In 2016, 53.6% of Massachusetts voters cast a ballot in favor of legalizing marijuana like alcohol, kicking off the creation of an industry that has so far led to more than $6 billion in sales.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

It may not have been fully legalized until 2016, but marijuana was big business in Central Massachusetts long before that. Despite the fact Massachusetts was the first state to ban marijuana use in the early 1910s, a century of prohibition did little to assuage the appetite for the substance.

Instead, an underground market flourished.

One member of this illicit market was Boey Bertold, whose family’s participation in the marijuana cultivation business dates back generations, much like the moonshiners of yesteryear. In 2007, he was transporting 15 bales of marijuana in Natick when federal, state and local authorities teamed up to arrest him, the result of a six-month investigation. The incident was chronicled by longtime MetroWest Daily News crime reporter Norman Miller with the headline “Pot bust nets 300 pounds.”

It would be one of dozens of similar headlines Miller and others would write as a result of the continuous game of whack-a-mole authorities were playing against growers and traffickers, accomplishing little to stem the flow of cannabis throughout the commonwealth.

Much of that enforcement would be racially biased; an ACLU study in 2016 found Black people were only 8% of the population of Massachusetts, but accounted for 24% of marijuana possession arrests and 41% of sales arrests, despite similar usage rates to whites.

For Bertold, who is white, his run-in with the law meant the possibility of 15 years in prison. He ended up with a three-year sentence.

In prior decades, Bertold’s high-profile arrest would have resulted in a scarlet letter haunting him into the present. Luckily for Bertold, attitudes toward cannabis have changed a lot since WBJ’s founding, when Pew Research Center polling showed national support for legalization hovering at a paltry 17%.

It was 1990 when a group of Boston-area activists founded the Massachusetts Cannabis Reform Coalition, commonly referred to as MassCann, a state affiliate of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws.

“It's very difficult when you take on a cause, especially when you're just a social activist,” said Bill Downing, a stalwart of the state’s cannabis scene stretching back decades and one of the founders of MassCann. “You have no career associated with the work you're doing. It's all just basically hobby work.”

Activists began a campaign starting in the mid-1990s to place nonbinding questions on ballots in Senate and House districts across the state, asking voters if their legislator should support reforming marijuana laws.

Thanks in part to efforts from advocacy groups, public perception shifted, as the nation went from Bill Clinton skirting questions about his own marijuana use in 1992 by saying he “didn’t inhale” to Barack Obama’s candid 2008 admission in his youth he inhaled frequently, because as he put it, “that was the point.”

In Massachusetts, prohibition started going up in smoke the very year of Obama’s admission, when voters decriminalized the substance, eliminating the potential for small-time users to end up behind bars.

In 2012, voters again took action on cannabis, this time legalizing marijuana for medical use.

The law allowed for dispensaries, but thanks to state bureaucracy and fears of action from the federal government the market was slow to develop. Those who were able to open the handful of medical dispensaries needed millions of dollars and a team of lawyers to get to that point, according to Downing, creating an oligopoly with little room for small businesses or entrepreneurs of color.

Opponents of further reform urged for a pause in 2016, but Massachusetts kept blazing ahead, as 53.6% of voters cast a ballot in favor of legalizing marijuana like alcohol.

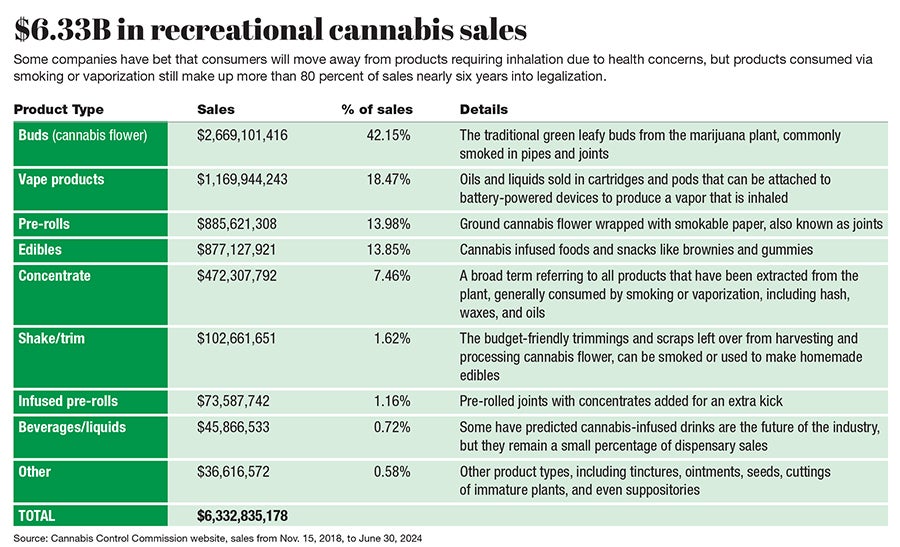

This move kicked off the creation of an industry, leading to more than $6 billion in sales, with Worcester County now being home to more than 80 dispensaries that have received at least a provisional license to operate, according to state data.

For Will Luzier, the campaign manager for the legalization campaign in 2016, the piles of cash created by the industry aren’t surprising.

“We anticipated during the campaign that once the market matured, there would be a billion in yearly sales,” Luzier said. “I think that's been eclipsed, and so it's been successful. Certainly, they've returned a lot of money to the commonwealth and the cities and towns through taxes and fees.”

Prior states to legalize banned people who had cannabis convictions from participating in the now-legal trade. Massachusetts took a different approach, creating pathways for people like Bertold to join this new industry as a means for righting the wrongs committed during the quixotic war on weed, which had a disproportionate impact on low-income communities and resulted in thousands of nonviolent people being thrown in prison.

The state’s social equity efforts helped Bertold and his wife, Lisa Mauriello, to open Paper Crane Cannabis, an outdoor cannabis farm in Hubbardston.

“I think – besides having our kids – being able to start Paper Crane and operate in the cannabis industry in what has been a family business for me for about 65 years, is the best thing to happen to us,” Bertold said. “It’s nice to be able to bring that knowledge and that history and not have to hide it, and to be able to have this amazing company that people love and respect.”

Major talking points of the opposition to legalization – like the potential for skyrocketing teen use – have largely failed to come to fruition, as a 2023 study published in medical journal Clinical Therapeutics found Massachusetts youth were no more likely to use marijuana after legalization.

Instead, a whole new set of unexpected challenges have emerged, many of them stemming back to the strict regulations governing the industry and the Cannabis Control Commission, the Worcester-headquartered agency tasked with enforcing these rules.

The long list of problems emerging from the CCC stretches further than the lines to get into dispensaries during the first few weeks of recreational sales in 2016. Concerns about everything ranging from product safety, equity, worker safety, and the behavior of commission staff have accumulated.

Lawmakers are now considering audits, receivership and other actions to get the CCC’s offices at Union Station back on track. Business owners are now dealing with the falling price per pound of marijuana and social equity companies struggle to compete with large, multi-state cannabis behemoths backed by celebrities, sometimes featuring former CCC employees serving in lobbying roles.

Despite challenges, Luzier is hopeful.

“I think when [CCC officials] said that they were building the plane while they were flying, it was an apt description," he said. “I think eventually they'll start to come around to be supportive of the industry as they should.”

Eric Casey is a staff writer for Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the real estate and manufacturing industries.