While all races and ethnicities reported some degree of financial strain, the burdens were far from evenly distributed across the state’s population

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Healthcare expenditures throughout Massachusetts soared to $78.1 billion in 2023, averaging $11,153 per resident. The year’s total represented an 8.6% per-capita increase from 2022, according to a report released in March by the Center for Health Information and Analysis.

That rise in healthcare costs is unsustainable and requires bold and systemic solutions, CHIA Executive Director Lauren Peters said in a press release accompanying the report.

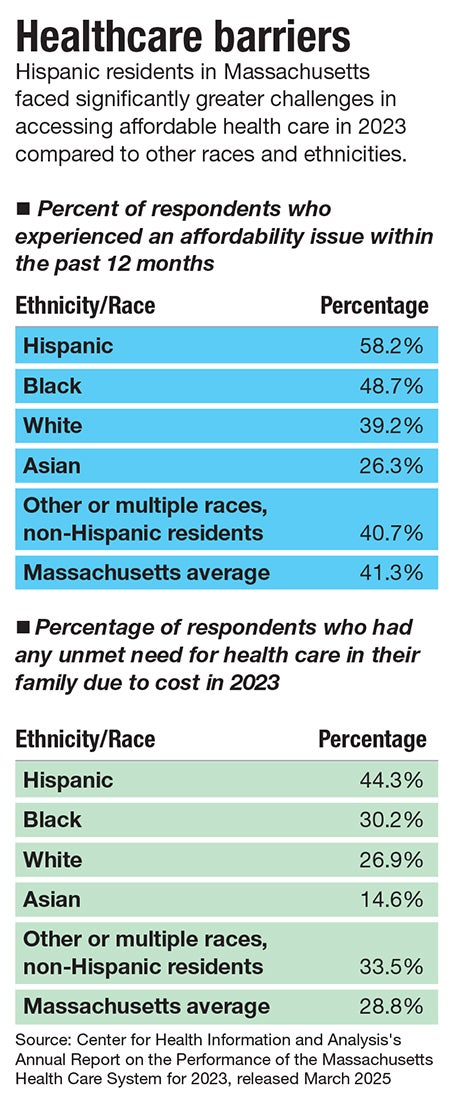

While all races and ethnicities reported some degree of financial strain, the burdens were far from evenly distributed across the state’s population. At 58.2%, more than half of Hispanic respondents reported healthcare affordability issues within the past 12 months, compared to 26.3% of Asian respondents and 39.2% of white respondents. Similar disparities emerged again when respondents were asked about their unmet health needs due to cost.

The barriers to affordable and equitable healthcare for the state’s Latino communities are longstanding. A cohort of Central Massachusetts healthcare and community advocates for years have been working to tackle systemic barriers that keep Latinos from accessing physical and mental healthcare.

“The thought process is, 'We have to go to them,'” said Dr. Matilde, Worcester’s commissioner of health and human services and founder of Worcester nonprofit Latin American Health Alliance.

Addressing inequities through a multi-layered approach, these local leaders are working to close the language gap, advocate for cultural competency, and promote preventive care to best support the region’s Latino community often pushed to the margins.

Economic divide

Low-paying wages throughout the Latino community are a visible disadvantage preventing equitable access to health care, said Castiel.

In 2022, approximately 76% of Worcester County jobs were held by white employees, the same workers who accounted for more than 81% of all higher-wage jobs, according to the North Central Massachusetts Chamber of Commerce. On the other hand, Black and Hispanic/Latino employees made up 17.3% of workers, yet represented more than 25% of all workers who earned less than $35,000 annually.

Systemic issues like these exacerbate an already expensive and flawed healthcare system, said Steve Kerrigan, president and CEO of Edward M. Kennedy Community Health Center in Worcester. Social determinants of health perpetuate disparities in healthcare: limited access to healthy foods, unaffordable housing, discrimination, and chronic diseases all play major roles in making health care less accessible to Latino people.

“Ultimately, it comes to a cost component. And we provide care regardless of people's ability to pay, which we're proud of, but it still can seem like a big challenge to the patients,” said Kerrigan.

Kennedy Health Center has 18 community health workers in Worcester, 12 of whom are Spanish speaking, who work with patients to explore support options to meet their basic needs, including cost of care outside the center, referrals for rent and housing, and employment assistance.

These employees work particularly with the Latino Spanish-speaking population to address specific health disparities, such as increased rates of diabetes and hypertension in the community.

Having Spanish-speaking staff is simply essential to providing effective health care and forging foundational provider-client relationships, said Manny Peña, a program and case manager at Restoration Recovery Center in Fitchburg and former case manager at LAHA.

“The first thing I would advocate for is to have more bilingual people that understand the culture and are willing to work our culture,” he said.

At Kennedy Health Center, about 70% of patients report receiving care better in a language other than English with 61% self-identifying as Hispanic or Latino. While the center’s employees speak a total of 32 different languages, its clientele speaks more than 90, a key reason behind the nonprofit spending about $1.5 million on interpreter services every year, funds that are not reimbursable through the healthcare system

“We prioritize delivering culturally and linguistically competent care at our health center, but there are fewer options and fewer providers who might offer care in someone's primary language,” said Kerrigan.

Navigating the system

Central Massachusetts has places like the Kennedy Health Center to provide care regardless of the patient’s ability to pay; but those options are few and far between, and doing the work to obtain health insurance can often be an uphill battle.

In his past work at LAHA and his current work at Restoration Recovery Center supporting clients living with substance use disorder, Peña is no stranger to the levels of bureaucracy in the Massachusetts healthcare system.

“It's a long process. It's a tedious, annoying process,” said Peña.

As he works to coordinate calls between his clients and MassHealth workers, he is often caught between a rock and a hard place: He’s often trying to convince his patients of the importance of health care, an often-times hard sell to people actively engaging in drug use, while trying to convince the MassHealth worker to let him speak on their behalf.

“I'm trying to convince them at the same time while advocating for them with MassHealth, and [MassHealth puts] barriers by not wanting to speak with me unless the person gives them the okay,” he said.

In order to bypass these hurdles, Peña is looking to become a certified application counselor, a volunteer position helping people enroll in MassHealth and the Massachusetts Health Connector.

With insurance like MassHealth or without, Latino individuals in Central Massachusetts often forgo preventative physical and mental health screenings because those opportunities are not made open and accessible to their communities, said Castiel.

“There are inequities in health care in the Latino community, and I think that physicians and medical entities need to understand that, and we need to develop a system that we can work with the Latino community to create those access points to be able to change those inequities,” she said.

UMass Memorial Health’s Hospital at Home program is a prime example of providing health care within the community, Castiel said. The program brings inpatient levels of care into the home for patients who would otherwise need to be staying in the hospital.

"It's incredibly important to bring care into the home and into their culture, and understanding that piece, I think people do better,” said Castiel.

Cultural connection

“I hate to say this, but somebody's got to say it: Have more Latino people working with more Latinos,” said Peña.

He’s witnessed firsthand a hesitancy from others to work with Latino patients, who then start to look for reasons to not follow through with their care.

There is a culture within the Latino community that emphasizes self sufficiency, leading many to not want to take support.

“We're taught not to ask for help,” said Peña. “Sometimes our Latino pride, it stops us from seeking better.”

Those who don’t understand that aspect of the culture can be quick to wash their hands of a situation if the patient says they don’t need help, he said.

This is where cultural competency becomes critical, he said. A provider who recognizes this dynamic can push back at that mentality and put more effort into providing a space for their Latino clients to be more accepting of support.

“The first thing I tell my people is, ‘Listen, I know that we're taught that we don't ask for help, we don't cry, that bullshit. We're human beings just like everybody else. We cry, we feel, we hurt. I'm here for you. What do you need?’” said Peña.

Mica Kanner-Mascolo is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the healthcare and diversity, equity, and inclusion industries.