Hospital closure impact: As the final days for Nashoba Valley Medical Center ticked down, a community forsees a looming healthcare crisis

photo | EDD COTE

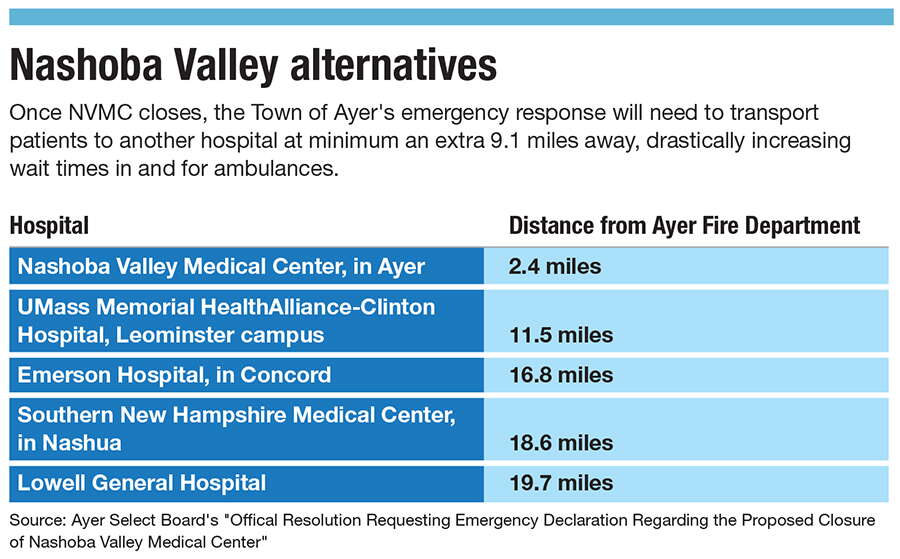

Audra Sprague, an emergency room nurse at Nashoba Valley Medical Center, stands with a cohort of her coworkers and supporters outside of the hospital ahead of its planned Aug. 31 closure.

photo | EDD COTE

Audra Sprague, an emergency room nurse at Nashoba Valley Medical Center, stands with a cohort of her coworkers and supporters outside of the hospital ahead of its planned Aug. 31 closure.

When Nashoba Valley Medical Center’s parent company, Texas-based Steward Health Care, filed for bankruptcy in May, providers at the Ayer hospital weren’t too concerned.

“Everybody truly was like ‘There's no way it can close,’ because this area wouldn't survive,” Audra Sprague, an emergency room nurse at the Nashoba Valley Medical Center for 17 years.

But then came July 26, and Steward announced it would close the 60-year-old Nashoba Valley, along with Carney Hospital in Dorchester, by Aug. 31, meaning the Nashoba Valley region’s sole hospital would close in just 36 days.

For this rural Massachusetts area, the hospital’s closure will mean extended ER wait times at neighboring hospitals already pushing capacity, quadrupled ambulance turnaround times, and ultimately, the potential collapse of a healthcare system already spread thin. Central Massachusetts’ largest hospital system – UMass Memorial Health in Worcester – has floated preliminary ideas to provide healthcare access in the region, but nothing would make up for the loss of the 77-bed hospital, which was staffed by 164 physicians and 430 nurses.

“There's impacts that people don't fully comprehend. I've been talking about this for two years: if Nashoba closes, or any other hospital in the state of Massachusetts, it's going to have a significant impact almost immediately that's going to ripple out,” said Brian Borneman, chief of the Pepperell Fire Department.

Steward Health Care officials declined to comment for this story. Nashoba Valley officially stopped accepting patients and closed on Aug. 31.

System strains

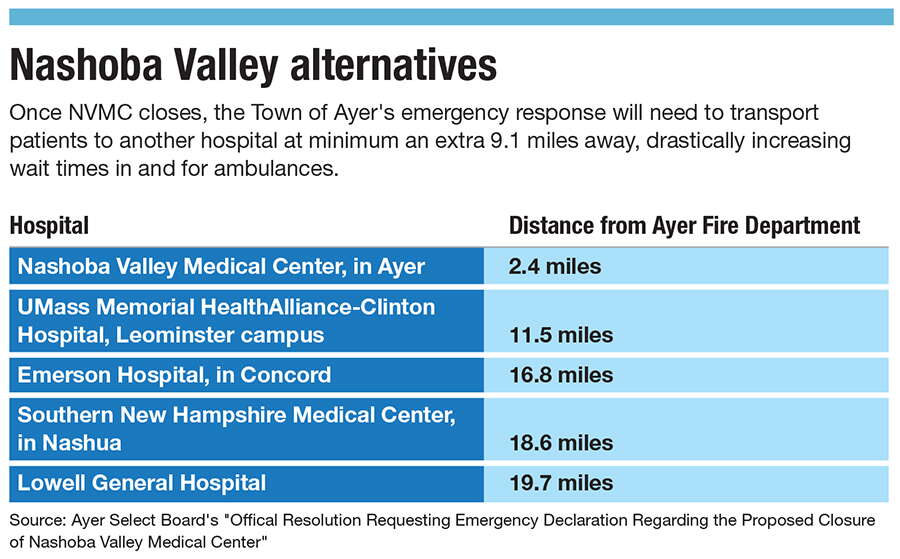

Serving the area’s 115,000 residents, Nashoba Valley receives approximately 16,000 annual emergency room visits and approximately 91,000 annual outpatient visits. With its imminent closure, residents will need to make it to the area’s next-closest hospitals, namely UMass Memorial HealthAlliance-Clinton Hospital’s Leominster campus and Emerson Hospital in Concord, locations 11.5 miles and 16.8 miles away from the Ayer Fire Department, respectively, as opposed to the 2.4-miles-away Nashoba Valley Medical Center.

But the Leominster and Concord hospitals don’t have a surplus of capacity, said Dr. Eric Dickson, president and CEO of UMass Memorial Health. In fact, he said HealthAlliance’s Leominster campus is one of the area’s most overwhelmed hospitals and twice as busy as Nashoba Valley.

Though UMass Memorial is working on contingency plans in an effort to prepare its neighboring hospitals for Nashoba Valley’s impending closure, Dickson said nothing will be at the scale of replacing what Nashoba Valley provides.

I haven’t “seen a plan yet that says, ‘Everything will be okay. It will function normally.’ Basically, we're going to do the best we can with what we have to work with,” he said.

If no other provider ends up taking over the hospital or another alternative for the facility isn't found, Dickson hopes UMass Memorial can work with the state to eventually utilize Nashoba Valley’s emergency room space and still provide some healthcare services for the region. Perhaps, it could turn it into an urgent care or a skilled nursing facility, but it’s not a short-term solution.

“This isn't going to be fixed in a day or two. This is going to have to be an intense recruitment effort to staff up and really then look at every area, every nook and cranny that we have to be able to take care of patients,” said Dickson. “The emergency departments will be busier. The waits to be seen will be longer. The hospital will be more crowded. But the real part of this that sometimes people fail to consider is what happens to the EMS system.”

EMS system challenges

The average Ayer ambulance turnaround time to and from Nashoba Valley is about 20 minutes, said Ayer Town Manager Robert Pontbriand. With Nashoba Valley closed, he said the average hospital turnaround time will grow to 60-90 minutes.

For residents of Pepperell, which is north of Ayer, wait times will be longer.

About 60% of Pepperell Fire Department transports go to Nashoba Valley and 90% of calls are turned around in about an hour, said chief Borneman. With the hospital’s closure, he anticipates turnaround times increasing 50%-100%.

Nashoba Valley could have made a difference in those emergency situations, said Sprague, the hospital’s ER nurse.

“Lives will be lost because seconds count,” said Sprague. “We're not a big medical mecca and a big trauma center, but where we're located, we can stabilize anything and get [patients] the immediate care they need.”

This increase in distance to health care won’t solely affect those utilizing the ER. Sprague foresees the distance most impacting seniors and those with chronic illnesses who frequent the hospital on a regular basis. With the distance to hospitals now doubling or tripling, Sprague said patients will postpone care.

“You think that everybody has a car or has somebody that can drive, and that's not the case in a lot of places. I mean, I've given patients rides home from the emergency room that came by ambulance because they had no ride and then they have no way to get home,” she said.

Alternative transportation options such as community shuttles or paying for Ubers are infeasible with the situation in which the town is headed, Pontbriand said. For example, the Ayer Council on Aging senior center brings senior residents to healthcare appointments via its one van holding 10 to 12 people, but when Nashoba Valley closes, he said it won’t be possible to bring everyone in need to their appointments. The extra expense that would come with paying for ride services might deter patients further from accessing care.

“Here is a traditional middle America, hard-working, traditional blue collar community. The people in these towns, they don't have all kinds of disposable income to begin with so increasing the distance is increasing their cost,” said Pontbriand.

The fear of patients postponing care is shared by Borneman and his peers. He said they foresee a similar situation to COVID when people delayed care because they were avoiding hospitals, but in this case, it will be because they lack an accessible hospital. In turn, Borneman said patients will be calling for an ambulance having developed acute conditions, but the availability of that ambulance may be up in the air.

“We still do firefighting. So if we're all tied up on ambulance calls and a fire comes in, in this area, we just don't have the staffing like bigger places and cities that can handle all this,” he said.

Service gaps

Massachusetts State Rep. Margaret Scarsdale (D-Pepperell) fears the services specifically provided by the region’s fire departments will be lost. While first responders are unavailable during longer turnaround times, she sees the potential for other vital aids to fall by the wayside.

“That means the services that our fire departments offer: inspection safety programs, fire prevention services, life safety education, those are all going to be in jeopardy because there'll be no one there to perform those services because they're sitting in traffic at the Concord Rotary,” said Scarsdale.

In addition, she said dispatch staff are going to have to learn to understand and navigate more complex scenarios regarding where to transport people amid higher demand for mutual aid within the Nashoba Valley.

Pepperell and surrounding towns have a robust mutual aid system, Borneman said, but if all towns are experiencing longer turnaround times, their collective ability to deliver an ambulance will diminish drastically.

As it is, Borneman’s department had to scramble to secure the use of Pepperell’s singular staffed ambulance since Steward announced Nashoba Valley’s closure. The Town needs an affiliation agreement with a hospital in order to operate an ambulance, and Pepperell would have been without a license had it not acquired a new agreement with Clinton Hospital’s Leominster campus.

State of uncertainty

Although there are plenty of known and predictable challenges ahead with Nashoba Valley’s closure, there are a number of unknown factors officials have expressed have the potential to further derail the region’s healthcare system.

Though the public health impact is of first and foremost concern for him, Pontbriand added Nashoba Valley’s closure may increase costs for towns to provide additional emergency services. With municipal budgets already set, the towns might not have the resources allocated to pay additional personnel, added fuel costs, or for a new ambulance, the last of which Ayer did to the tune of $400,000 with 18-month order lag, said Pontbriand.

Scarsdale is trying to identify pitfalls before they happen, such as what will happen to Nashoba Valley Medical Center’s helicopter landing zone used to transfer patients via helicopter.

“It's a whole region full of dominoes that are about to start falling, and the patient outcomes and the health of our towns are going to be severely impacted from that,” said Scarsdale.

Mica Kanner-Mascolo is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the healthcare and diversity, equity, and inclusion industries.

0 Comments