For much of its 300-year history, Worcester has been anti-labor, making it harder to organize and fight strict company rules.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Drives for worker unionization seem to be in vogue.

In Worcester, new unionization drives can be seen at places that only a few years ago would have been thought untenable, such as the Starbucks located on East Central Street and among physician residents at UMass Medical School. More established unions in the city have made headlines, such as when members of the Massachusetts Nurses Association striked for more than 300 days in 2021 and 2022 against Saint Vincent Hospital.

But looking back at the 300 years of Worcester’s history, unions have faced an uphill battle.

Anti-labor history

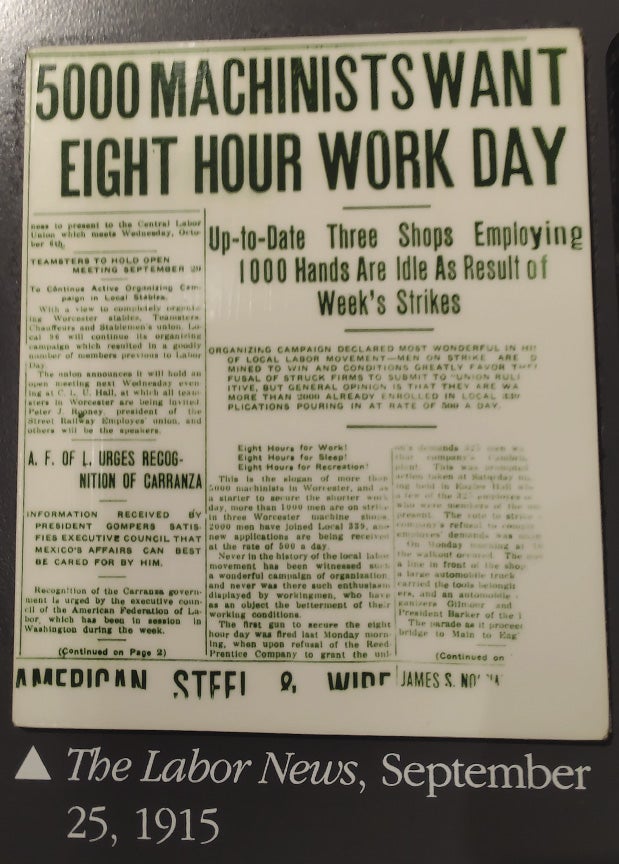

Despite being a U.S. manufacturing hub during the period of industrialization, union efforts in the city faced stiff opposition from both company leaders and the local press, said James Hanlan, a professor at Worcester Polytechnic Institute who specializes in urban and labor history.

“Worcester manufacturers were particularly anti-labor,” said Hanlan. “You had the Worcester County Employment Service, which was run by Donald Tulloch, on a building in Front Street across from city hall, and on the other side you had the Telegram & Gazette, which was run by Harry Stoddard, who was president of Wyman-Gordon. So there were two anti-labor groups, if you will, watching over everything in the city.”

Tulloch would use his employment agency to ensure anyone affiliated with labor organizing would be denied for the city’s largest employers, while Stoddard would use his newspaper to push anti-union views onto the populace, Hanlan said.

The result was Worcester having much less union representation than other manufacturing hubs around New England, like Boston and Providence, said Hanlan.

It wasn’t all bad for the workers of Worcester. Unlike other manufacturing hubs of New England, which specialized in textiles, Worcester focused on parts for machinery, meaning workers had to be more skilled and subsequently were often paid higher wages.

However, without proper union representation, workers were often powerless to go against demands of their employers. Matthew Whittall, owner of the carpeting mills in the south of Worcester, for example, required all of his employees to attend church services on Sunday.

“It was a strictly paternalistic organization,” said Hanlan. “Can you imagine a union trying to negotiate rules about having to go to church?”

Post-war demands

A turning point for workers in Worcester was the outbreak of World War II, which set off a manufacturing craze in the United States in order to support the war effort, as well as help rebuild destroyed nations in its aftermath.

“It’s simple supply and demand,” said Nick Anastasopoulos, a labor and employment attorney for law firm Mirick O’Connell in Worcester. “The world was in shambles and needed to be rebuilt, and we were the ones doing it. Unions could come in because they had gotten a foothold in some of these industries. If they needed a dollar raise, the employer could do it because there was no global competition like there is today.”

The post-World War II rebuilding was a boon for Worcester’s economy.

Yet, as the world was rebuilt, economies became more globally linked and labor ultimately began being outsourced overseas, where it was cheaper, and many of the iconic manufacturers that had defined Worcester’s economy shuttered, said Anastasopoulos.

Union membership in Massachusetts, as with the rest of the country, went into decline. From 1983 to 2021, the percent of U.S. workers dropped from 20.1% to 10.3%, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In Massachusetts, where the percentage of the unionized workforce has been higher than the national average over the past two decades, union membership dropped from a post-millennium high of 16.6% in 2009 to 12.6% in 2021, according to BLS.

A small resurgence

However, events of the last several years have led to a reemergence of interest and support in forming and joining unions, Anastasopoulos said. The COVID-19 pandemic led to initial mass layoffs across various sectors of the economy, and employers have struggled to build back their workforces amid the Great Resignation, where employees are leaving their jobs more frequently, seeking better compensation and working conditions.

The National Labor Relations Board, under the administration of President Joe Biden, is much more favorable to unions than it has been under previous administrations, Anastasopoulos said. The new demand for workers in U.S. companies means unions have more of an edge in the city than they did over the past several decades.

“We’re back again at this concept of supply-and-demand competition, with all sorts of colleges and universities, and we have a lot of tech and life sciences industries,” Anastasopoulos said. “But younger generations entering the workforce now use unions in a much different way than someone a little bit older than me would.”

Whereas a union member in the past would be thought of as a company man and likely stay at the same place of employment, workers are unionizing at places where employment is thought of as more temporary, like Starbucks or physician residents, Anastasopoulos said.

Union members use their organizing efforts to push for social issues, like affirming transgender rights or fighting climate change, he said.

Americans approval of labor unions is at a six-decade high, according to a 2021 poll from national data firm Gallup. Last year, 68% of the nation had a favorable opinion of unions, up three percentage points from the year prior and the highest level since it was 71% in 1965.

“People are viewing unions in a much more positive way,” Anastasopoulos said. “It’s a better educated, sometimes highly educated workforce. You see it in Silicon Valley, and now you’re starting to see it here too.”