For more than a month and a half, Saint Vincent Hospital’s administration and hundreds of nurses have been locked in a tense strike over staffing levels.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

For more than a month and a half, Saint Vincent Hospital’s administration and hundreds of nurses have been locked in a tense strike over staffing levels.

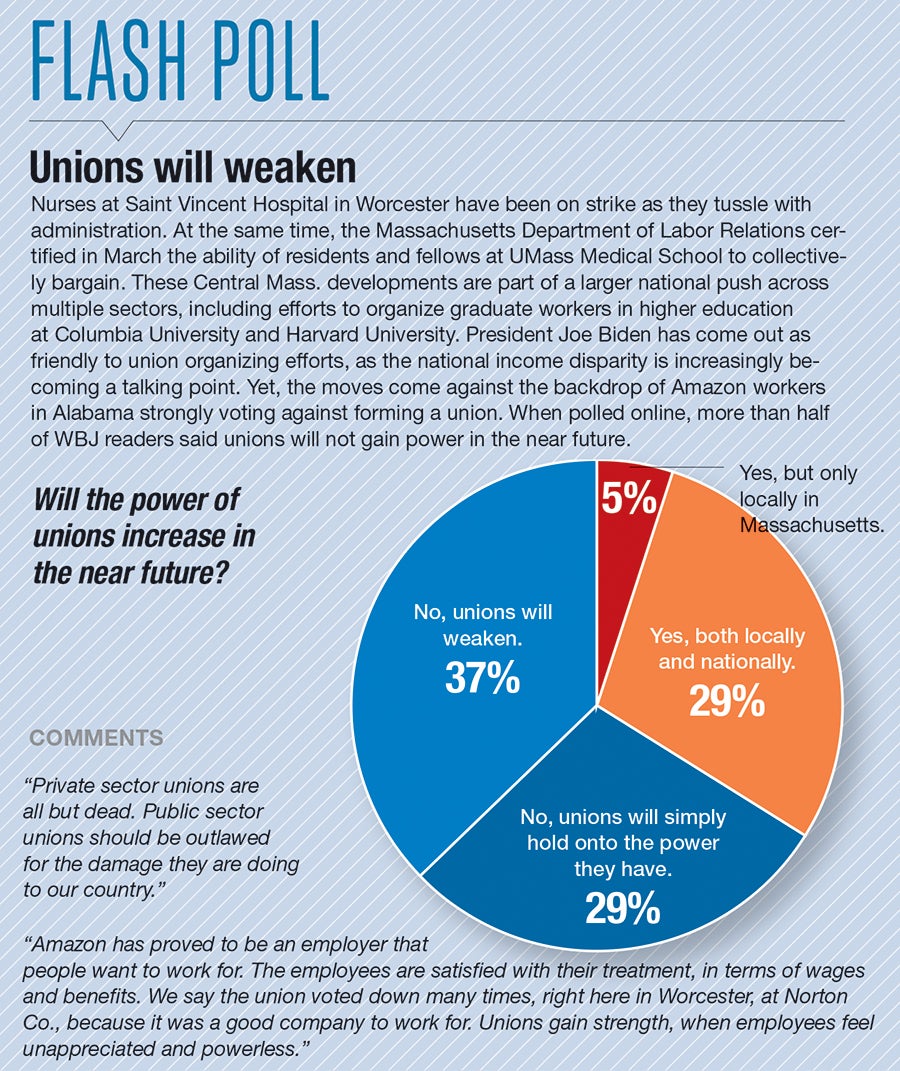

The standoff comes at a crossroads time for unions: their number of members has been on a steady decline for decades, and a high-profile unionization vote among Amazon warehouse workers in Alabama was voted down in early April.

At the same time, unions have gained strength at two other healthcare spots in Central Massachusetts: UMass Medical School in Worcester and Milford Regional Medical Center. The federal government has two strong union backers in President Joe Biden and Labor Secretary Marty Walsh, the former Boston mayor.

“What’s interesting about right now is that there’s a pervasive sense of new organizing,” said Tom Juravich, a labor professor at UMass Amherst. “It feels like a new era for interest in unions.”

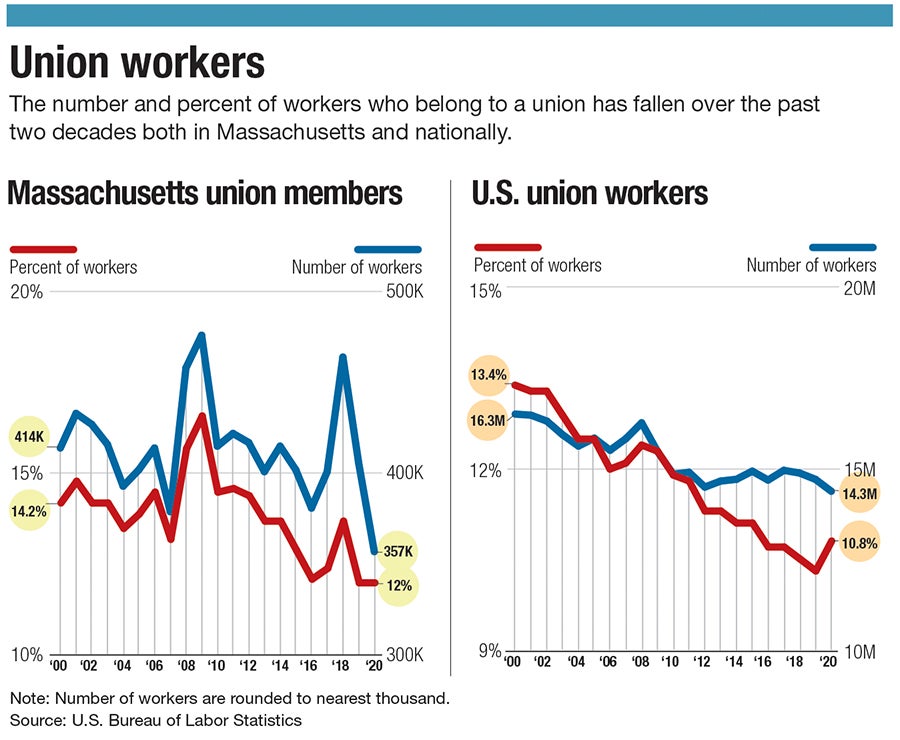

A turnaround in the fortunes of unions would be a long time coming. Union workers have been on the wane for years, both in Massachusetts and nationally.

In the past two decades, the number of Massachusetts workers who belong to a union fell by 14%, even as the number of total workers grew during that time by 4%, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Nationally, union workers have dropped in number by 13% while the total number of workers has jumped almost 7%.

Effects of a shifting economy

Labor experts attributed the disappearance of union labor to a few causes.

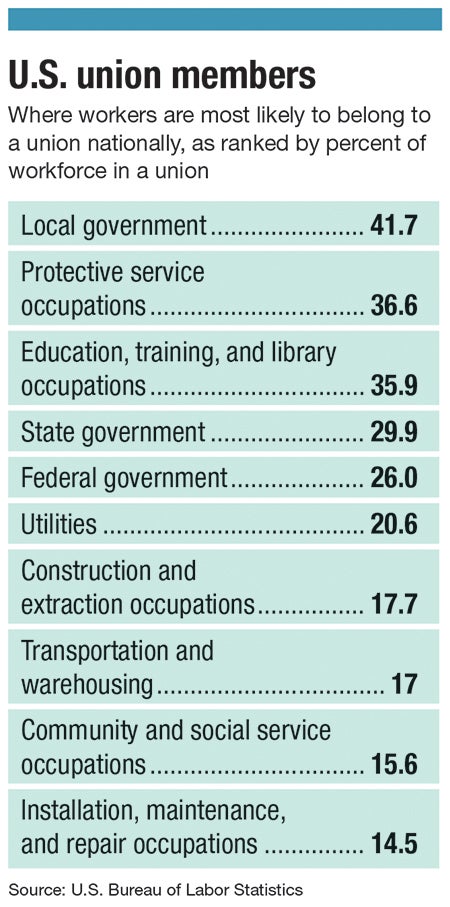

For one, the automakers, steel factories and other jobs that long ago made up the backbone of organized labor are largely gone. Where automakers do have plants, many are in the South, where labor is cheaper and support for unions is lower.

Exacerbating that has been federal and state laws experts said have weakened unions. More than half the states, though not Massachusetts, have passed right-to-work laws, which, among other aspects, don’t require employees to pay union dues.

Experts find employers typically less friendly to working with unions on bargaining.

“Employers are more and more hostile to unions in recent decades,” said Ruth Milkman, a professor of sociology and labor at the City University of New York.

Into those diverging trends comes the Saint Vincent strike, which comes down mainly to how many patients a nurse is assigned to during a shift.

The Massachusetts Nurses Association says the hospital gives nurses too many patients to take care of, sacrificing safety and the quality of care. The union says Saint Vincent has the finances to increase staffing – its parent company, the for-profit Tenet Healthcare in Dallas, had $414 million in profit on more than $4 billion in net operating revenue in the fourth quarter. Saint Vincent ended its most recent fiscal year with a nearly $74-million net surplus, a 14.2% profit margin.

Saint Vincent, for its part, says that staffing levels are safe and in line with industry counterparts. The two sides have yet to sit down for negotiations since the strike began March 8, and they’ve exchanged sharp barbs and allegations of bad faith in the weeks since.

In the meantime, two other healthcare-related sites in Central Massachusetts have shown continued union strength in the past few months.

Nearly 57% of registered nurses at Milford Regional Medical Center voted in February to join the Massachusetts Nurses Association. A few weeks later in early March, more than 600 doctors in training at UMass Medical School voted to join the Committee of Interns and Residents, a nationwide group of 17,000 resident physicians and fellows.

The length of the Saint Vincent strike surprised many experts, who said such standoffs are usually settled more quickly. While not speaking about Saint Vincent in particular, experts said such a relatively long strike can tend to favor an employer with deeper pockets than striking workers with bills to pay.

“The longer it goes on, the more it favors the owners,” said Leonard Samborowski, a management professor at Nichols College in Dudley.

Potential changes ahead

No matter the outcome of the Saint Vincent strike, which hasn’t gained much broader news coverage, experts said there could be a resurgence of sorts for organized labor, particularly with widening financial inequality, rising public approval, and a pro-union federal administration.

“There’s a good chance that unions may see a bit of a bounce,” said David Gulley, an economics professor at Bentley University in Waltham.

A union rebound would be a huge accomplishment after such a long period of decline, Gulley said, especially given legal changes and some declining political power.

Rising public support – 65% as of last summer, according to Gallup – can play a substantial role, said Megan Way, an economics professor at Babson College in Wellesley. That’s because unions need political support, which stems from voters.

In Saint Vincent’s case, striking nurses have gotten support from three members of the state’s Congressional delegation – U.S. Rep. Jim McGovern and Senators Elizabeth Warren and Edward Markey – as well as Attorney General Maura Healey, all Democrats.

Steven Tolman, the president of the AFL-CIO of Massachusetts, an umbrella union group, has seen unions’ longtime challenges firsthand. The former state senator was a railroad worker in the early 1970s, and he said he watched as businesses’ increasingly hardline stances toward unions became more common.

Today, he said, unions remain critical for their ability to improve the lives of their working members.

“We are the only ones able to fight inequality,” Tolman said. “If you have a union, you have the right to stand up against injustice, the right to advocate for safer working conditions, and most importantly, the right to good wages.”

The Amazon vote was closely watched nationally in the labor industry, including whether it could signal bigger workplace changes ahead for the e-commerce giant that’s become one of the country’s largest private employers. That follows a California ballot vote last fall in which so-called gig employers such as Uber and Lyft were exempted from classifying drivers as workers, and instead as independent contractors.

Few in the industry expected the failed Amazon effort to be successful – it was stacked against a huge company and not in a geographic union stronghold. But it could be the first effort of what may end up as a series of failed efforts before one is successful, Juravich said.

Legislative help may be on the way.

A bill, the Protecting the Right to Organize, or PRO, Act, would limit employers’ ability to stand in the way of union organizing and strengthen the government’s powers to punish companies violating workers’ rights. It faces a daunting challenge in the Senate, but experts nonetheless see a shift in place.

“It could take some time,” Way said, “but the tide is starting to turn.”