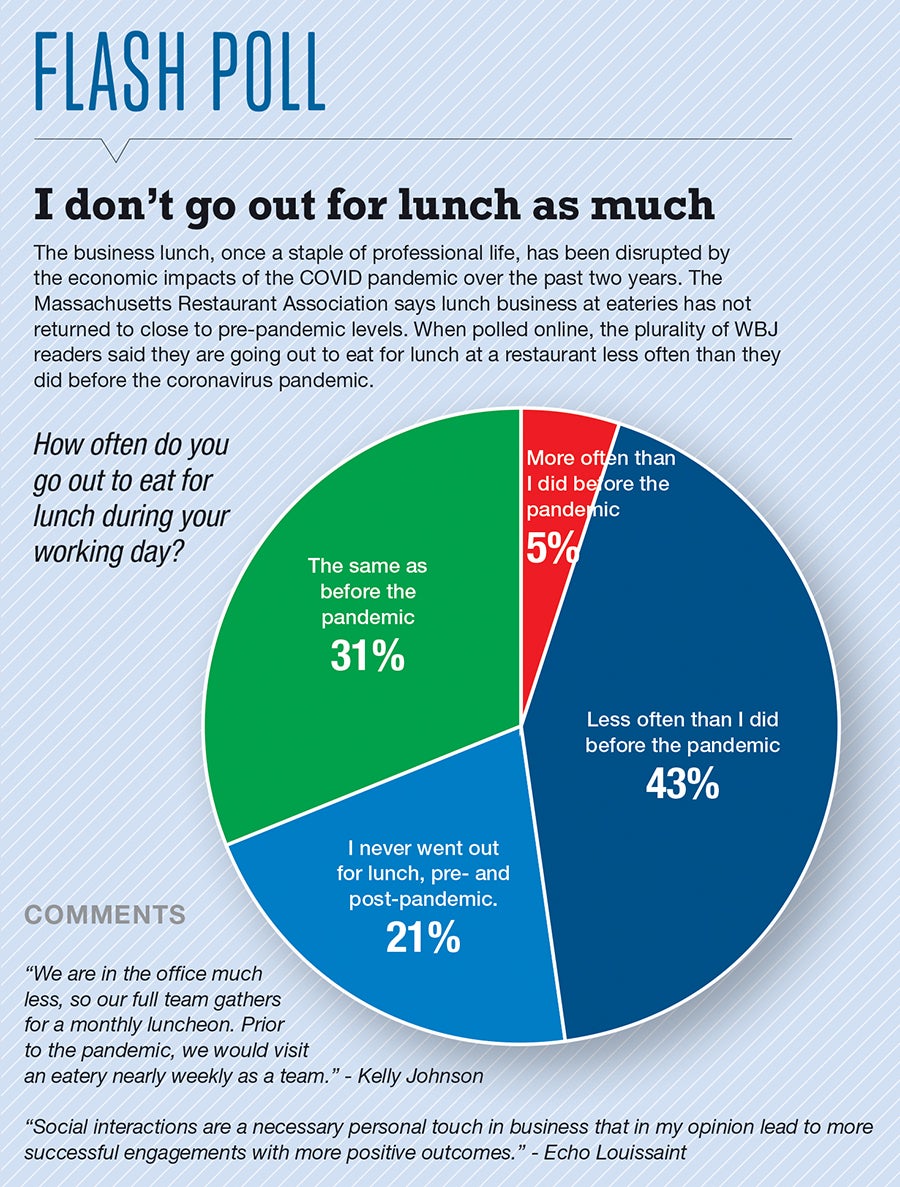

The workforce became decentralized, and fewer people went out for a quick lunch.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

With six months left on their lease for their downtown Worcester lunch restaurant, Jaime and Ryan Sens told their landlord they planned not to re-up. Z Cafe would close after 14 years. That’s what they did.

On Feb. 18, the Sens announced the end. They decided it was time to move on with their lives after two difficult years that almost broke them.

“We were losing money every month we stayed open since the day COVID started,” Jaime Sens said.

The Sens encountered issue after issue. Suppliers ran short of products and drivers, so they couldn’t deliver as often as usual, or even cut Z Cafe out entirely. The catering business Z Cafe relied on dried up as workers didn't return to offices for meetings. What went from a couple jobs daily dwindled to almost nothing. If workers weren't having meetings in the office, who were they going to cater for?

“In the last six months we were there, we probably did 20 catering jobs,” Ryan Sens said.

The workforce became decentralized, and fewer people went out for a quick lunch. Z Cafe made its money on people coming in for a quick lunch. They had banker's hours and fed the bankers nearby. They knew some customers for years whose meals they could prep before they ordered. But the clientele dried up with COVID, and fewer people were spending hours at the office.

On top of that, plenty of people learned to cook while stuck in their homes for eight months during the pandemic. There’s the regular customer Sens saw one day who apologized for not coming in anymore, but he’d learned to cook and now loved doing it and bringing lunch to work.

“If you pick a neighborhood or town and look around on different websites, [restaurants] aren’t open [for lunch],” said Steve Clark, president and CEO of Massachusetts Restaurant Association.

70,000 closures

A restaurant serving a sitdown lunch has become less prevalent since COVID. It’s lost its lure and its audience to last night’s leftovers.

The pandemic forced everyone to reexamine how they worked. No one has escaped the impact of COVID-19, but one of the industries most hit by the virus has been restaurants. When the lockdown began, we were told two weeks. It went longer. Restaurants stayed closed. They pivoted to new business models just to serve food. They became delivery services. They changed into markets. In September of 2020, WBZ News reported the Massachusetts Restaurant Association said around 3,600 restaurants closed for good. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the Washington Post estimates more than 70,000 restaurants nationally closed due to the pandemic and the ones that remain open, specifically independent restaurants, are deep in debt, barely hanging on, thanks to various government influxes of cash like the Restaurant Revitalization Fund and the Paycheck Protection Program

The Sens got money from both PPP loans and RRF. The loan paid for the few employees they had while the restaurant money kept them open for months and helped pay the back rent they owed from being closed for seven months the prior year. But it wasn’t enough. They were burned out, and the clientele never returned.

“We basically stayed open until the [grant] money [ran out]; and we burned through this, and we had x amount of dollars we were willing to lose,” Ryan Sens said.

Before the pandemic, catering kept Z Cafe afloat. Foot traffic in downtown Worcester hasn’t been strong for decades. When the restaurant deadhorse hill opened in April 2016, the hope was the large parking lots filled with commuters around the restaurant would allow it to do all-day business. Chef Jared Forman and his business partner Sean Woods set up a cafe counter for coffee. They opened early with breakfast and expected to stay open through dinner. But no one came. People preferred to make coffee at home or pick something up on the way to work, long before they parked their car and walked by the restaurant.

After cutting coffee, Forman wanted to keep lunch. Even as a self-professed lover of sandwiches, he soon noticed the drawbacks of trying to keep something alive that lacked stability. The decision was made to limit staff and work it the best they could, but every once in a while the restaurant would get slammed and the food suffered because one cook couldn’t handle it all. In the end, hiring a qualified and energetic staff to move with the ebbs and flows of the unpredictable schedule became too difficult and expensive.

“We were losing money when we cut it,” Forman said.

Forman and deadhorse called it quits on lunch before the pandemic, before the lunch crowd got even thinner. Even with limited service now, Forman is still looking to find a balance in the schedule that makes the most sense for his staff, his vision for what the restaurant can be, and what makes it financially viable.

Finding the right balance

Across the city, Michael Covino still has hope, though. As one of the owners of the Niche Hospitality Group in Worcester, he has seen a shift in the business of lunch. Niche’s concept The Fix Burger Bar lends itself to being a lunch restaurant because it focuses on burgers, a sandwich sitting neatly between pub fare and dinner. Plus, the Worcester location was once on Shrewsbury Street and then moved to the Northworks Building on Grove Street. It had a built-in audience in the area thanks to all the Worcester Polytechnic Institute buildings in Gateway Park and the proximity to other businesses on that side of the city. But now, Covino has noticed guests are less likely to come in for the impromptu lunch meals after a meeting, probably because we’re having less meetings in person these days.

“People have adjusted to doing business online,” Covino said.

The Fix’s other locations in Leominster and off of Simarano Drive in Marlborough made sense to be open for lunch. They’re centrally located near global office buildings. But, with more workers working remote or in hybrid positions, that audience has dwindled, Covino said. And it’s thrown a wrench into how restaurants operate and plan. Covino used to be able to look at the books for his restaurants and know pretty well how they’d perform throughout the year. COVID disrupted all of that. People got accustomed to take out, the convenience of delivery apps, and eating lunch at the office for efficiency.

“The pandemic changed people’s habits,” Covino said. “Things are habitual.”

While the likes of The Fix and deadhorse have adapted to takeout and what consumers want, they’ve also scaled back. They’ve begun to staff differently to make sure they don’t over-staff but not leave customers wondering what happened to one of their favorite places to eat because of poor service or food because of a shortage of workers to make the experience pop. With that, though, the feeling-out period of the new normal continues.

There’s “no crystal ball to see trends,” Covino said.

For now, the trends appear to be focused on outdoor dining, good takeout, and fewer restaurants open for business all day, so that they can stay open for years to come.

“How do you survive?” Clark said. “You have to be more efficient and sacrifice quantity, not quality.”