In an active shooter situation, the difference between life and death can be a matter of seconds.

When a 911 call gets placed, dispatch operators need to be able to ask the right questions to get information quickly, Dan Jewiss, a retired Connecticut State Police detective, said. Callers need to keep it together enough to tell the dispatcher where the shooter is, so law enforcement can find him or her right away. And police need to arrive and enter the facility as quickly as possible, because studies show the presence of law enforcement alone causes shooters to either barricade, flee, commit suicide, or divert their attention away from the original targets.

“There’s a saying that the body won’t go where the mind has never been, especially if you’re under a ton of stress,” Jewiss said. “It’s a very simple concept that’s backed up by science, that if you simply practice what you would do in that stressful situation that you’re going to be a lot more successful, and that you’re going to do it as quickly as possible.”

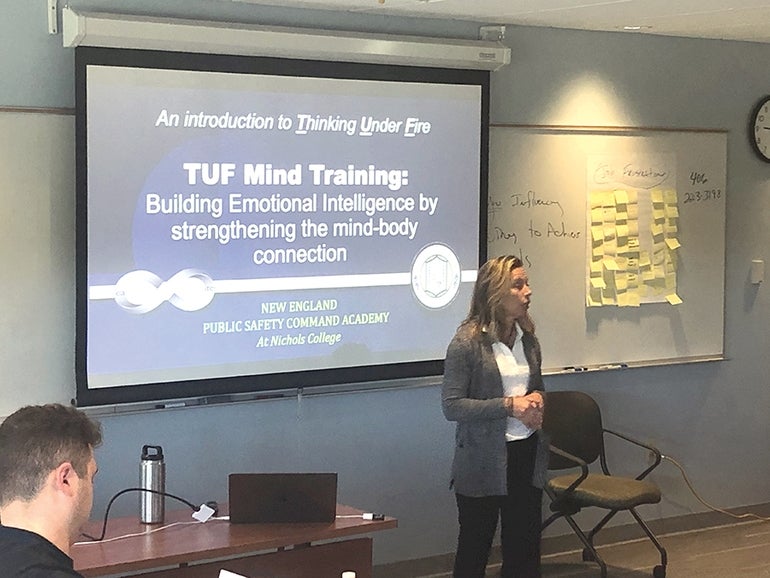

The idea of preparing, and doing simple things that can have life-saving consequences, is just one of the concepts Jewiss discussed as a guest lecturer in a weeklong intensive course at Nichols College in Dudley in May.

Jewiss, who was the lead investigator on the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting case in Connecticut, was a guest speaker at Nichols’ first-ever Public Safety Command Academy, a weeklong program for law enforcement leaders and some students.

The goal of the academy was to train command-level public safety leaders in the principles of what it takes to lead day-to-day and in crisis situations. Six Nichols students and 12 public safety professionals from New England and even one from Montana lived on campus for the duration of the program.

“The more police officers that can hear about challenges and solutions to those challenges, the better police officers we’re going to be,” Tom Stewart, assistant professor of leadership and director of recruitment for Nichols’ master of science in counterterrorism program, said.

Public safety

The command academy was made possible through a partnership between Nichols and Team Training Associates of Connecticut, which provides leadership training to law enforcement agencies throughout the U.S., company President Eric Murray said.

Murray, who has 35 years of experience in public safety, is a military veteran and retired from the Connecticut State Police. He was involved with the Sandy Hook case, which he said inspired him to pursue his doctorate at the University of Hartford. It was there he researched psychological capital as a way to help organizations and officers better manage resiliency and mental health when dealing with traumatic-related stress.

The public safety academy curriculum, he said, centers around leadership and motivation theories, teamwork, and team building. Students did the DiSC (dominance, influence, steadiness, and conscientiousness) personality assessment, a test assigning people different personality types in order to figure out how they should be managed.

Scott Carola, a lieutenant and administrative assistant to the chief at the New Bedford Police Department, said he found the DiSC assessment to be useful as a way to figure out how to manage people. He never received any training on how to lead people when he first became a sergeant in 2006.

“When I was first promoted, I walked into the chief’s office, the secretary handed me a box, inside the box were secondhand badges, sergeant badges that had been used. They asked me to pick out the

two best, which I did, then the chief shook my hand, said, ‘Congratulations,’ and then I was a supervisor. I suspect there were a lot of police officers that had the same thing happen to them,” he said. “But now they’re starting to know the importance of having supervisors trained.”

Jewiss’ lecture, which was about three-and-a-half hours long, focused on his main takeaways from Sandy Hook.

The school system has to be prepared, by making sure things like door locks are checked and maintained on a regular basis. Teachers, students, and staff have to be trained on how to call 911 and what information to give when they reach a dispatcher. It can come down to very small things, Jewiss said, like figuring out which phone you’re going to use to call 911 or where you’re going to hide.

“People always come in with technology and apps and bullet-resistant glass, which is great with physical security, but it’s also very expensive a lot of times,” Jewiss said. “So the concepts that we talk about – information is needed, and how to call it in – it’s just human behavior that you’re talking about, so it’s fairly inexpensive. It’s training your personnel, and it’s a skill they have for life.”

Another important part of the training is mindfulness, Murray said. Students were taught self-regulation techniques like meditation and focus and attention practices. By self-regulating, he said, officers can be intentional in how they respond to interactions with the public and with co-workers rather than reactive. Implicit bias training, including racial bias, is an important component of this as well, he said.

“By understanding implicit biases, we can start to self-regulate biases, and that self awareness is a cornerstone of effectiveness,” he said. “We teach them meditative practices, focus and attention practices, to transition them from one incident to another – work to home, home to work, or any transition they might encounter during the day.”

These meditative practices are important to help minimize the long-term after-effects of tragic events, he said. After all, while families of victims certainly experience the most trauma following an incident, a huge tragedy can really impact an entire community, including the law enforcement officials who are involved.

“After the dust settles, it’s important to focus on things you might be aware of that are not readily apparent, certainly for families who are always at the forefront of attention and focus – and rightfully so – but also for first responders who are intimately involved in the investigation,” Murray said.

Nichols curriculum

The six Nichols students who participated in the academy were to roll it into course credit, according to the college.

One of those students was Isaac Blanford, a graduate enrolled in the college’s master of science in counterterrorism through the 4+1 program, which allows students to get their bachelors and masters within five years. After graduating in May, he moved back to his native Fayetteville, N.Y., where he works part time and is in the process of applying to join the New York State Police. Murray is helping him navigate the interview process.

At Nichols, Blanford said, he originally wanted to study law. But he found himself drawn to police work, and counterterrorism specifically.

“It’s amazing to think about how people radicalize themselves based on their surroundings and groups,” Blanford said. “Terrorists need help to do what they do. It’s usually with a group of like-minded radicals. The fact that there’s that much evil out there makes me want to do something to try to change it.”

In his studies at Nichols and through the training, Blanford said he has seen how important leadership and culture are to a law enforcement organization. A broken system at the Minneapolis Police Department led to the use of excessive force in the murder of George Floyd, he said, and response failures caused devastating consequences in the school shooting at Uvalde, Texas.

But now, as he joins law enforcement himself, Blanford said he can study those situations and use what he’s learned to apply to his own future career.

“It was a great four years at Nichols, and it ended with great experience with Eric Murray,” he said.

“It was a great experience, and I’m really excited to get into my career.”