More than two years have passed since entrepreneur Ross Bradshaw embarked on the licensing process to open New Dia, a recreational cannabis dispensary in Worcester.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

More than two years have passed since entrepreneur Ross Bradshaw embarked on the licensing process to open New Dia, a recreational cannabis dispensary in Worcester.

Now, with a provisional license in hand, he hopes to receive final licensure – the final OK before opening – for his 118 Cambridge St. shop by August. When New Dia opens its doors to the public, the store is set to be the first minority-owned dispensary to open in Central Mass., and only the second or third in the state.

While it sounds monumental – and it is – the development is long overdue in an industry, on paper, is supposed to consider and prioritize the economic interests of minorities and communities disproportionately impacted by the War on Drugs, as was stated in the 2016 ballot measure creating the industry.

“I don’t take pride in saying we’re the first minority-owned [cannabis] business [in Worcester],” said Bradshaw, a black entrepreneur who grew up in the Washington Heights neighborhood.

Despite the call for diversity in the industry’s founding documents, the number of applicants of color to the Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission has been small, due to the lengthy approval process with multiple local and state regulatory hurdles and the large startup costs needed at a time when banks aren’t financing marijuana businesses. CCC has put programs in place to help promote diversity, but they have yet to yield a drastic change.

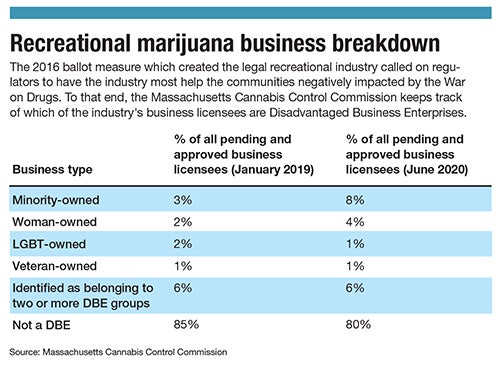

In a state that is 20% people of color, according to the U.S. Census, 8% of recreational marijuana businesses licensees – either approved or pending – are minority-owned.

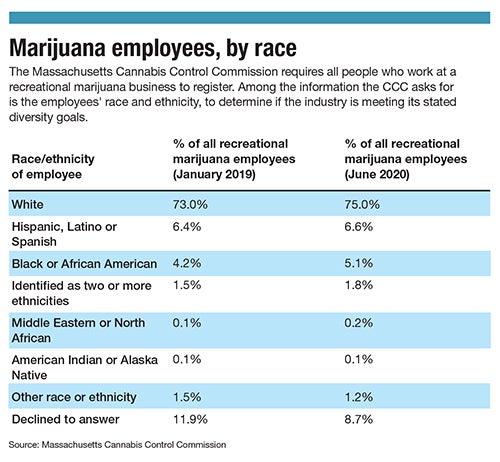

Among all employees at Massachusetts recreational cannabis companies, 5% are black, despite black people making up 9% of the state’s population. Considering the industry is supposed to factor in the impact of the War on Drugs – where African Americans made up 41% of drug sales arrests in 2014, according to the American Civil Liberties Union – the number of black people involved in the industry behind its goals.

Regulations step in

While the CCC promulgates regulations and guidance meant to prioritize diversity and equal access, some companies do not seem to care, said CCC Commissioner Shaleen Title.

But those who disingenuously developed diversity plans, or who half-heartedly followed through with them may be in for a rude awakening when it comes time to submit progress reports demonstrating how those plans were implemented, Title said.

“Some companies might have mistakenly thought all they had to do was hire a consultant to write a sufficient diversity application for their initial application and never think about it again,” Title said in an email interview. “Some companies can’t even do that. We repeatedly get diversity plans listing their goal as ‘Hiring 10% women and/or minorities.’ That’s objectively ridiculous and embarrassing for them.”

Title said cannabis business owners are opening up shop in parts of the state where hiring racially diverse staff members may be difficult because of the area’s demographics. In that situation, employers can focus on other areas where diversity is needed. She said having gender equity is the bare minimum – women live everywhere.

“It makes me furious when I see statistics that nationally, only 38% of cannabis companies have even one woman board member,” Title said. “Massachusetts is doing better than the industry nationally, but that’s a low bar.”

Moving forward, Title said she’d like to see the CCC’s equity program specifically target people of color, women and other marginalized groups, not just communities impacted by the War on Drugs. She highlighted the CCC’s president and executive director penned a letter to the Massachusetts legislature, voicing support for a public loan fund for small cannabis businesses to avoid the problems with financing, and asking municipalities be required to have an equitable local approval process.

“The process of hiring with diversity goals in mind means hiring where all kinds of people can thrive,” Title said. “This is in contrast to determining whether an applicant is a ‘good fit,’ which [is] an outdated concept fraught with unconscious bias.”

Maintaining control

Bradshaw went through the CCC licensing process as an economic empowerment applicant, a program meant to promote equity among cannabis businesses. He was one of the first nine people approved for the program in the state, according to CCC.

Those eligible for the status must meet certain criteria to demonstrate the business is being run by people who have lived or worked with communities disproportionately impacted by the War on Drugs, and/or who are part of those communities themselves. The CCC lists six possible criteria; eligible applicants must meet three.

But the challenges Bradshaw has faced in moving New Dia toward an opening date exceed basic priority applicant eligibility thresholds. A main reason for his two-year wait is because of how hard it is for small cannabis companies to acquire the capital needed to get their businesses off the ground.

Because cannabis remains illegal at the federal level, would-be entrepreneurs are unable to secure traditional bank loans and have to seek funding elsewhere, like private investors and wealthy family and friends. This is a particular challenge for people like Bradshaw who prioritize maintaining majority control of their company.

“A lot of people like myself want to raise funds, but you don't want to lose control of your operations,” he said.

Retaining control is important to many small businesses, but especially to Bradshaw, who is building New Dia with the mission of supporting social justice and equality in the community.

“It took a while… to find investors that were willing to work with us and share that same vision,” Bradshaw said.

Bradshaw retains 95% control of New Dia, which he said is unheard of.

If the state were to reform the Economic Empowerment program to ensure it actually does what it is intended, Bradshaw said there needs to be support for helping its applicants access capital. Specifically, that means pushing through state legislation establishing a Social Equity Loan Fund culled from the cannabis excise tax.

The bill is currently with the state's Senate Ways and Means committee, where it was sent on April 23.

Secondly, Bradshaw said, license applications should be more meaningfully expedited for Economic Empowerment applicants. In other words, he said, if an applicant has all their ducks in a row, they should have their applications processed more quickly. Typically, he said, a would-be business owner needs to collect more capital as time wears on, effectively creating a cycle of challenges ultimately perpetuating themselves.

Medical cannabis barriers

Although adult-use cannabis often takes up a lot of the public conversation, the state’s medical marijuana business is fraught with a range of inequities.

“Very few minorities, women, and veterans make up the medical cannabis license holders,” said Nichole Snow, president and executive director of Massachusetts Patient Advocacy Alliance, in an email.

Unlike for adult-use businesses, the CCC does not compile data on the medical marijuana program, as the medical side was established in 2012 before the CCC’s creation in 2017 and was run by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health before it was transferred under the CCC’s purview.

Massachusetts Patient Advocacy Alliance is pushing for reforms to encourage a more diverse applicant pool for medical cannabis licenses, Snow said.

One of the greatest challenges toward promoting diversity again came back to access to capital. As it stands, medical marijuana companies in Massachusetts must be vertically integrated. This requires new business owners to have significantly more cash on hand when starting operations, because they have to cover everything from growing, manufacturing and selling their products, she said.

MPAA is currently advocating for a state bill to eliminate the vertical integration requirement, as recreational cannabis businesses have no such requirement. The bill was referred to the Senate Ways and Means committee on April 21.

Working toward racial equity in the Massachusetts cannabis industry will require a sustained, multilateral approach, as evidenced by advocates and officials already working in the field. But it will require more than rules and regulations, said Bradshaw.

In his view, it will require not just policymakers, but community members, too, to commit to the effort from the top down.