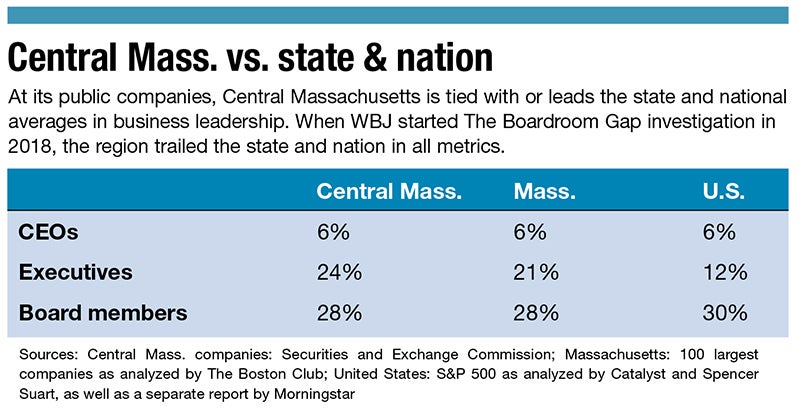

In its annual The Boardroom Gap investigation of gender diversity in the region’s business leadership, WBJ found 37% of executives & board members are women, unchanged from 2021.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Women make up nearly half of the U.S. workforce, yet their presence in leadership is still far smaller than men’s.

That disparity is just as pronounced in Central Massachusetts, even in female-dominated industries where the bottom and middle of the talent pipeline should have plenty of women candidates for leadership.

In its annual The Boardroom Gap investigation of gender diversity in the region’s business leadership, WBJ found 37% of executives and board members are women, a number unchanged from 2021. This is not just a low number for all industries studied, but it’s particularly unreflective of the female-majority workforces in industries like health care, hospitality, and education.

“It’s never been a level playing field,” said Natalie Rodriguez, owner and head chef of Nuestra restaurant in Worcester. “You have to have a strong voice and that determination, that backbone.”

The disproportionate number of women in the workforce compared to women in leadership reveals the many seen and unseen barriers to advancement women face, which not only limit women’s career prospects and earnings potential but also create a lack of diversity in company business leadership, ultimately hurting organizations’ profitability.

“When you have an informal pipeline of sorts to professional development opportunities, it’s going to lead into disparities of who ultimately moves through,” said Desiree Murphy, senior labor and employee relations specialist at UMass Memorial Health.

The Boardroom Gap findings

In 2021, women made up 47% of the U.S. workforce, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Women’s participation in the workforce has been impacted in the last two years by the coronavirus pandemic in a phenomenon known as The Shecession, where many women left their jobs to care for families or because they worked in frontline industries. The Mass. and Central Mass. workforces typically break down along similar lines as the nation, although updated figures aren’t available for 2021 or 2022.

To understand how the female workforce was being represented in leadership, WBJ determined genders of the 1,672 executives and board members who comprise the leadership at 75 prominent Central Massachusetts business organizations, in a continuation of The Boardroom Gap investigation started in 2018.

The investigation found women occupy 37% of the region’s business leadership positions, which ties the all-time high in the five-year study but is unchanged from last year. The percent of women leaders in the private corporations, colleges, and financial institutions studies all fell.

The Boardroom Gap did find some improvements from 2021. The number of companies with zero women in leadership dropped from eight to two, and the women in leadership at public companies jumped from 19% to 26%, led by new female board members.

Diversity in itself is valuable for a company. A 2019 study from McKinsey & Co. showed firms with more gender diverse executive teams were 25% more likely to experience above-average profitability, a figure which has risen incrementally from 15% in 2014.

In Central Massachusetts, WBJ found 11 of the companies studied had one woman in their leadership.

“When we have women who are solo in a team, this really makes it difficult for them,” said Laura Graves, a management professor at Clark University in Worcester. “They are much more likely to be harassed and much more likely to be stereotyped.”

These barriers contribute to pay disparities, keeping women out of higher-paying executive roles. While women make up a minority of leadership positions, they fill nearly two-thirds of all tipped positions in Massachusetts, according to a 2019 report from the National Women’s Law Center.

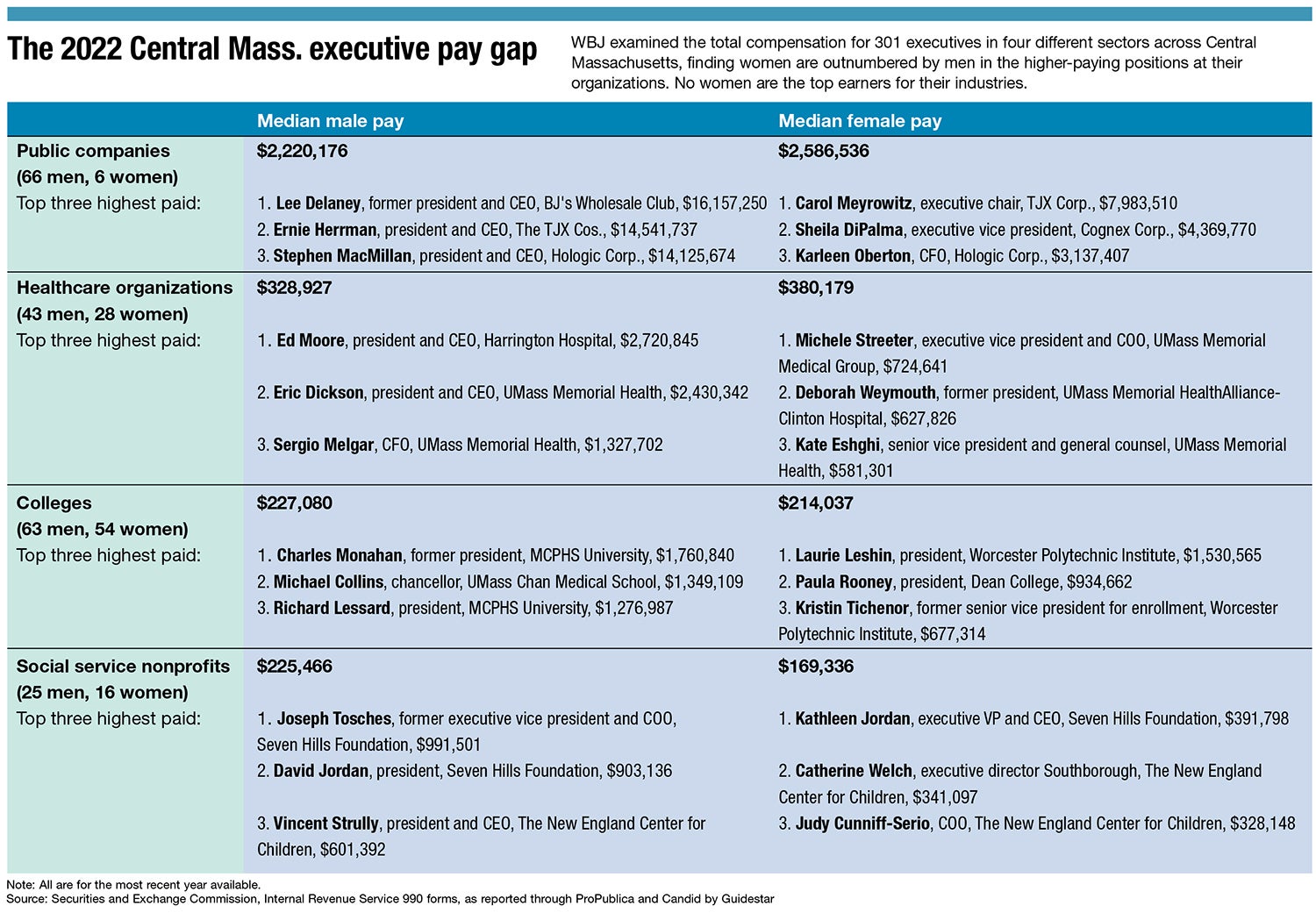

In The Boardroom Gap’s examination of 301 executives’ compensation in Central Massachusetts, WBJ found about a third of the region’s highest-paid executives are women. Even in sectors like education where there is almost an equal number of men and women in highest-paid positions, female executives make $13,043 less per year than their male counterparts.

Majority-female industries, led by men

Rodriguez, the owner of Nuestra, has worked in the hospitality industry since she was 16, but broke out on her own, after decades of toiling in an industry where most head chefs are men.

“If I didn’t have a strong personality and I didn’t have the confidence and posture that I have, I feel I would be chewed up and people would walk all over me,” she said.

While more than 68% of food industry servers are female, women make up only 23% of head chefs, according to BLS.

In Central Massachusetts, nonprofits, education, and healthcare have the highest rates of women in leadership, but – like the hospitality industry – the figures pale in comparison to the amount of female workers.

While 77% of Mass. healthcare workers are women, they only make up 38% of healthcare leadership in Central Massachusetts, according to The Boardroom Gap findings.

In higher education nationally, 60% of professionals are women, according to the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources. Yet, in Central Massachusetts, 40% of college executives and board of trustees members are women. Of the 15 colleges based in Central Massachusetts, three have female presidents, and two of those are leaving at the end of the spring semester.

Barriers, seen & unseen

Women face a number of barriers to advancement, ranging from biases at the workplace to increased childcare and household responsibilities.

Working doubly hard for respect is common among women trying to break into leadership roles, said Graves, the Clark professor. Women are frequently stereotyped within the workplace, and those gender biases become more prevalent when employees and employers are stratified by gender.

“As there is this distinction between who’s in the lower roles and who’s in the upper roles, then gender stereotypes are really going to come into play,” she said. “The fact that men are more represented at the top and women are represented in these lower-paid jobs exacerbates the likelihood that people are going to use their stereotypes.”

This becomes an issue especially in healthcare and education where women may be viewed as nurturing, but not necessarily competent or task-oriented, Graves said. Stereotypes impact influence, giving less power to women’s input.

“I feel like people just see women as more nurturing – and some of them are, some of them aren’t – but I feel like it’s just that natural thought that comes to people’s minds,” said Rodriguez. “It’s harder for us because we’re not as respected.”

Stereotyping can be extremely subtle, but it can go as far as to inform boards and hiring managers in their search for leaders, said Graves. At companies where men have traditionally been executives, it may be difficult to picture a woman holding that role.

“When the leader roles are associated with men, it really affects the ability of women to move up in the organization,” she said. “The image in people’s minds of the person in a managerial or leadership role is male, so women aren’t seen as a fit for the position.”

Because of this tendency, Graves emphasized the importance of creating a solid selection process focused on candidates’ knowledge, skills, and abilities to avoid the influence of such implicit biases.

Creating an inclusive environment for women goes beyond eliminating stereotypes, however. Organizational norms of overwork or constant physical presence are likely to exclude women, who typically have more household responsibilities than men. A Gallup study from 2020 showed the majority of women are more likely to rearrange their careers for children, and take on more childcare and household duties than their male partners.

“There’s a lot of aspects in the decision-making process that people go through in assessing whether or not to take the step forward in terms of moving up in the ranks,” said Murphy, from UMass Memorial.

Solution: Formalizing the advancement pipeline

UMass began a more calculated, system-wide effort to diversify its leadership after the murder of George Floyd, welcoming its first-ever chief diversity, equity, and inclusion officer, Brian Gibbs, in late 2020. So far, the DEI team has been in the research phase to understand pipelines and barriers to leadership advancement, said Murphy. She emphasized transparency will be key in bridging the divide between employees and employers.

Murphy hopes UMass’s work will create an executive team more reflective of the healthcare provider’s workforce, as well as its patient base.

When a company has an informal talent pipeline, candidates for promotion may be judged by perceived necessary qualifications, which may have nothing to do with their ability to succeed in leadership, said AiVi Nguyen, an employment attorney at Worcester law firm Bowditch & Dewey.

“It's just a matter of shifting what we value in our employees, shifting the characteristics we value or the diversity we value,” she said.

Many hiring processes and criteria are outdated and do not account for varying backgrounds, so formalizing and modernizing pipelines will be key for organizations to diversify leadership, Nguyen said.

“You just work backwards, like what do you need your employers to do well?” said Nguyen. “You take away all the weird markers that we've had in place forever, like that you didn't graduate top of your class. That doesn't tell you any of the actual qualities that you need in an employee at all.”