Holes in health insurance coverage are causing major disparities, as well as a growing burden on Central Massachusetts healthcare providers.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Now at more than 20% of the city’s population, Worcester’s immigrant community has grown exponentially over the last decade, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, but holes in health insurance coverage are causing major disparities, as well as a growing burden on Central Massachusetts healthcare providers.

In the state of Massachusetts, 30,000 children and young adults under 21 are ineligible for comprehensive health coverage because of their immigration status, according to Boston nonprofit Health Care For All Massachusetts.

More than 1,600 of those kids also have disabilities.

“Even though Massachusetts was one of the first to create safety net programs that cover undocumented kids, other states have actually gone further and included them in their comprehensive Medicaid programs,” said Suzanne Curry, behavioral health policy director at the state's HCFA chapter.

MassHealth, the state’s Medicaid program, covers 340,000 non-citizens, according to the agency.

This includes programs covering pregnant mothers with incomes under 200% of the federal poverty line and non-citizens with permanent resident status.

Still, many individuals do not meet the specific criteria of MassHealth programs, said Curry.

Undocumented children in the state rely on what Curry refers to as cobbled together safety net programs, which include an amalgamation of federally qualified preventative health centers and payment services for acute care.

“There are lots of limits on both the services that are covered and the types of providers you can go to when you look at the different safety net programs that are available,” said Curry, who started her policy work reforming health safety nets before focusing solely on gaining comprehensive care for these at-risk populations.

The Children’s Medical Security Plan, a safety net offered to uninsured children, covers $200 of prescription drugs and 20 mental health visits per year.

“It’s also very confusing for anyone, nevermind families who may have language barriers or other barriers to getting culturally competent care,” Curry said of the Children's Medical Security Plan.

The cost of inequality

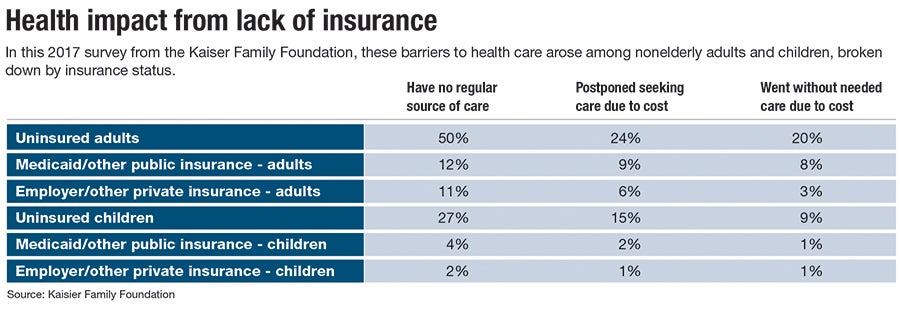

While these programs go a long way in offering important care, disparities in health outcomes persist among immigrants and people of color.

For example, 63% of all dental-related emergency department visits in Massachusetts were from Black or Hispanic/Latinx patients in 2019, according to a report from the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission, demonstrating a disproportionate lack of preventive care access for communities of color, not just for dental health.

“These types of patients are only seen by the system when they are really in need of emergent care,” said Sergio Melgar, chief financial officer of UMass Memorial Health in Worcester, the largest provider in the region. “There has to be something that is terribly wrong.”

Acute care becomes one of the largest operational burdens for the hospital when it spirals into long-term care, he said.

After a patient is treated for an acute or emergency health problem, it is extremely difficult to discharge them from the hospital, knowing the other options unavailable to them, said Melgar.

Long-term rehabilitation facilities are unlikely to take on the financial burden of treating an uninsured patient without reimbursement, leaving hospitals with more than just monetary responsibility.

“Not only are we not getting paid for that, but they’re using up capacity and space that may actually restrict another patient from coming in that does need the care,” he said.

In Worcester, 3.3% of the population does not have health insurance, which is significantly lower than the 9.5% nationally and about the same as the state.

Yet even with a lower uninsured population, local hospitals and providers are facing a significant financial burden.

Of its roughly $3.2 billion in annual revenue, UMass Memorial Health this year will write off $100 million in charges related to patients that don’t have health insurance coverage, said Melgar.

As a nonprofit, the hospital offers care to anyone in need, regardless of coverage. It also receives favorable tax reductions based on the amount of discounted care it provides to uninsured individuals.

The problem is, many uninsured individuals are unwilling to identify as such, which makes it more challenging for the hospital to mark an unpaid bill as charitable. This is especially prevalent among undocumented immigrants, who might be afraid to identify themselves and their status, said John Salzberg, chief revenue officer at UMass Memorial.

In these cases, the hospital goes after the patient, and the cost is typically written off as bad debt, which cuts into 1-2% of UMass Memorial’s revenue, according to Melgar.

A way forward

Curry and her team at HCFA have been working since 2017 to prioritize undocumented children in the fight for equitable healthcare coverage for all kids.

The organization filed a broader healthcare bill for undocumented kids last legislative session, which made it to the Ways and Means Committee in the state Senate.

This session, its bill focuses on gaining insurance for children with disabilities, regardless of immigration status, with hopes of getting the highest-needs children covered as a first priority.

Curry said health disparities revealed by the pandemic have amplified the need for equitable healthcare for immigrants.

“It may be a matter of priority,” she said.

The most recent HCFA bill demanding health care for all disabled children regardless of status is currently in the Senate’s Joint Committee on Healthcare Financing.