Systemic failures: A growing number of Mass. pregnancies are resulting in severe complications, the greatest impact falls on the Black community

IMAGE I Adobestock.com; AI Generated

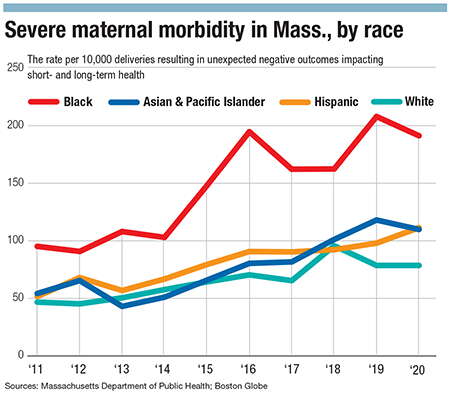

Rates of severe maternal morbidity in the state nearly doubled from 2011 to 2020, with Black birthing people among the most impacted by the unexpected negative outcomes of labor and delivery affecting short- and long-term health, according to a 2023 report from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

IMAGE I Adobestock.com; AI Generated

Rates of severe maternal morbidity in the state nearly doubled from 2011 to 2020, with Black birthing people among the most impacted by the unexpected negative outcomes of labor and delivery affecting short- and long-term health, according to a 2023 report from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Massachusetts is facing a mounting maternal morbidity crisis, the likes of which aren’t slowing down.

Rates of severe maternal morbidity in the state nearly doubled from 2011 to 2020, with Black birthing people among the most impacted by the unexpected negative outcomes of labor and delivery affecting short- and long-term health, according to a 2023 report from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

“When a pregnant person dies, it means that something is profoundly wrong with the healthcare system,” said Hafsatou Diop, DPH’s inaugural assistant commissioner of health equity. “No one should be dying because they’re pregnant, particularly in a rich country like the U.S., particularly Massachusetts, where you have the best hospitals in the whole world and the best of providers. That should not just happen.”

Mitigating this rising problem in Central Massachusetts will take a multifaceted approach. The healthcare system needs to diversify its workforce and implement training on implicit bias and racism, communities need to be more culturally competent and supportive of women throughout all stages of pregnancy and postpartum, and those in positions of power need to prioritize funding qualitative research on the real-life experiences of pregnant and birthing people.

“We recognize that racism is pervasive in society. It's in the water, it's in the air, it's woven through [the] health system, it's woven through education, housing, etc.,” said Dr. Cherise Hamblin, OB/GYN and medical director of the UMass Memorial Health doula program.

A systemic root cause

Part of recognizing how deeply systemic racism affects the lives and birthing outcomes of Black women includes addressing social determinants of health, said Hamblin. Issues that precede a pregnancy, such as homelessness, stress, and obesity, can have substantial impacts on health outcomes when pregnant, and in order to reduce maternal morbidity, people need to enter pregnancy healthier.

“If we say, once a person is pregnant, that's when we want to deploy the resources and say, ‘Now you can have additional food benefits, and now you have vitamins, and now you have a little bit more money on your EBT card’…we've kind of missed a point,” she said.

In 2022, Worcester had an average preterm birth rate of 9.7%, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed by the Virginia-based nonprofit March of Dimes. The city’s highest preterm birth rate of 10.8% was among Black infants, which was more than 1 percentage point higher than the 2022 Mass. average of 9.1%.

The health systems within Worcester aren’t able to keep up with both the city’s rapidly diversifying population and rising rates of homelessness, the latter of which disproportionately impacts people of color, said Love Odetola, visiting assistant professor at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester. The Central Massachusetts Housing Alliance reports that rates of homelessness in Worcester have risen 20% each year for the last two years.

While rates of severe maternal morbidity rose across all races in Massachusetts, Black birthing people were more significantly impacted by the rapidly rising rates than their white counterparts. Black birthing people experienced a 10.1% average increase per year while white birthing people experienced an average 7.8% increase.

Furthermore, rates of maternal mortality among Black people are 2.6 times the rate white people, as reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2021, when using the World Health Organization’s definition of maternal mortality: deaths relating to pregnancy or its management occuring during pregnancy, birth, or within 42 days of the termination of a pregnancy.

Racism in health care

Social determinants of health affect people on a holistic level, and that includes maternal mental health. Though Massachusetts has done a lot of work to improve its mental healthcare system, the barrier to entry is still extremely high, especially for those utilizing public health insurance, said Nancy Byatt, perinatal psychiatrist and executive director of Lifeline for Families at UMass Chan Medical School in Worcester.

“We’ve been in a mental health crisis for decades, and now we're in a mental health emergency,” said Byatt.

In some cases, those on public health insurance need to have three therapy visits before they can be seen by a psychiatrist, meaning those experiencing mental health illness and crisis during pregnancy and postpartum have lengthy waits to get help – time that they don’t necessarily have, she said.

In fact, data from the CDC in 2022 reported 23% of maternal deaths from 2017-2019 were related to mental health conditions with more than 80% of pregnancy-related deaths being preventable.

Though rates of maternal morbidity and mortality are increasing across races for different reasons, for people of color, it’s due to systemic and structural racism, said Diop from DPH.

“The providers within the healthcare system will decide, based on your skin color, who is worthy of quality care, who should get enough information about health, who should be treated with dignity, who should be respected, whose questions should be answered right,” said Diop.

One of the effects of systemic racism embedded through the healthcare industry is Black women are oftentimes not listened to, their concerns brushed off, even when there are lethal repercussions, said Marlina Duncan, vice chancellor for diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer at UMass Chan.

“People maybe don’t feel empowered to speak up because they think, ‘Well, if I do, does it matter? You know, I know the risk. I know that I'm really just trying to come here and survive and give birth,” Duncan said. “That should never be the way that we approach any sort of health care, but especially with giving birth.”

Persistent misconceptions regarding Black pain, including beliefs that Black people have a higher pain tolerance and thicker skin than white people, factor in why Black birthing people oftentimes receive inadequate care, she said,.

“We know that race is a social construct, but it's still playing out as something biological when it comes to patient health care,” said Duncan.

Taking action

A paramount component of attenuating maternal morbidity will be cultivating a diverse workforce of professionals from different racial and ethnic backgrounds, and Odetola said expanding representation among healthcare providers and workers starts long before the hiring process.

“That starts with undergrad,” she said. “That starts with high school, getting kids who were younger from diverse backgrounds interested in medicine, interested in nursing … You got to get started getting them interested in middle school, high school, and then accept them into undergrad schools that are solid.”

When it comes to professionals already in the workforce, Odetola said implicit bias needs to be addressed, suggesting medical schools incorporate addressing structural racism into clinical training, including debriefing with a superior and analyzing how implicit bias may have played a role in interactions and treatments.

“You do that over and over and over again,” she said. “You address perhaps biases that you yourself may not be aware of … It goes beyond just a one time thing, or just a course of two or three courses or training programs. It has to be continuous.”

More comprehensive research on the experiences of Black birthing people, especially qualitative research, needs to be conducted, Duncan said.

“We do need the research to really back what are people experiencing, especially what are Black birthing people experiencing,” said Duncan. “What does that look like for them? And I don't think we have a lot of research on that.”

With hard data on hand, Duncan said, those in positions of power can see where needs are and can subsequently garner the resources to address them.

It takes a village

“What we're seeing when we talk about maternal morbidity goes beyond the four walls of the hospital or goes beyond the clinical setting,” said Odetola.

More doulas could be integrated into the community, Hamblin said. Massachusetts made moves to make doulas more accessible to the public when MassHealth announced in December it would start covering doula care, specifically to help close the gap when it comes to health inequities.

A strong advocate for doula care, Hamblin said patients supported by doulas show lower rates of cesarean sections, increased rates of breastfeeding, and are associated with decreased preterm birth.

Employers can do their part by offering paid maternity leave, allowing women to better take care of themselves and be around the support they need during that postpartum period when complications can occur, she said.

The issue of Black maternal health calls on the community as a whole, said Hamblin.

“As a Black physician and a Black OB/GYN, as a mother, Black women are not broken. There's nothing wrong with Black women. Black women experience the downstream effects of racism,” she said. “It's abhorrent, and no one should stand for it.”

Thank you for highlighting this vital issue. It is unfortunate that our city's recent conference on this issue, and this article, discuss action steps and community collaboration yet neglect to mention integrations of midwifery care as a proven and desired component of the solution for our community. Midwives are extensively trained, skilled healthcare providers with scope of care ranging from pregnancy, birth, and postpartum, as well as reproductive care independent of pregnancy. The midwifery model of care centers families with an empowering and individualized focus.

From the World Health Organization to the March of Dimes to even the recent MA DPH Review of Maternal Health Services, midwifery care and birth centers are being called for as effective means of providing quality reproductive healthcare in a manner that saves lives, improves quality of life and reduces disparities in care provision. The WHO estimates that 87% of reproductive health services could be provided by midwives, and that 83% of maternal deaths, stillbirths and neonatal deaths could be averted with quality midwifery care.

Our community deserves choices in their reproductive care at ALL stages, with access to a competent and diverse workforce of providers. Increasing access to midwives and birth centers are action steps that we cannot afford to ignore. Training more midwives FROM our community FOR our community would create significant and lasting positive impact.

1 Comments