Smaller cannabis companies are white labeling and collaborating as they try to survive a fierce pricing competition against large corporations in an increasingly saturated market.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

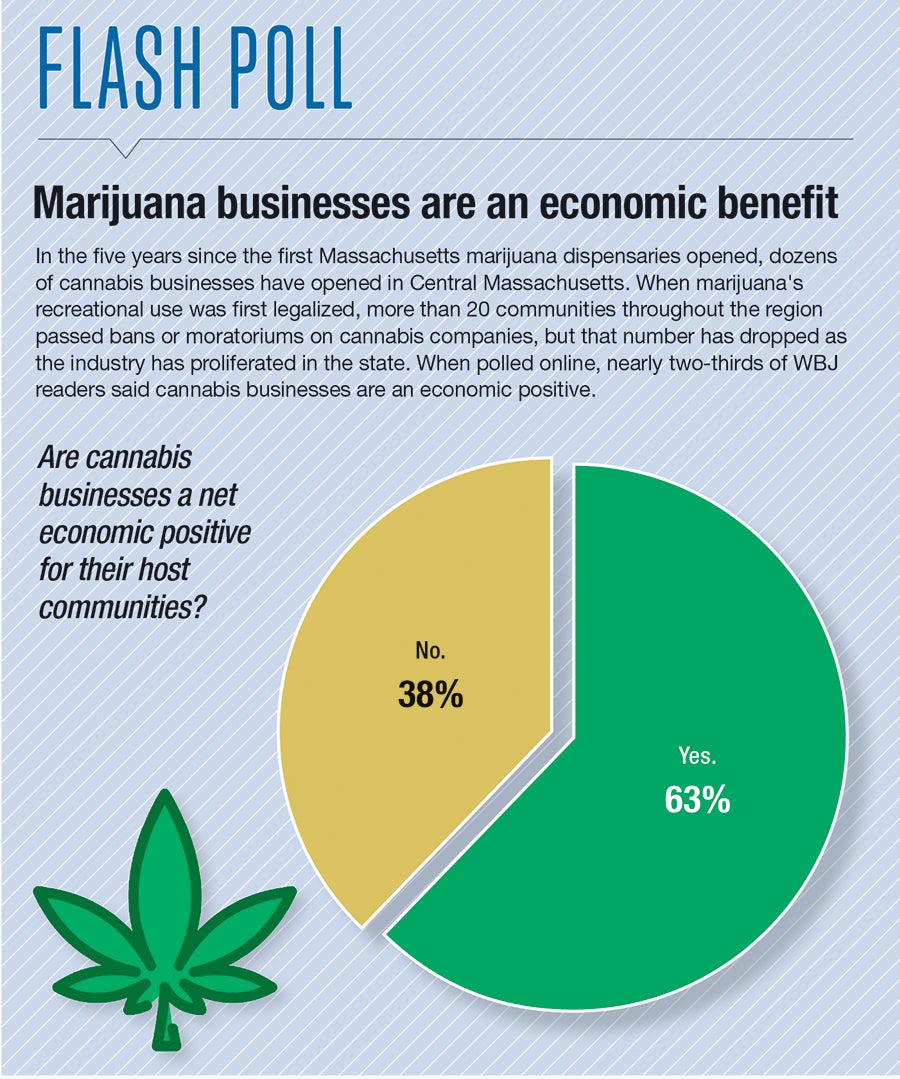

The times when customers used to be shuttled from offsite parking lots to dispensary doors feels like a cannabis market creation myth. With 286 adult-use dispensaries open in Massachusetts, finding cannabis for purchase is as increasingly simple and straightforward as buying a six-pack of Sam Adams.

That market saturation is bringing with it a host of challenges, especially for smaller and locally-owned cannabis companies competing with larger, multistate operators. The battle for survival – and dominance – is playing out on shop shelves and at cash registers.

“The retailers really have all the control,” said Kevin MacConnell, co-owner of Yamna, a cannabis microbusiness based in Uxbridge.

This November, adult-use cannabis sales will have been online for five years in Massachusetts. In the early days, consumers traveled to one of only a handful of open adult-use dispensaries — the first two opened on the same day in Leicester and Northampton — and were subjected to a myriad of obstacles, including shuttle buses, lengthy outdoor lines, and little to no ability to casually browse products. Going to the dispensary was an event in and of itself; a novelty.

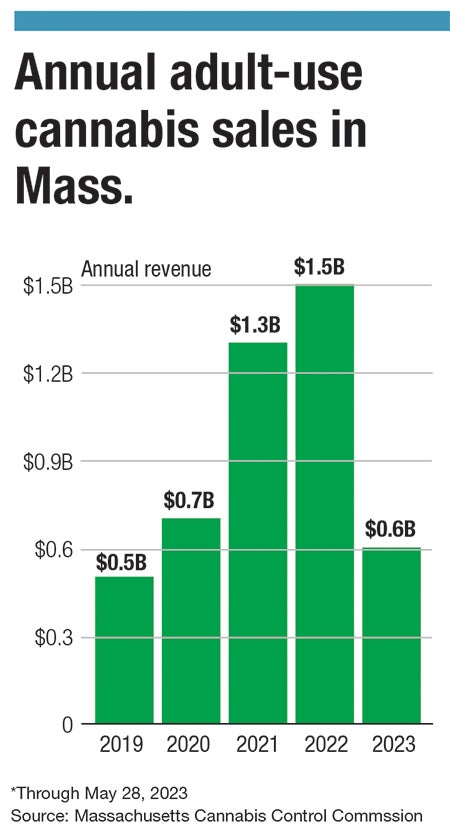

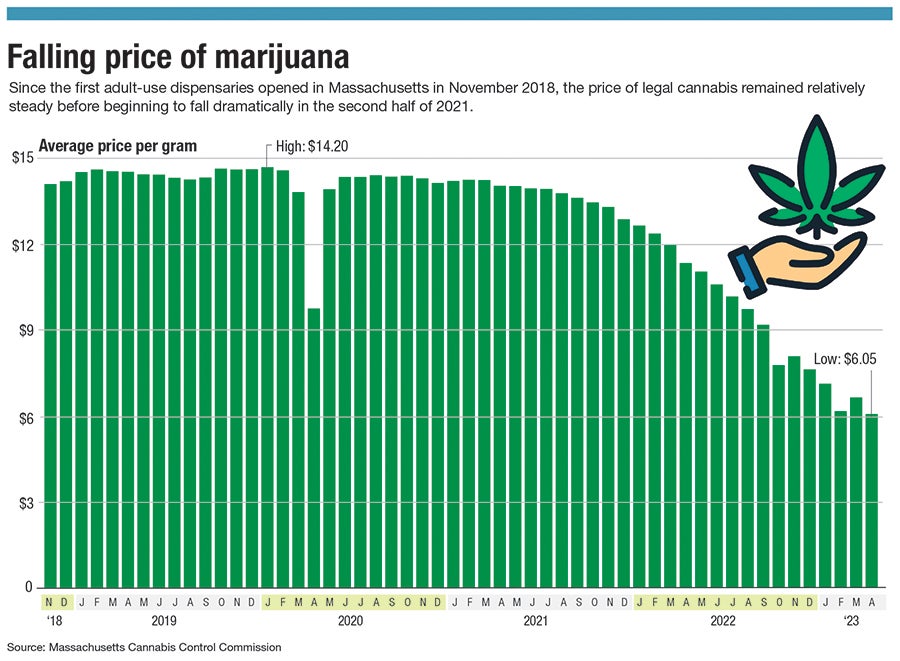

Back then, the retail price for a gram of cannabis flower hovered just above $14 a gram, according to historical data from the state regulatory agency Cannabis Control Commission. While there was a lot of crosstalk about whether customers would pay the premium for regulated, legal cannabis when the legacy black market was known to offer much lower prices, consumers ultimately turned out, with dispensaries reporting $500 million in adult-use sales in the first full year that adult-use sales were open, according to the CCC. The regulatory body’s tracker now reports annual adult-use sales in the billions.

As of May 21, the CCC reports $4.56 billion in gross adult-use sales since November 2018, with more than half a billion of those dollars coming in in the first five months of 2023, alone. Meanwhile, the average price of a gram of flower is $6.05, a 57% decrease from when dispensaries first opened.

But as the adult-use market embeds itself into daily life in the commonwealth, the pressure is on for cannabis companies to provide customers with the products they want at the best possible price, resulting in what local owners are calling a race to the bottom.

White labeling

“Given our small size and how quickly wholesale flower has tanked price-wise, it’s very hard for us to even come close to some of the wholesale pricing larger companies can offer because we just can’t produce at this volume,” said MacConnell, of Yamna.

Yamna grows and sells its own flower and other cannabis goods to retailers, including its flagship product: the cannagar, a specialty two-gram pre-roll handwrapped in hemp with a reusable glass filter. Yamna, one of the first two cannabis microbusinesses to open in the state, cannot retail its products directly because the company is not yet eligible for a delivery license, a classification temporarily limited to economic empowerment and/or social equity program participants, which Yamna is not. This means the company cannot vertically integrate.

Because of this position, co-owners MacConnell and Tim Phillips have an up-and-close view of a supply-and-demand ecosystem pressurizing the adult-use market. While dispensaries stock a variety of cannabis products, at the end of the day, consumers are in large part looking for the highest THC concentration for the lowest price, and retailers are following suit.

“Some stores, all they’ll want is 30% or higher [potency],” MacConnell said.

To stay in the game and continue attracting customers, Yamna and other companies have had to get creative and make some concessions. When Yamna first wholesaled its cannagar, the company sold it to retailers for $25 a piece, with the hope retailers would sell it to customers for about $50. Yamna has since dropped its wholesale price to $15, with the hope its cannagars will retail from $25 to $30, although the company has little control over the final retail price.

From 2021 to 2022, Yamna’s revenue dropped 7.5%, while its wholesale output increased 40%.

To combat the pricing battle, Yamna is taking the same track as some of its other small business peers: collaborating with other cannabis companies. In Yamna’s case, the company is forming partnerships with other cultivators and manufacturers who send their flower and/or oil to Yamna, which charges a processing fee before then turning that raw material into a cannagar. These co-branded products are in Yamna packaging, but include a hanging tag indicating whose raw material is in the cannagar, as well as information about the strain. As a microbusiness, Yamna is limited on how much flower it can cultivate; these kinds of relationships allow the four-employee company to increase its wholesale output while working together with other growers.

Bud’s Goods & Provisions, based in Worcester, is taking a similar approach, said Alex Mazin, the company’s president and CEO. Although the company is integrating cultivation and manufacturing into its business, Mazin said its wholesaling is not at the same scale as the larger, sometimes multi-state operating competition.

To keep up with the pricing war, Bud’s Goods has begun purchasing flower in bulk and packaging it under the Bud’s Goods retail label, a way both allowing the company to access more flower and keep prices down for customers. Mazin is chipper about this move, saying this allows the company to conduct internal quality control, ensuring product weights are more accurate and stamping the product with the company’s seal of approval. This helps Bud’s Goods compete against larger cultivators, which are able to drastically drop prices to move large quantities of product, especially flower not selling as quickly as anticipated, two hits a smaller business can’t often afford to take. Beginning last fall, Bud’s Goods began selling these white-labeled flower products in monthly bundles.

The bundles are advertised in banners on the company’s website, where customers encounter another way Bud’s Goods aims to stand out: curating a monthly menu Mazin likens to a cocktail list at a bar or a weekly grocery store flyer. Bud’s dispensaries still stock the vast array of products available at most cannabis shops, but they advertise a select number of items front and center, to help avoid what Mazin calls the paralysis of too many options.

No longer a field of dreams

As stigmas around cannabis use shift and consumption becomes more socially acceptable, cannabis companies are changing their approach – or they should be – said Brittany Wong and Brent Martino, CEO and creative director, respectively, of Worcester marketing agency Studio Jade, for which the majority of clients are cannabis companies.

“In the beginning, it was the kind of ‘Field of Dreams,’ if-you-build-it-they-will-come model,” Martino said. “It’s not like that anymore.”

Retailers ought to understand buying cannabis is now a shopping experience much like any other, and that means taking to heart how normal cannabis consumption is becoming in Massachusetts. Wellness, Wong said, is on its way out; people use cannabis for fun, and they’re more comfortable saying that.

That shift, she said, is impacting buying trends. Items traditionally associated with the wellness approach for cannabis use — tinctures, capsules — are less popular. Recreational categories of products are more in demand. To stand out, Martino and Wong pointed to the great white whale of advertising: authenticity. Martino used a mall analogy: Dozens of stores all sell clothing, but each store looks and feels different, while coexisting. Cannabis, he said, should work the same way.

Yet, that analogy only goes so far when so many players are competing for space in the proverbial shopping center.

“We are definitely headed for a market correction,” Martino said. “You just can't in a state like Massachusetts have this many dispensaries.”

Everyone interviewed in this piece advocated for policy changes to make it easier for locally-owned and smaller cannabis companies to stay competitive. Mazin and the Yamna co-founders lamented the heavy tax burdens their businesses face, particularly at the federal level, where MacConnell said Yamna is taxed on its gross profit, not net revenue. While this was reformed at the state level last August, it has not changed federally, where cannabis remains illegal.

Wong and Martino, in turn, pointed to the strict rules cannabis companies face around marketing, which limits loyalty programs, as well as advertising in general. When companies are fighting for customer loyalty in a market with an overwhelming amount of options, this poses a particular challenge, especially when financial penalties for breaking regulations can disproportionately burden smaller companies.

This backdrop has forced innovation and collaboration, but at the same time, the market appears to be waiting for the other shoe to drop: not everyone can possibly survive the squeeze.

“It’s the only way to survive now,” said Phillips. “We’ve got to be different.”