In the first year after elected officials allowed a statewide moratorium on evictions to lapse, tenants in neighborhoods where a majority of residents are nonwhite were nearly twice as likely to face eviction than renters in mostly white areas, according to a new report.

Housing advocates have long warned that communities of color face disproportionate burdens from housing insecurity, economic instability and the COVID-19 pandemic, and a new analysis published Tuesday put specific figures on the scale of the disparities.

While rolling out the Homes for All Massachusetts report at a virtual event, authors and housing advocates said they want to see the Legislature inject additional funding in emergency rental assistance programs and embrace controversial ideas such as rent control or local property transfer taxes.

“Our takeaway here is that we really have to act now,” said Eric Robsky Huntley, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology lecturer and one of the report’s authors. “Ensuring an equitable recovery is a critical first step toward securing safe and stable homes for all. In the short term, that has to mean that we make sure that critical emergency rental assistance remains available and that sufficient tenant protections are in place to prevent avoidable evictions. But this also requires a longer-term vision.”

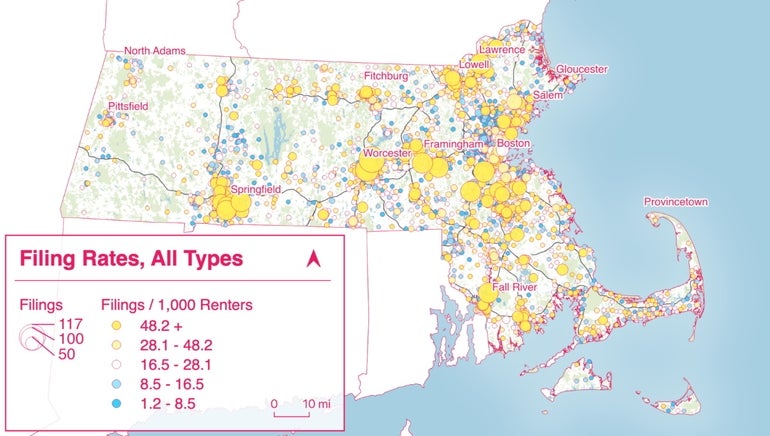

Huntley and other authors representing the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center, Massachusetts Law Reform Institute and Americorps Legal Advocates of Massachusetts examined more than 21,000 evictions filed in state housing courts between Oct. 18, 2020 — when Gov. Charlie Baker and the Legislature allowed the expiration of a temporary state ban on new evictions — and Oct. 30, 2021.

The majority of those cases, about 14,800, involved a tenant’s failure to pay rent and a landlord’s decision to pursue legal action in response.

After comparing eviction cases to population data at the census tract and block group level, authors concluded that “eviction filings have been racialized, gendered, and classed across Massachusetts since the end of the state moratorium.”

In neighborhoods where a majority of residents identify as Black, Latinx, Asian-American or Pacific Islander, or Indigenous, there were 30 evictions filed for every 1,000 renters during the sample period, according to Huntley. Majority-white neighborhoods saw 18.5 evictions filed for every 1,000 renters over the same span.

Those gaps were even larger in more than a dozen individual communities. In Norwood, for example, report authors found 94.59 eviction cases filed in predominantly nonwhite areas per 1,000 residents compared to 15.47 cases filed per 1,000 residents in tracts and blocks with a majority of white residents.

And while Boston often receives a sizable portion of attention around tenant issues, researchers cautioned that the pace of evictions was even more dramatic elsewhere. In Boston, there were 13.08 evictions filed per 1,000 renters in predominantly nonwhite areas; that rate was higher in 11 of the 15 other cities broken out in the report.

“This is a statewide problem and it’s one that is very much not confined to the city of Boston,” Huntley said.

Not all eviction filings end in removal. Landlords often defend the step as necessary to resolve unpaid rent or critical issues with a tenant, while housing advocates caution that a case can tar a renter’s record for years to come even if they ultimately reach an agreement with the property owner.

Real estate and landlord groups have also warned that they endured enormous strain during the pandemic, losing income when tenants are unable to pay rent. In the fall, the Small Property Owners Association told lawmakers that non-corporate owners provide more than half of the state’s rental housing.

Megan Sandel, a physician who serves as co-director of Boston Medical Center’s Grow Clinic for Children, cautioned Tuesday that housing displacement can spiral into years of lingering health effects.

Evictions, she said, “really alter people’s life courses in ways that are unconscionable.”

“In our research and others’, we have seen that even up to five years after an eviction, we’ll see higher rates of maternal depression, higher rates of children being in fair or poor health, having developmental delays, and even having higher rates of being hospitalized,” Sandel, who also serves as a co-lead with Children’s Health Watch, said. “This is not just a one-time impact. This can change the trajectory of a family.”

Other trends the authors flagged include higher rates of evictions filed in areas where more households are headed by single mothers and in neighborhoods where landlords tend to be larger institutions rather than local owners.

“Community is a protective factor, and treating housing as a business is harmful,” said La-Brina Almeida, a MassBudget policy analyst and co-author of the report.

Housing advocates who hosted Tuesday’s event said their focus is trained on a mid-year spending bill due for debate in the Senate on Thursday. The bill (S 2776) as drafted would inject $100 million into the Residential Assistance for Families in Transition program, or RAFT, and several amendments would double that funding amount or increase benefit amounts.

Lawmakers are weighing an injection of additional state dollars into RAFT as the Baker administration prepares to wind down a pandemic-era program built on federal funding, and efforts to pursue broader reforms have not gained traction on Beacon Hill.

The groups also want lawmakers to advance bills allowing cities and towns to implement local rent control — which voters narrowly banned in a 1994 statewide ballot question — as well as real estate transfer fees, tenant options to purchase buildings and other issues that legislative leaders have not named as priorities.

The Legislature and Gov. Charlie Baker allowed a state-level moratorium on most evictions to expire in October 2020, after which the Baker administration and judiciary replaced it with a program aimed at making rental aid and legal help more easily accessible to keep people housed.