are doing important work and really moving towards a more equitable and sustainable way of doing business,” he said.

Organizations such as the BIPOC ED Coalition in Washington state and Nexus Community Partner’s ROOT Continuous Sabbatical Fellowship in Minnesota have similar opportunities for Black and Indigenous leaders.

A sabbatical community

After taking his own sabbatical, DiDonna realized little research existed about non-educators taking sabbaticals and decided to partner with social science researchers to collect data on sabbatical experiences, ultimately starting the nonprofit Sabbatical Project in 2019.

“I wanted to take the results of this research and create a home so that people who branch in sabbaticals could find a kind of community around it, because it's a pretty lonely and isolating experience leaving this routine life and conception of work,” DiDonna said. “It's about sharing stories and kind of creating a community that people can turn to around sabbaticals.”

For those interested in taking a sabbatical, DiDonna recommends finding someone in your network who has taken one to learn about their experiences.

Make sure to take enough time off during the sabbatical, as people need up to six weeks to disengage from their work identity and routine, DiDonna said.

Sara Bedigian is a participant in the Editorial Internship Program at Worcester Business Journal. She is a rising junior at the University of Connecticut, where she studies journalism and political science. She will be the editor of the student-run newspaper The Daily Campus in the fall.