With concerns over a lack of affordable housing dominating headlines, communities across the country are starting to reconsider the issue of mandatory parking minimums.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

At first glance, it may seem like common sense that new housing and commercial developments should be required by city planners to have a minimum amount of parking spots to accommodate new residents and customers.

Worcester, like many cities, has zoning bylaws requiring a specific amount of accessory off-street parking for new developments. But with concerns over a lack of affordable housing dominating headlines, communities across the country are starting to reconsider the issue of mandatory parking minimums.

From Anchorage, Alaska to Austin, Texas, cities are starting to eliminate parking minimums after determining these often decades-old zoning requirements are having a detrimental effect on growth and may require more parking than is actually needed.

As Worcester looks to increase its housing stock, a reexamination of parking bylaws is gearing up to be a key aspect of zoning reform.

The rise of the strip mall

In the fight against parking minimums, progressive activists are pushing an agenda of climate reform and eliminating dependency on cars, while conservatives take issue with the idea of bureaucrats putting up potential arbitrary barriers to economic growth, said Tony Jordan, president of the Oregon-based nonprofit Parking Reform Network, which was founded in 1998.

“These are anti-business, anti-economic growth policies. They are a drag on economic development because they reduce flexibility for business owners and entrepreneurs,” he said.

The concept of parking minimums came into prominence around the 1950s, when the post-war automotive boom led to increased concerns about parking in urban areas, said Jordan. Eager to accommodate the rise of the automobile, municipalities tore down disused buildings in urban cores to make way for surface lots or garages.

Planners often took things one step further, implementing zoning ordinances mandating a certain amount of minimum spots for new developments.

“Almost everything built after the ’50s looks like a strip mall or a shopping center, because that was the only thing you could build to be compliant,” he said.

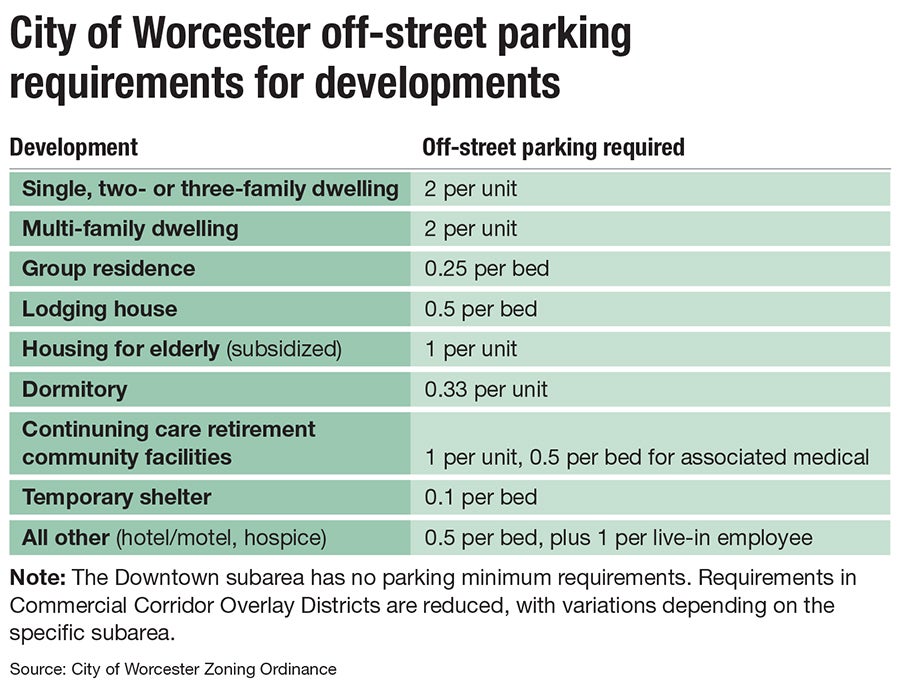

The City of Worcester has 40 different use categories as part of its off-street accessory parking requirements, with rules ranging widely by use, according to the City of Worcester’s zoning ordinance. A manufacturing facility requires a parking spot for every 11,000 square feet of floor space, but a warehouse requires a spot per 13,000 square feet. A heliport requires one spot per 350 square feet of gross floor area, while a marina requires a spot for every four boat slips. A daycare center requires one spot per staff member, but a club or lodge requires 2.5 spots per 350 square feet of floor area. Single or multi-family housing requires two spots per unit, while subsidized retirement housing requires one spot per unit.

“I make jokes that it’s like planners were using crystal balls or rolling dice,” said Jordan, who noted he’s seen minimums for obscure uses like haunted houses or butterfly breeding facilities.

No such thing as free parking

Worcester has a rental vacancy rate of 2.8%, according to U.S. Census estimates, nearly a full percentage point below the nationwide rate. With rental units in short supply, the parking requirements around housing developments can be particularly impactful.

Worcester is a hilly, midsize city lacking the subways, bicycle infrastructure, and other options for transportation available in places like Boston, but the city’s renters do not own as many cars as one might think; 46.2% of renter-occupied units have only one vehicle, and 24.7% of rental units have no vehicles at all, according to the Census.

Worcester’s parking minimums have been a barrier to otherwise non-controversial projects, said Jimmy Kalogeropoulos of RE/MAX Partners - Advance Group in Worcester, who has been in the real estate business for 16 years.

Sitting in his Harding Street office, he pointed out the window to a large building at 22 Waverly St., the former site of St. Casimir’s School sitting on Union Hill and overlooking the Canal District.

The developer who bought the building in December would like to put 24 one-bedroom units into the building, Kalogeropoulos said, but the parking lot associated with the building has 24 spaces, well short of complying with the City’s parking minimums.

He’s not the only one in the city to notice the impact of minimums on housing developments.

“Parking is not free. Requiring more parking than is necessary drives up project costs, and those costs can make an otherwise feasible project infeasible,” Stephen Rolle, commissioner of transportation & mobility for the City of Worcester, said via email. “When projects are constructed, the costs of parking are transferred to tenants whether they are utilizing the parking or not.”

If a solution can’t be found for the Waverly Street project, the developer may have to move forward with building 12 two-bedroom apartments instead, a move Kalogeropoulos said would lead to higher rents and a smaller impact on the city’s housing stock.

“I don’t think the City’s parking requirements are conducive to economic development,” he said.

As the economy shifts, Kalogeropoulos is already seeing financing and loans for new developments will not be as available as years past, meaning the City is going to have to take bolder measures to bolster the housing stock.

“During COVID, banks were very bullish on the economy,” he said. “The next few years are going to be completely different. So what’s the City going to do to set itself apart and continue growing?”

Potential changes

While elected officials and city planners have so far shied away from calling for a complete elimination of parking minimums, smaller reforms have happened, with bolder changes potentially on the horizon.

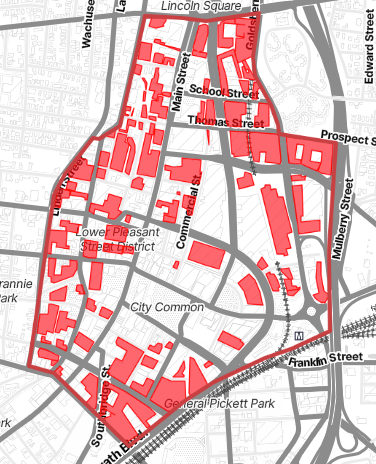

Downtown Worcester already has no parking minimum requirements, and reforms implemented in 2015 led to the creation of Commercial Corridor Overlay Districts, where parking minimums are reduced.

Further change could be on the agenda. The Worcester Now | Next Citywide Plan, a two-year-long planning process aiming to provide a coordinated master plan for development, found the City has had an outsized prioritization toward off-street parking, and land-use patterns are centered around automobile use, according to draft documents produced by the plan’s working group.

"There is a preponderance of evidence across the nation to support the notion that parking minimums have contributed to the lack of housing supply,” Peter Dunn, chief development officer for the City, said via email.

While there seems to be agreement on the need to reform minimums, specific proposals may bring out opposition in some of the city’s older neighborhoods.

“Some residents express concern because there are areas of the city where it can be difficult to find parking. This is generally the case in residential neighborhoods that were developed prior to the automobile, and not a result of current or past zoning,” Rolle said.

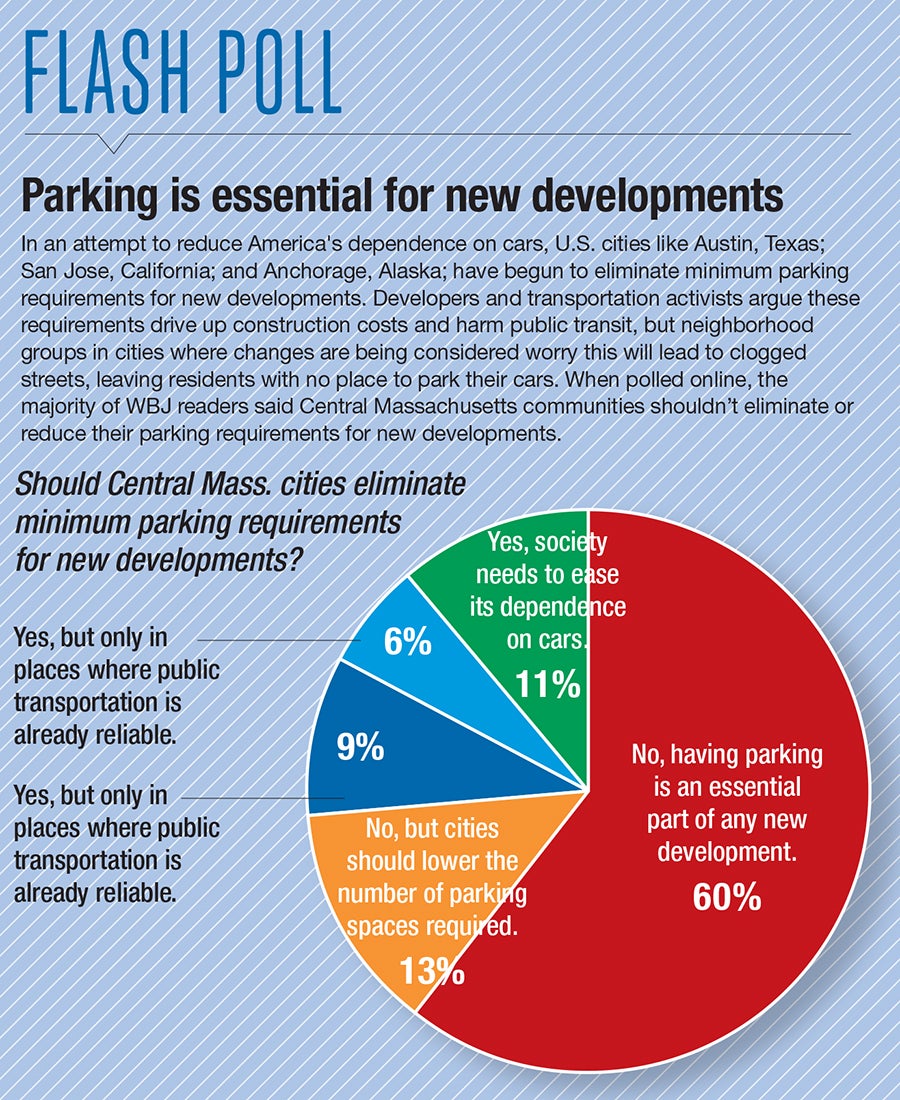

When the average person is asked if developers should be required by officials to designate a minimum amount of parking spots to support a new development, it can seem like it would be obvious to say yes, said Jordan, the parking reform advocate.

But developers are unlikely to build a project if profitability would be prevented by a lack of transportation, and that sort of framing is missing the point, he says.

“This is where we go wrong. We do community surveys asking if we should get rid of parking minimums and people go ‘Hell no!’ without thinking about what they actually mean,” Jordan said. “The questions for the world we live in today are ‘Would you trade parking for walkability? Would you trade parking for affordability?’”