This new way of life has rearranged the real estate and construction industries, just like practically every other part of the economy.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

For a long time, a main part of a real estate home search included an open house packed full of potential buyers; while at busy office buildings, coworkers stayed in close quarters with colleagues.

For now, at least, none of that is possible, thanks to the coronavirus pandemic.

This new way of life has rearranged the real estate and construction industries, just like practically every other part of the economy.

Office tenants, with many workers staying home, have been putting more subleasing space on the market. Some construction has stopped, although certain sites have continued operating with new health measures in place. Realtors are holding showings virtually, and potential buyers are foregoing the ritual of standing in a living room or kitchen and picturing it as their own.

“We used to have open houses with 50 people,” Bill Dermody, the chairman of the Greater Boston Real Estate Board, said in an industry webinar hosted by Peabody real estate data firm The Warren Group. “That changed immediately. You’re not going to see that again in the near future. You’re not going to see that again in the far future.”

Residential, commercial and industrial buyers are figuring out how long people will be forced into social distancing and how deep a recession will get. Little data yet shows how much the market has changed, as the pandemic is so relatively new, a clear picture on the impact to sales and rentals has yet to emerge.

Commercial and industrial real estate

Commercial and industrial sales already in the works typically followed through once the pandemic hit, and new lease deals driven by expiring leases largely continued. Besides those, deals are being paused to see how the virus continues spreading and what it means for the economy.

“Most other deals have been put on hold,” said Aaron Jodka, the managing director for research and client services for the Boston offices of Colliers International, a real estate services company. “If you have to transact, you are. If you don’t, you aren’t.”

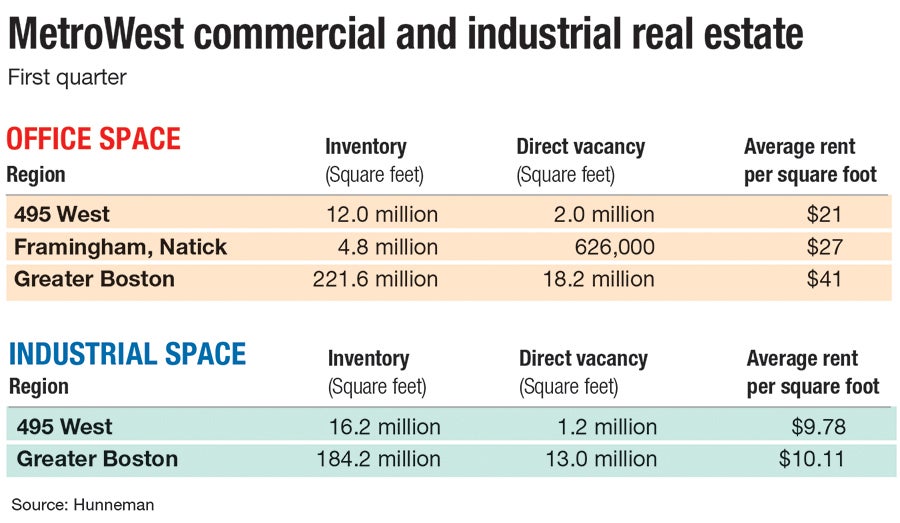

Offices are largely empty today with stay-at-home orders, but employers are typically locked into longer leases than what would allow them the flexibility to make shorter-term decisions such as shrinking space permanently or moving to a suburban location, said Tucker White, a research director for the real estate firm Hunneman in Boston.

Los Angeles realty firm CBRE, which has a location in Boston, said the office market should take far less of a hit than it did in the 2001 and 2008 recessions, though construction delays will lead to a slowdown in supply. Industrial properties should be boosted by retailers and manufacturers looking to carry more inventory than they would have previously to be better prepared for any similar disruption in the future.

White said a shift to more online buying combined with a longer-term trend of industrial space being pushed out from inside the Route 128 belt will help the industrial market in farther-out areas like along I-495.

As for hotels, CBRE expects a 30% decline in demand this year and a 10% drop in daily room rates. Demand won’t recover until around the end of 2021, and room rates by 2022, the firm said. Malls will have vacancy rates increase by 5% to 6%.

A major disruption in the hotel industry could leave a mark on Worcester, where 262 rooms are planned for hotels across from the $132-million Polar Park baseball stadium – where construction has been halted during the pandemic – and a 105-room hotel is proposed for Washington Square.

Reduced retail spending, and a shift to online, could complicate plans for a mixed-use redevelopment of Worcester’s Greendale Mall, finding tenants for dozens of empty storefronts in and around downtown, and retail space planned next to Polar Park.

Residential real estate

The pandemic has caused a drop in new listings after inventory has already tightened dramatically.

“We really have a significant shortage of homes for sale here in Massachusetts,” said Kurt Thompson, the president of the Massachusetts Association of Realtors and a Realtor at Keller Williams Realty in Leominster.

In March, roughly 8,374 homes were listed for sale across the state, Thompson said. That’s down from 12,486 in the previous March and a fraction of the more than 38,000 homes listed at the height of the market in 2006.

In the city of Worcester, 80 single-family homes were on the market in April, down from 104 a year ago, said Erika Hall, the president of the Realtors Association of Central Massachusetts. In February, listings were half of last year’s number, at 57.

“That was a crisis level,” Hall said.

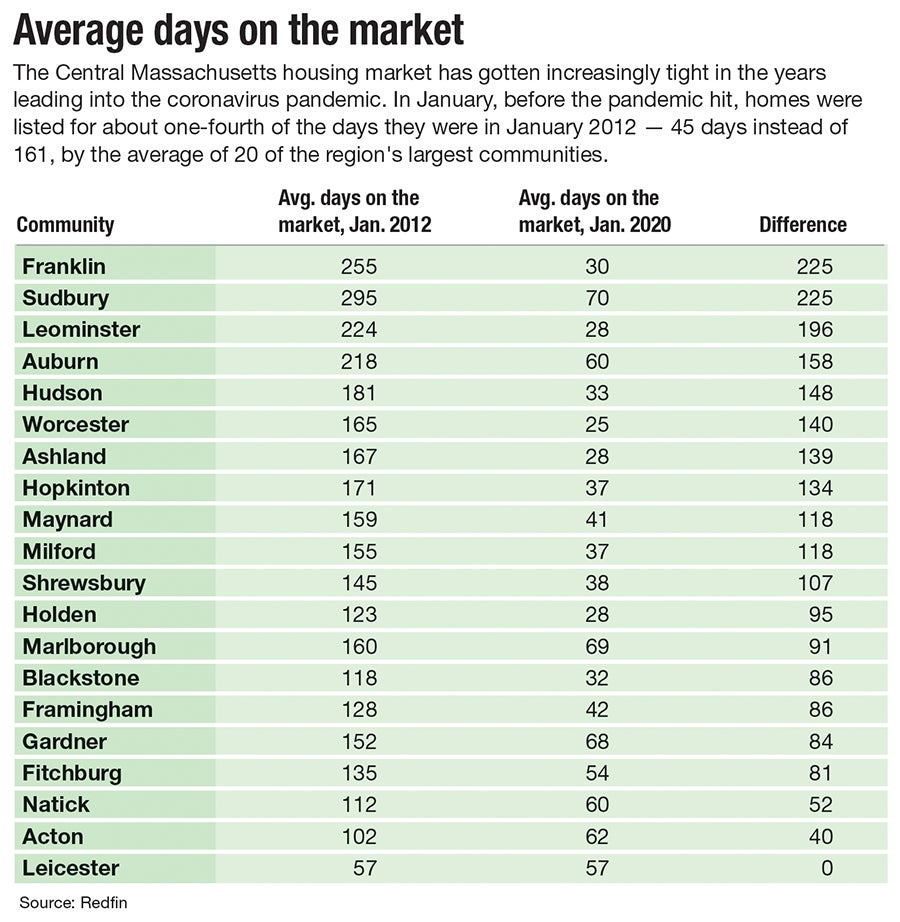

Homes across Central Massachusetts are on the market for a fraction of the time they used to. Across 20 of the area’s largest communities, 19 had averages of homes lasting more than 100 days in 2012, but by the start of this year, none of those communities had an average higher than 70 days.

Another factor could combine with a low inventory to keep prices afloat: rock-bottom interest rates.

“They’re historically low rates. How can you beat it?” Dermody said. “You can afford so much more.”

National mortgage loan company Fannie Mae is forecasting home refinancing, which takes advantage of low rates, to jump $400 billion to $1.41 trillion compared to last year. But it is predicting a big decline in sales: 15% for 2020 compared to last year, it said in April.

Realtors are adjusting to the pandemic by changing how they show homes. Hall has set up cameras in homes for 3D online showings, turning to brief walk-throughs only when necessary.

Before, someone might sit at a kitchen table or on a sofa and picture how they’d feel living there, Hall said. That’s not possible today. When walk-throughs are being conducted, some homeowners are leaving doors open and lights on so there’s less anyone would need to touch.

“You really just need to walk through quickly,” she said.

Residential real estate leaders are optimistic the late summer months will make up for a slow spring and early summer. The disruption now is health related, Dermody said, unlike the home market bubble bursting before the 2008 recession.

“We stand a pretty good chance of coming out of this reasonably well,” said Timothy Warren, the CEO of The Warren Group.

Construction

Beyond buying, selling and leasing real estate, COVID-19 has altered the timeline for completion of construction projects.

Polar Park construction has stopped – putting an April 2021 opening at risk – and College of the Holy Cross in Worcester has stopped work on two major projects, a $107-million performing arts center and the $30-million recreation center.

Others have continued, including the Courthouse Lofts development with more than 100 units in Worcester’s Lincoln Square, an $80-million building at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and a $45-million office building going up in Westborough for the medical optics firm Olympus.

“People are scrambling, for sure,” said attorney David Fine, a partner at the Westborough offices of the firm Mirick O’Connell, who specializes in construction law and litigation.

Sites where work has proceeded have had to take extra precautions, Fine said, including special washing stations and dedicating someone to oversee distancing and other compliance. That’s led to questions about who – the owner or the developer – will pick up extra costs. The same question is being asked of whether a builder could be liable for penalties for finishing a project late if it’s because of a pandemic.

A clause called force majeure, the legal term for an act out of one’s control, has been often invoked for extending construction timelines, Fine said. He’s been advising clients on those terms as well as whether construction workers should be forced to show up on the job during a difficult time.

“You’re seeing a real variety in terms of contractors in how they approach this,” he said.