Known as the sandwich generation, many middle-aged people in the U.S. today are performing a balancing act, working while supporting older children in high school and college, and caring for an aging parent or other loved one who is no longer independent.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Known as the sandwich generation, many middle-aged people in the U.S. today are performing a balancing act, working while supporting older children in high school and college, and caring for an aging parent or other loved one who is no longer independent.

According to a 2022 study from the University of Michigan, such a lifestyle is common, with nearly one quarter of adults who care for a parent over the age of 65 still responsible for at least one minor child at home.

These responsibilities take a toll. Sandwich generation caregivers are nearly twice as likely to report financial difficulties, as well as emotional difficulty, compared to their peers who care for an aging parent but without children still at home. Just as they may have done when their children were small, these people need to carve out time for their wellbeing, whether to relax, exercise, or socialize.

Taking a break or engaging in an activity designed to bring personal joy or fulfillment often comes with a sense of guilt. Caregivers may even find it hard to prioritize basic needs such as exercise, medical care, or eating.

But without a breather, a caregiver can run the risk of harming their own physical and mental health, leading to depression or anxiety, which can affect their ability to adequately help those for whom they are caring.

Heather Dobbert, a social worker and clinical integration behavioral health case manager for Worcester health insurance company Fallon Health, said she encourages caregivers to cast a wide net for support, and to welcome offers of help. Churches, senior centers, seminars and even blog communities can make the challenge of caregiving less lonely.

“People should explore all avenues to make sure they’re not doing it by themselves,” Dobbert said. “If someone offers help, what does that look like? Can they mow the lawn, can they pick up groceries?”

A caregiver’s burden doesn’t just affect one area of life; the sustained stress can affect other responsibilities as well as relationships. Caregiving can be a drag on time, personal development, physical health, social engagement, and emotional well-being.

Finally, don’t underestimate the importance of a respite to the person for whom you are caring. There is a good chance they need a break as much as you do.

Creating care anywhere

Here are some ways for caregivers to physically and mentally cope with the stress of their responsibilities:

Plot a getaway

Taking time away from caregiving is actually important to providing quality care for others.

According to the AARP's Prepare to Care Guide, “Stress can negatively affect your health, well-being and ability to provide care. Schedule regular time for what is important to you and get help from others.”

Even an hour away for lunch or time with friends and family can be helpful.

Think physical first

It is vitally important to make sure you are attending to your own physical needs. An estimated 70% of caregivers experience a decline in their own health. The downturn is often exacerbated by poor diet, lack of exercise, and poor sleep.

Seek help

Caregivers have a tendency to wait too long to ask for help. Many caregivers do not recognize the stress they are under, so it is a good idea to listen to others when they offer help or express concern.

Nearly half of caregivers do not seek any help, according to the Family Caregiver Alliance.

Not only can a support group connect a caregiver with like-minded people experiencing similar challenges, the meetings also offer a break from the day-to-day tasks that become commonplace.

Regular meetings with a therapist or counselor can also be beneficial. Many elder services organizations – regional access points for federally funded programs that assist the elderly – run caregiver support groups.

Deb Dowd-Foley, a longtime caregiver support specialist for Elder Services of Worcester Area, encourages caregivers to take advantage of any resource available in the community to avoid isolation.

“Caregiver support groups are free. It’s a chance to be with others who are going through what you are going through,” Dowd-Foley said.

Know your rights

It is OK to get upset as a caregiver. You might even feel depressed from time to time.

These feelings aren’t unusual. In fact, negative emotions are an expected part of caregiving, as spelled out in author Jo Horne’s Caregiver Bill of Rights in her 1985 book, “Caregiving: Helping an Aging Loved One.”

“I have the right to … get angry, be depressed, and express other difficult feelings occasionally,” it reads.

To avoid getting stuck in negative emotions, empowerment is key. Dowd-Foley recommends reaching out to the local office of the statewide Family Caregiver Support Program such as the Elder Services of Worcester Area chapter, in order to find out what resources you and your aging loved one qualify for. In some cases, an adult day program that provides engaging activities and socialization may provide relief during work hours.

Dowd-Foley encourages people to talk to workplace human resources departments about flexible work arrangements to allow for daytime caregiving and to explore Family Medical Leave Act options as needed.

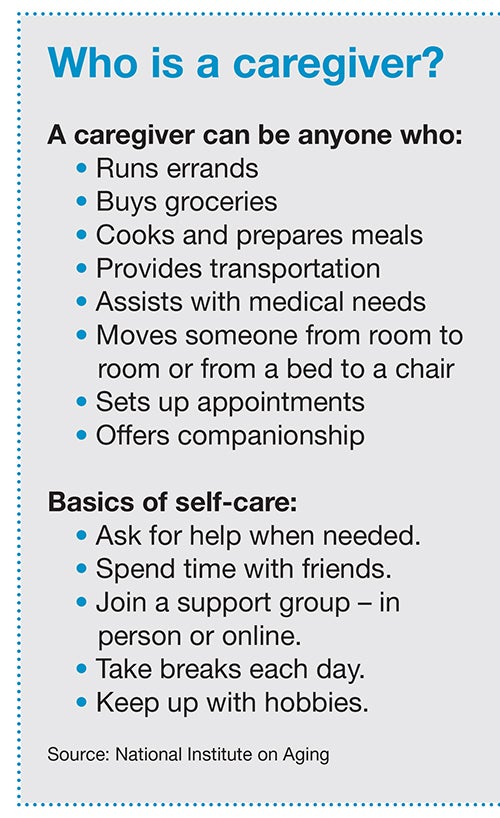

Sources: AARP; National Institute on Aging; Family Caregiver Alliance; Alzheimer’s Association; American Heart Association; University of Michigan