While the first five years saw more than $5 billion in sales and hundreds of businesses opening, uncertainty awaits ahead for the next five years.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Nov. 20 marked the five-year anniversary of the first recreational cannabis sale in Massachusetts.

While the first five years saw more than $5 billion in sales and hundreds of businesses opening, uncertainty awaits ahead for the next five years. Companies will now have to attempt to navigate a highly competitive market, the emergence of new license types, and continued efforts to attempt to create pathways into the industry by individuals who have been harmed by the War on Drugs.

Fears of failure

In August 2020, when dispensaries and cultivations were seemingly popping up everywhere, Jason Reposa had a different idea. Legalization ballot initiative supporters campaigned on a message of regulating marijuana like alcohol, but Reposa took things one step further and created a product that looked remarkably like booze.

He did this by starting Good Feels, a Medway-based company manufacturing drinks and beverage enhancers, tincture-like products allowing consumers to infuse any drink or dish.

Drinks made up less than 1% of total product sales by price between November 2022 and November 2023, according to Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission data, but that still equates to $14.7 million of sales, which are expected to grow.

While business is solid for Good Feels, Reposa is worried others might be heading toward closure. Discussions of which companies are failing to pay their vendors is commonplace, and the list seems to be growing by the day, he said.

“Someone came to me and said ‘My daughter is the inventory person at this company. They are about to go under. They can barely pay payroll. Don’t sell to them because you’ll never see that money,’” he said. “We’ve taken that [information], and it’s proved itself out.”

While no one can be sure of specifics, Reposa foresees a situation where the rate of failing businesses increases.

“There will probably be a dozen businesses over a period of a month or two where all of a sudden, like dominoes, they fall,” he said.

After Reposa decided to not pursue a second location for Good Feels, he posted online to see if anyone was interested in buying the license associated with the property. Instead of a flood of offers, he’s received messages from other business owners seeing if he had leads on buyers for their licenses.

“This guy I just spoke to was very exhausted,” Reposa said, “He was just like ‘I want out. This is too painful.’”

Elevated competition

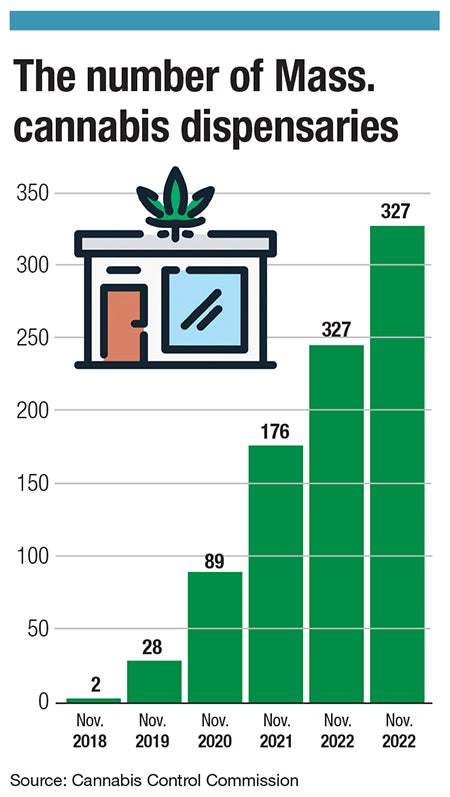

Massachusetts has 327 recreational stores that have been given permission to open, according to CCC data, just a few dozen stores shy of having one store for every one of the state’s 351 municipalities.

Of course, dispensaries aren’t spread evenly across the state. About one third of municipalities banned recreational weed stores from operating within their borders, and those who haven’t often have strict zoning, resulting in stores being clustered together and increasing competition.

In response to concerns over closures, the CCC noted in September only five marijuana retailers have surrendered licenses or let them expire, just 1.6% of dispensaries.

However, these statistics don’t offer the full picture. Companies hold onto their license after they shut down in the hope of finding a buyer, meaning these closures aren’t reflected in statistics. Trulieve, one of the largest cannabis companies in the country with 180+ stores in eight states, formerly operated dispensaries in Worcester, Framingham, and Northampton, but in June, the company announced its withdrawal from Massachusetts.

Despite this, Trulieve continues to be listed on the CCC’s “Find a retailer” page on the agency’s website.

Other dispensaries have seemingly closed for good but appear to maintain licenses, which cost $10,000 to renew.

Uncertain future of equity

Finding funding remains a hurdle for canna-businesses, and this problem is unlikely to disappear soon.

This is particularly true for participants in the state’s social equity program, which is designed to provide pathways into the industry for residents of communities disproportionately harmed by marijuana prohibition.

One step regulators took to help social equity applicants was to set aside cannabis delivery licenses exclusively for participants in the CCC’s social equity program for a period of three years.

While delivery businesses have now been up and running since July 2021, it remains to be seen if they end up playing a larger role in the next five years, as they’ve struggled to tap into an crowded market where consumers are used to driving to the nearest dispensary.

Ruben Seyde is the founder and CEO of Clinton-based Delivered Inc. The company made its first delivery in July. Business has been reasonable, but not enough to overcome the costs of operating, a common problem. He fears more companies will soon start folding.

“There’s definitely going to be more companies that go out of business, and a few of them are going to be delivery companies,” Seyde said, “We need the regulations to loosen up, and we also need the social equity trust fund to open up.”

Seyde is referring to a fund created by lawmakers in 2022 allocating money from cannabis taxes to loans and grants for social equity participants. A functional fund could provide millions to businesses who are in desperate need, but it could be too little, too late.

“The $2-4 million that the state anticipates for the cannabis equity fund this year and the approximately $25 million the agency will disperse in future years doesn't come close to meeting the needs of the moment to undo the historic disadvantages equity businesses face,” said Kevin Gilnack, co-chair of Mass EON, an organization seeking to reduce barriers preventing people of color from becoming participants in the industry.

In addition to the state fund, potential upcoming changes in federal cannabis banking regulations could allow for small cannabis businesses and social equity applicants to access loans from the U.S. Small Business Administration.

Michael Marinaro, founder and CEO of Bada Bloom, a social equity company with plans for a cultivation facility in Tyngsborough, among other ventures, thinks access to these funds could be a gamechanger. He’s hopeful they could provide enough support for craft growers like himself to get a chance to impress consumers with high-quality products, which can be tough to find as cultivators race to grow weed for as cheap as possible.

“We’re starting to see an increase in craft cannabis,” he said. “It’s really looking like consumers are starting to be conscious about what they’re purchasing.”

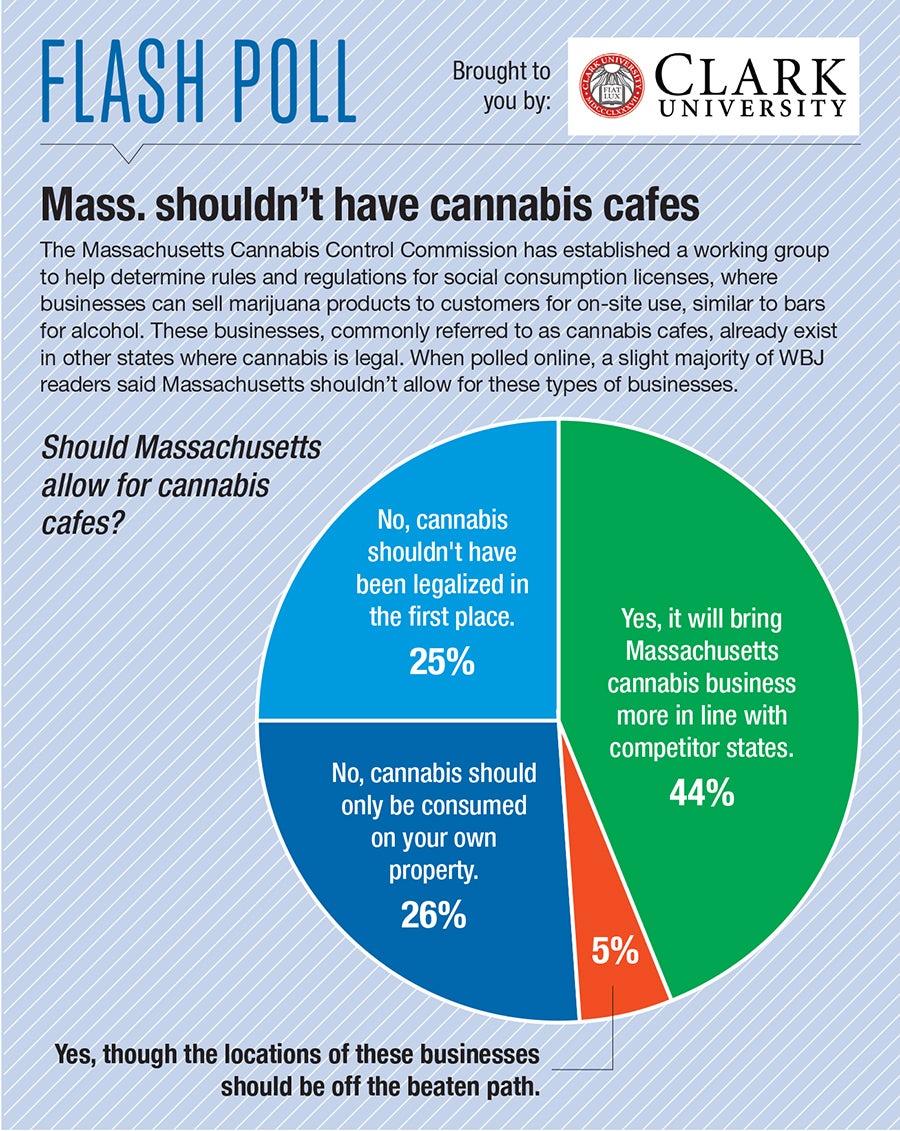

Cannabis cafes

While the state’s attempt to use delivery as a tool for advancing equity has so far been more of a boondoggle than a boom for social equity program participants, the eventual opening of social consumption sites could serve as an additional pathway to make the industry more equitable.

These businesses would offer a place for patrons to buy and consume cannabis, similar to what’s done in a bar with alcohol. The CCC is holding a working group in an attempt to craft regulations to allow state-licensed cafes to open.

Kyle Moon didn’t wait around for the state to create licenses. Instead, he created the Summit Lounge, a bring-your-own-cannabis private consumption lounge on Water Street in Worcester.

Summit opened in 2018, after Moon applied for a smoking bar license with the City of Worcester, without telling government officials exactly what would be smoked.

Moon has constantly tweaked his business plan and is now hosting a regular schedule of events. He said offering experiences going beyond just getting high will be key for these businesses to succeed, something regulators are trying to wrap their heads around as they write rules to balance public safety with business viability.

“You’ve got to constantly be adapting to the shifting market to capture the consumer,” Moon said.

Content with his business, Moon said he’ll have to take a look at the final rules before he considers trying to obtain a state license, noting past proposals would have banned customers from bringing their own cannabis.

“What are you trading for?” he asked. “I’ll have to tell all my customers ‘You can’t bring in your home grow. You have to purchase from me.’”