Toxic masculinity and bro culture are amorphous terms, but in the workplace, they manifest in clear ways.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The craft beer industry was taken by storm in May, after Brienne Allan, a brewer at Notch Brewing in Salem, began sharing stories of sexism, racism, harassment, and other discriminatory incidents alleged to have taken place at breweries across New England and beyond.

The explosion happened the way boiling points like these often do: via social media, as a deluge of whistleblowers and victims shared their experiences working for and tangential to breweries both large and small. The connective tissue between many, if not most, of the alleged incidents, was a strong tendency for brewing workplaces to operate as havens for toxic masculinity, or, more colloquially, bro culture.

In Central Massachusetts, the greatest fallout appears to have taken place at Wormtown Brewery in Worcester, where the bulk of leadership stepped back in May from the company’s daily operations after allegations circulated about discrimination, racial comments, and sexual harassment targeting staff members who were women, members of the LGBTQ community, and/or people of color. The company quickly acknowledged the complaints and promised to institute changes, which were announced in July

Toxic masculinity and bro culture are amorphous terms, but in the workplace, they manifest in clear ways, said Valerie Zolezzi-Wyndham, founder and owner of Promoting Good in Upton, a diversity, equity and inclusion consultancy.

Among those indicators is a proliferation of jokes and comments of sexual nature, about sexuality, about femininity or masculinity, and an understanding those jokes are common and accepted, she said. In some instances where bro culture has taken hold, those kinds of jokes may actually be encouraged.

“Those are the most toxic environments, where you can say that joke out loud in front of the CEO and he laughs along or engages in that behavior,” Zolezzi-Wyndham said.

In more insidious instances, company leadership may not actively participate in these behaviors, but implicitly endorse them by not holding staff accountable when they happen, she said.

Among the anonymous complaints at Wormtown was an allegation sexual harassment was perpetrated by multiple people at the company, including management. One report alleged, upon trying to report harassment issues to one of Wormtown’s owners, the unnamed owner responded he had been sexually harassed by women at the company, too.

Tolerance of oppression can allow it to multiply, Zolezzi-Wyndham said. Allowing sexist comments can make way for allowing homophobic comments and racist comments, too.

One anonymous allegation from Wormtown, made by someone who described themselves as a woman of Asian descent, alleged an employee at the company was sexually harassed by a former colleague more than one time, and accused Wormtown management of falsely claiming pay equity was in place among taproom employees. In reality, the anonymous poster alleged, opportunities for advancement were provided for white staff members.

The same anonymous person claimed a company owner suggested naming a beer after her, using a racist trope as the theoretical beer’s name.

Zero-tolerance for bad behavior

In an industry essentially reliant on entrepreneurial friends coming together to start their own businesses, often growing out of hobbyist brewers rallying their buddies to get into business together, responding to inappropriate behavior can seem at best, daunting, and at worst, in direct opposition to the relaxed vibe most craft brewers try to cultivate.

Running a business with close friends, while not impossible, can produce workplaces where staff speak to each other informally, including in ways not workplace appropriate. This may allow for inappropriate behaviors to permeate, and can create a space where outsiders feel they do not belong, Zolezzi-Wyndham said.

“You’re not really a family,” she said. “It just means rules are loose.”

It is vital, Zolezzi-Wyndham said, to have a zero-tolerance policy for bad behavior.

Healthy, equitable workplaces don’t just fall from the sky; they have to be built.

“Culture has to be very intentional, it shouldn’t be left up to chance,” said Adriana Vaccaro, CEO and founder of Culture Redesigned, a company culture consultancy in Shrewsbury.

Efforts to repair – or even simply establish – a healthy company culture need to come from the top, Vaccaro said, beginning with ownership and the leadership team. And then, they need to be clearly communicated and demonstrated to staff. Oftentimes, well-intentioned employers fail to take that crucial second step. It’s common to encounter disconnects between what leadership believes and employees feel.

In taking on projects, one of the first things Vaccaro does is collect data from employees and present those findings to leadership. In doing so, she can identify discrepancies and guide management toward making changes. These tactics are applicable toward combating toxic masculinity in the workplace.

Both Vaccaro and Zolezzi-Wyndham said these processes require holding negative behavior in the workplace accountable, not sweeping it under the rug.

Righting the wrongs

In response to the anonymous allegations in May, Wormtown announced Managing Partner David Fields would take over as CEO, beginning July 12. That announcement, detailed in an internal memo attributed to Fields and General Manager Scott Metzger, said two employees had been dismissed from the company and one company owner had permanently stepped back from day-to-day involvement with the company, although it did not specify who.

Jay “Digger” Clarke was the only member of Wormtown’s leadership team specifically named in the public allegations in May, and his LinkedIn indicated as of mid-July that he ceased working as a co-owner of Wormtown in March. The brewer declined to say if Clarke was the owner permanently stepping back.

The memo further indicated an internal group had already gathered and made recommendations for improving the company’s diversity, equity and inclusion efforts prior to the allegations surfaced in May. Among the recommendations made by the group: Wormtown should update its reporting policies for instances of harassment and inappropriate work conduct, train staff about appropriate workplace behavior, and improve its human resources options.

The memo said the company is committed to investigating all reports of workplace misconduct, updating the company handbook, and hiring Wormtown's first-ever full-time human resources professional.

“This has been a difficult period of time for all of us, and we continue to be very troubled by the allegations of harassment and discrimination shared on social media and in the press in addition to those overcovered by our own internal processes,” Fields and Metzger said in the announcement. “We want to continue to stress two things – one, harassment and discrimination are not and will never be acceptable, and two, that we are committed to substantial actions to improve our workplace culture.”

The changes at Wormtown were enough to initially assuage the concerns of the Worcester Red Sox, who had partnered with Wormtown as the official beer of the team.

“We take these subjects very seriously, and so I spoke to the owners and was comfortable with the action items they were implementing,” said Rob Crain, WooSox chief revenue officer.

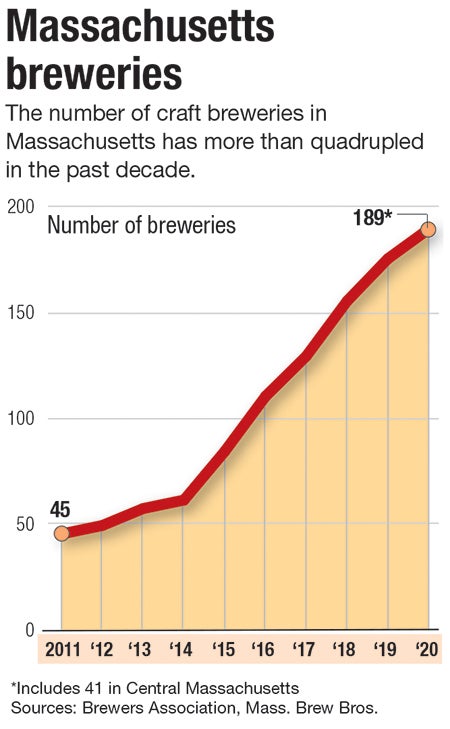

Wormtown is no small actor in the rapidly expanding craft beer industry, as the largest brewery headquartered in Worcester, with 27,913 barrels brewed in 2020. While it waits to be seen whether and to what extent Wormtown and other breweries named in the social media firestorm will either change policies meaningfully or suffer any long-term damages from the reports, attention in the industry has turned toward identifying company cultures erring away from the hypermasculine bro culture.

The tumult has shone a light on a cultural problem in an industry historically dominated by white male business owners and staff, and where a business model centered around down-home approachability has produced workplaces where toxic masculinity can blossom, diverse voices struggle to find recognition, and where other perspectives are silenced. In more casual terms, craft brewing has a bro culture problem. Those fighting say it has to be addressed directly.

Examples to follow

The craft brewing industry, despite the deluge spilling over in May, does contain helpful models for change. One name coming up time and time again in Central Massachusetts is Redemption Rock Brewing Co., located on the same street as Wormtown and founded by four college friends.

At the helm of Redemption is well-known Worcester figure Dani Babineau, the company’s CEO, who in addition to running the brewery sits on the Mass Brewers Guild board and its diversity and inclusion committee.

Redemption has made a name for itself when it comes to diversity and inclusion matters, including in announcing in 2019 its shift to a blind hiring process eschewing the typical resume and cover letter in favor of a questionnaire, and stepping away from the standard tipping model, opting to pay its taproom employees what Babineau has described as a fair wage. The company, a Certified B Corporation whose mission is beyond profits, takes what gratuities it does receive and donates them to a rotating list of area nonprofits.

Although known for its progressive company and personnel policies, one of the first places Babineau points to when discussing beer culture is Maine brewer Allagash Brewing Co.

“They’re kind of who I always look to as … our guiding light as far as breweries who run responsible companies,” Babineau said.

She pointed to the statement the Maine brewer released on May 21, in response to the viral firestorm surrounding industry inequalities and harassment in the industry.

“In the brewing industry, a balance of power is often at play: ownership and in many cases management tends to be male, while females are in more individual contributor roles,” Allagash’s leadership wrote. “Additionally, a general ‘boys will be boys’ attitude present in larger society is exacerbated both by alcohol and the creation of mini-kingdoms where an irreverence for convention can be used to create a ‘rules don’t apply’ culture.”

Babineau said some of the most appealing aspects of working in craft brewing are also what can, when unchecked, make it toxic.

“It’s a pretty glamorous, fun thing to get into, and so people get kind of seduced to that and forget that it’s also about running a business,” Babineau said.

It can be dangerous, she said, when a brewery and/or its leadership develop what she termed a cult of personality – particularly in a field many jump to precisely because they’re looking to escape the typical rigidity within corporate culture.

“[If] they’re problematic individually, you’re going to have a problematic culture,” Babineau said.

Reforming an industry

Katie Stinchon, executive director of the Mass Brewers Guild, said she’s seen breweries face issues with rapid growth.

“I’ve heard far too many stories of brewery owners that [started small and say] ‘We turned around, we had 60 employees, and we thought, 'Man, we really need an HR person in-house, or at least to have someone contracted out,’” Stinchon said.

She’s hoping to help connect local brewers with resources, noting the discourse this year has highlighted for her a gap on the guild’s associate membership list, where there are not currently any HR firms, agencies or specialists.

Stinchon was one of the spokespeople behind the ongoing Hop Forward Equality project, which launched a website in April aimed at providing resources to brewers to help them further their diversity, equity and inclusion work. The kind of work and goals highlighted by Hop Forward, which was originally conceived of as a job fair, Stinchon said, has always been concerned with making sure all voices were heard and included, including people of color, people with disabilities, members of the LGBTQ+ community and, broadly, people who are not men.

The complaints about the industry in May, she said, “more or less just underlines the importance of our work and the importance of bringing in these timely tools and resources right now.”