Overall, the amount of available space in suburban Central Massachusetts office markets is more than 90 football fields.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Urban cores across the country have been hollowed out in the last five years, as the rise of remote work in the wake of COVID added to problems caused by offshoring and automation. This has brought about the rise of so-called zombie buildings: underutilized offices with high turnover and a narrowing path to financial viability.

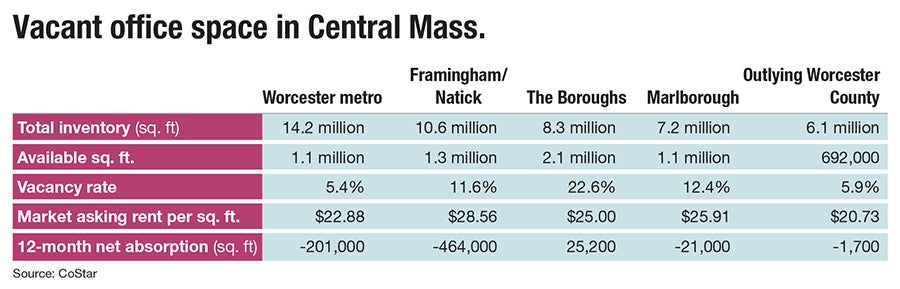

This outbreak hasn’t seriously infected Worcester’s urban core, where office vacancy rates aren’t nearly as troubling as Boston and other large cities like St. Louis or New York City. The vacancy rate in Worcester sits at 5.4%, according to CoStar, significantly less than the rate of 17.7% in Boston’s Financial District or the 10.4% in Providence.

Instead, the region’s office vacancy problems lie in more suburban areas, where rates sit around or above the national average of 13.9%. Northborough, Southborough, and Westborough have been particularly hit hard, with a total vacancy rate of 22.6%.

Overall, the amount of available space in prominent suburban Central Massachusetts office markets is 5.19 million square feet, more than 90 football fields.

Long gone are days where properties lacking highway access and amenities could coast on the strength of the overall suburban office market, with some buildings sitting underutilized, or even empty, for years.

Shrinking demand for and value in office space has property owners and their financial backers trying to find a path forward, hoping their buildings can find new use and municipalities are willing to accept the changing tides.

“When that ratio of supply and demand gets out of sync and there becomes way too much product on the market with, then what happens is pricing just starts to go through the floor,” Jim Umphrey, principal owner of Worcester real estate firm Kelleher & Sadowsky, said of suburban space. “One thing is true is that a lot of these buildings will never be used as office space again.”

Urban core

The Worcester office market’s relative strength has been a bright spot in the Central Massachusetts office market, said Umphrey.

“I would say downtown Worcester is faring much, much better than the suburban areas,” he said. “A lot of these suburban buildings, these big, sprawling buildings that had tech companies or other uses in there, are going to get repurposed as something else.”

Worcester has about 1 million square feet of Class A office space, said Umphrey, which comprises buildings with high-quality finishes, the latest technology and amenities like on-site concierge services. Downtown space offers lunch and afterwork entertainment within walking distance, which the younger generations of workers see as a plus.

“If you're in 100 Front St., you've got 10 restaurants that are within walking distance.” Umphrey said, referencing the 20-story Mercantile Center tower with next-to-zero vacancy. “ That has been really driven by the younger generations. They're the ones that are saying, ‘If we're going to come back to work, this is what we want.’”

Worcester’s vacancy rate is improved by some office properties coming off the market by being slated to be converted directly into housing or other uses, with the most prominent example being One Chestnut Place, the former headquarters of insurer Fallon Health, which Boston-based real estate firm Synergy has plans to convert into a 198-unit residential tower.

Suburban struggles

The suburbs are a different story. At least seven office buildings in the Boroughs adjacent to Route 9 are more than 20,000-square-feet and under 50% leased. One of the more prominent examples is 900 West Park Drive in Westborough, a 193,228-square-foot, four-story building built in 2000 but was never occupied, which has sat unused for a quarter-century.

Constructed on speculation, it appeared EMC Corp. would occupy it prior to its merger with Texas-based Dell, but the company never ended up needing the space, said Umphrey. It was later sold to the growing Westborough software firm eClinicalWorks, but with the trend of remote work emerging during the pandemic, the company elected to not utilize the site it still owns.

Other Westborough business park space has been adapted for other uses, including a former Data General building being converted into an Amazon last-mile fulfillment center.

With the value of suburban office buildings tanking, banks are increasingly extending the maturity of impaired commercial real estate mortgages, choosing to pretend things aren’t that bad to avoid writing off their capital, said Jim Bartholomew, vice president at R.W. Holmes Commercial Real Estate in Wayland.

“Owners are going to do whatever they can that could potentially make sense to make [properties] work,” Bartholomew said. “We’re clearly in a place where office values have plummeted and banks have been doing the extend-and-pretend thing. They don't really want these properties back, and they're open to anything.”

The decline in demand for suburban office space has had a surprising impact for some office space. Amenities, which were once a turn-off for potential tenants, now suddenly give buildings a better chance at a new life.

“Ten years ago, if you had a freight elevator in your building, it was a big red flag,” Bartholomew said. “It was a black mark against the building. Now it’s a huge advantage. Office and office-flex buildings which have freight elevators and loading are able to adapt much better.”

These features make bringing in equipment for R&D or light manufacturing uses much easier, avoiding having to demolish walls or take out windows.

The building’s aesthetics and size play a role too, said Elizabeth Holmes, director of corporate services at R.W. Holmes.

“The buildings that have a nice image have been well kept and can subdivide below 5,000 square feet, or even below 3,000 square feet, still have really good occupancy,” she said. “It's the stuff that has big swaths of workspace that starts to struggle. Subdividing can be prohibitive because of the cost for a lot of the owners, depending on what they've bought the building for.”

Owners are having to consider new uses in addition to potential subdivisions, including uses like medical space, which some landlords used to avoid, feeling it clashed with office tenants.

“It's not everyone's cup of tea to have medical uses in their building, depending on what you've got for existing tenants,” she said, “but we're certainly still seeing that health care, medical field, still needing the office space when maybe a tech company doesn't.”

Municipal pushback

One of the challenges of converting office buildings into other uses can be achieving buy-in from the city or town. That’s even more challenging when your property is split in two by a municipal border.

That’s the situation for the 93,088-square-foot former office building located off of Pleasant St. in Framingham. The building is split in two by the municipal border with Southborough, which added challenges to a project U-Haul started in 2019 to gut the shell of the building and convert it into a 636-unit self-storage site.

“Our biggest challenge there was zoning,” said Scott Chase, president of Methuen-based U-Haul Co. of Eastern Massachusetts. “Framingham was very much not in favor of our project there. But by the end, I think we won them over. But from their perspective, it was ‘We want to fill these back up with office workers.’ That's great, but times change.”

After finally receiving approval from both municipalities to move forward, next came the challenge of converting the space. The unique-looking building’s lower concrete structure was constructed in the 1960s, with the couple of glass floors above it added in the 1980s.

“There were a lot of engineering studies,” Chase said. “We had to go in to figure out how to carry the floor load. Typically, storage rooms are not structural, and they're not load bearing, so we had to do some work there to make sure that the building was going to work for what we wanted to do. But in the end, it worked out great.”

Like more urban offices, some suburban buildings are being converted directly into residential space in the rare instances where the building’s design and infrastructure allow for it. One example is a long-vacant office at 130 Lizzotte Drive in Marlborough, which Southborough-based Ferris Development Group is working to convert into residential space as part of a larger planned 180-unit complex.

Ferris has been converting other MetroWest spaces, including a former 57,000-square-foot office building at 250 Turnpike Road in Southborough, into locations for BeeHive, a handyman repair services company, which provides space for contractors of various skill types and helps connect them with customers.

Other projects will require buildings to be torn down and reconstructed as structures more suitable for residential uses. Either way, cooperation from municipalities is needed, said Holmes. She said a proposal being floated by Westborough-based Carruth Capital to convert a 364,800-square-foot office campus at 500 Old Connecticut Path into a potential mixed-use site featuring residences has received some pushback.

“Framingham is pushing back on that because of the dual tax rate, and that becomes a lower tax basis as a residential project, rather than it being a commercial project,” she said.

Framingham and other municipalities are attempting to come to terms with the fact that office tenants aren’t coming back, said Holmes, as they may be facing more property owners requesting tax abatements for underutilized office space.

“At some point, there has to be a reckoning and a partnership moment between the municipalities and property owners,” she said.

Eric Casey is the managing editor at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the manufacturing and real estate industries.