For Worcester business owners, operating a second-hand shop in the era of fast fashion means strategic buying, knowing the consumer base, and educating the customers is all in a day’s work.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Will Daughtry got into the second-hand clothing industry explicitly for the culture, but it didn’t stay that way.

“In the beginning, it was fashion and glory. You're getting things at a premium low price; that was the beginning stages,” said Daughtry, the owner of Worcester vintage and second-hand store Concrete Collection. “But when you start to venture into the business world and you meet people, they want to know what you're truly in business for. And always in this space to not know anything about sustainability and the effects on the wasteful textile garment industry … kind of a bad business practice not to know and be educated about it.”

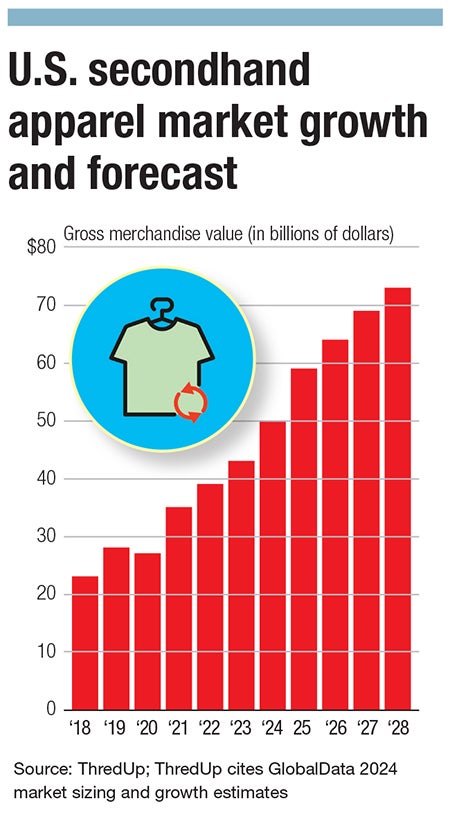

Thrifting is skyrocketing in popularity, with estimates forecasting the industry’s gross merchandise value will surpass the $70 billion mark in the U.S. by 2028, according to data from online thrift store ThredUp. At the same time, the rise in fast fashion and brands such as Shein, the Singapore retailer valued at more than $50 billion, have made clothing more affordable and accessible for the everyday consumer while contributing to environmental pollution and exploitation of workers.

For Worcester business owners, operating a second-hand shop in the era of fast fashion means strategic buying, knowing the consumer base, and educating the customers is all in a day’s work.

A tug and pull

Reselling fast fashion is an absolute no for Maria Pappas, owner of the consignment shop Modern Muse in Worcester. Her love of fashion runs in her family: Pappas’ father was a tailor who used to make clothes for her and her mother.

“I started sewing early, early on, and I just loved having certain one-of-a-kind pieces,” Pappas said.

And it is these one-of-a-kind pieces Pappas looks to fill her storefront with, specifically pieces that will last. Fast fashion pieces wear quickly, and she wants her customers to be able to enjoy their garments for years.

“I just wanted to find used clothing that was interesting and reinvigorate and have them become alive again,” she said.

In contrast, Molly McGrath, owner of Grime, a vintage and second-hand clothing shop in Worcester, is happy to resell fast fashion pieces if she thinks her customers will be interested. Though she’s conscientious not to stock up on too many fast fashion items, as those are not the kinds of garments her patrons are coming to her for, she isn’t averse to the idea.

“Stuff will come in here that's, you know, Shein or even Forever 21, and I'm like, if it's still cute and I think it's still workable and I know a customer that I think would buy it, then I'm gonna move it,” said McGrath. “Instead of just keeping it vintage and keeping it, you know, just one type of clothing, I'll take a little bit of everything in here. I'm more about knowing my customers and knowing what's moving right now and what I can flip is more my mind frame.”

McGrath said there’s room for both fast fashion and thrifting in the clothing sector, noting solely buying vintage is a costly endeavor. People buying fast fashion are not in the dark about the effects of the industry on the planet and people, she said, but it’s more complicated.

“It's hard because you always want to do the right thing, but it's also like, we're all scraping by, you know? We're all surviving on our budgets and our lifestyles,” she said.

Though neither Pappas nor McGrath see the rise in fast fashion affecting their businesses at the moment, Pappas foresees major players in the fashion industry incorporating second-hand clothing into their business strategies.

In fact, the likes of Nordstrom and Neiman Marcus have already made efforts at utilizing the thrifting trend by partnering with resellers to provide second-hand options for their mainstream customers.

“They're going to find really good stuff, and then they're going to jack the prices up and say, ‘This a vintage piece’,” Pappas said. “They're going to be taking a portion of the business away from the consignment stores.”

A sustainable practice

Comfortability is a crucial catalyst for shoppers purchasing fast fashion, said Daughtry.

“A lot of people still don't quite understand this (second-hand) market yet. So you're going to shop where you're comfortable,” he said. “You're going there to shop and understand what is presented to you, and fast fashion does that better than anybody else.”

Daughtry can’t always take everything people bring him to sell. But to make sure those clothes don’t end up in the trash, he incentivizes customers to donate the clothes locally by matching the store credit or discount those organizations gives them in return at Concrete Collection.

McGrath encourages sellers to recycle their own wardrobes, by offering sellers 30% of her resale price in cash or 45% in store credit – making her own pieces more accessible to customers.

A large part of accessibility is affordability, and affordability is a pillar of Daughtry’s business model.

“When it came to affordability, it's understanding margins. It's like, people don't want to walk into the store and leave empty handed because they couldn't afford it,” said Daughtry. “The bigger we get, I want to go lower with our price margins because I tell people all the time, ‘I can sell a thousand $5 t-shirts and make money; I don't have to sell 100 $100 t-shirts.”

Daughtry could sell affordable clothing, buying deadstock from the Walmarts and Targets of the fashion space and marking the prices down, but he’s not just in this for the money.

“I'm not gonna give up everything that I know morally and business-wise to compete financially as a business. That's not right,” he said.

Old industry, newcomers

Not everyone who comes into Modern Muse is looking to shop sustainably, but Pappas has noticed both older customers and college students have been educated on the effects of fast fashion, naming specifically those from Worcester Polytechnic Institute as the most intentionally eco-conscious shoppers.

McGrath has noticed an uptick in young buyers as well, some so young their parents are still footing the bill.

“Right now, it's super cool to thrift, and it's super cool to find something at Savers, or find something here, and post it on Instagram,” McGrath continued.

For Daughtry, who himself started thrifting as a teen with money he earned as a dishwasher, educating his customer base on the importance of sustainability is paramount.

It was easier to make people care and understand during the coronavirus pandemic when, as he put it, the monster that is the consistent shopper was slowed.

As shops opened back up and people weren’t scared anymore, convincing people about the importance of sustainability grew harder.

Daughtry has taken on the role of not only owner, but educator, giving customers the lowdown on where the garments they’re buying come from, how he’s tie-dyed or bleached them to revive them, and the good the customer is doing in not contributing to wasteful impacts.

Even with all his efforts to support sustainability and educate himself and others, the decision to support the work he and others are doing in the second-hand industry is up to the customers, Daughtry said.

“I'm going to wash this, curate this, steam this, and press this for you. We're going to put it in one location. You have to decide whether you're going to be a part of the problem or you're going to be a solution,” he said.