With the population in Massachusetts, and across the country, aging, the demand is growing for all sorts of health services, and as is the need to find people for these jobs.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Think about the jobs of the future, and you might picture robotics engineers or biochemists working on the latest advances in pharmaceuticals.

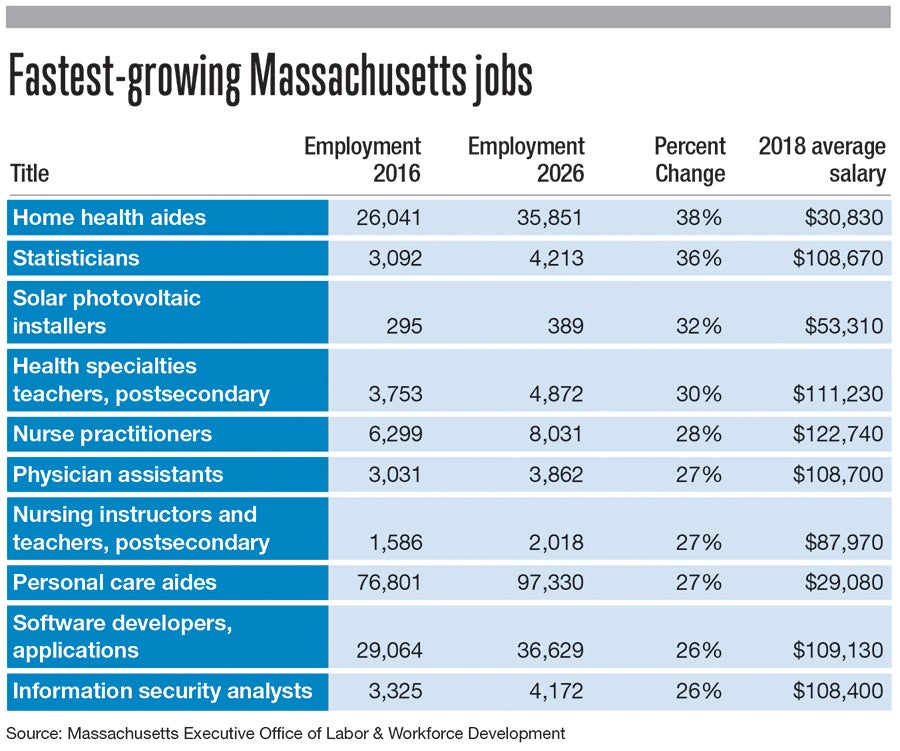

But Massachusetts labor projections suggest, from 2016 to 2026, six of the 10 fastest-growing jobs will be in health care. With the population in Massachusetts, and across the country, aging, the demand is growing for all sorts of health services, and as is the need to find people for these jobs.

The issue is particularly pronounced in home care. The fastest-growing job category over the decade is home health aides who care for disabled, ill, and injured people. Those positions are expected to grow by 38%, or 9,810 jobs. Meanwhile, personal care aides, a similar position involving help with daily tasks but not direct medical care, have the largest growth in total jobs, more than 20,000, a gain of 27%.

Elaine Fluet, president of Gardner-based GVNA Healthcare Inc., said these jobs are hard to fill.

“We have a shortage of individuals willing and able to work as home care aides, and the need is just growing,” Fluet said. “It’s one of the fastest growing areas and one of the most difficult areas to recruit.”

That’s partly because these jobs aren’t highly paid. Home health aides made an average of $30,830 in 2018, and for personal care aides it was $29,080. Fluet said people may choose retail jobs instead just to make enough money to support their families. And, she said, not everyone is cut out for care work.

“They have to be gifted in being able to care for people at the most volatile time of their life,” she said. “The people who work as home health aides are angels day in and day out doing the hard work, really helping people stay in their homes.”

Fluet said GVNA’s wages are largely determined by reimbursement rates set by payers like Medicare, and even clients who pay privately often simply can’t afford to pay more.

As medical technology has advanced, Fluet said, people are more likely to be sent home from the hospital very soon after having a procedure. Meanwhile, many older people prefer to get day-to-day help in their own homes rather than a nursing home. These trends can improve people’s quality of life and reduce overall costs to the health system, but only if enough caregivers are available. So far, Fluet said, GVNA has filled the needs of its clients, but the growing need raises concerns.

“Sometimes there might be a wait time to get care from a home health aide,” she said. “You sort of hold your breath. If you’re somebody who needs it, are you going to stay on your feet, not fall? It is dangerous.”

Practitioners & assistants

Two other professions growing just as fast are nurse practitioners and physician assistants, both projected to increase by more than 27% for a total gain of more than 2,500 positions.

Lauren Katz, administrative chief of advanced practitioners at Worcester-based Reliant Medical Group, said the organization has been increasing its employment of both kinds of medical professionals over the eight years she’s been on the job.

As Central Massachusetts faces a shortage of primary care physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants help fill the gap.

At Reliant, Katz said, primary care doctors now often work in teams with these providers, who can offer many kinds of care traditionally provided by physicians. She said this system works well for providing continuity of care.

“It’s actually better for the patients,” Katz said. “If the physician’s out of the office, the hope is that the nurse practitioner or the physician assistant is there.”

The system helps Reliant serve more patients while creating teams to work together to review cases or lab results.

And Katz said nurse practitioners and physician assistants can take on their own caseloads, and work in specialties as well as in primary care.

Educating healthcare workers

Of course, as demand for highly educated health professionals rises, so does the need for the people doing the educating. The state numbers show positions for postsecondary nursing and health specialties teachers are both on the rise, with a projected growth of more than 1,500 jobs over the decade.

Joan Vitello-Cicciu, dean of the Graduate School of Nursing at UMass Medical School in Worcester, said she just learned the average age of faculty teaching nursing is 65.

“‘Whoa,’ is all I could say,” she said. “Many of us will be retiring in the next 10 years, so there’s going to be a lot of wisdom that goes out.”

To fill those positions, Vitello-Cicciu said, schools need to encourage more nurses to earn either Ph.D.s or doctorates of nursing practice. Both allow them to do scholarly research, and Ph.D.s can perform academic research.

So far, she said, the UMass nursing school has had a relatively easy time filling its openings, unlike some of her colleagues from around the country. She credits her faculty with making hiring and retention easier.

“They are embracing of new people,” she said. “It’s a very strong sense of community here.”

Still, Vitello-Cicciu said, as retirements increase, she’s looking for ways to make sure students continue to learn from teachers who have both academic and clinical experience. One potential method is to encourage long-time nurses with advanced degrees to stay engaged on a very part-time basis even after they’re mostly retired.

“If I was worrying that I was losing a lot of experienced people, I’d ask them to come back and at least teach one course, maybe online,” she said. “We could have them mentor new faculty, coach new faculty.”