The brainpower at Central Massachusetts life sciences startup companies is remarkable. But are brains synonymous with business savvy?

It’s an important question for any person with an advanced scientific degree who has dreamed of launching a company: to bring to market a new type of therapy or cure that could serve an unmet medical need, or even save a life.

The people who have graduated from some of the world’s best technological institutions no doubt have the knowledge to develop those products. Whether they can survive the trials of keeping an early-stage company treading water for the several years it takes before they bring them to market is a different story.

Pamela Norton, vice president for industry relations and programs at the state’s Massachusetts Life Sciences Center (MLSC), said a good idea is not necessarily a feasible one. A life sciences industry veteran who now works to connect young companies with the resources they need to grow, Norton said it’s common to see a company run on grant funding for a decade and not progress much from its starting point.

Often, the founders complain that venture capital and seed money to finance major milestones is hard to come by, Norton said. But in many cases, the business’s product doesn’t have what it takes to convince investors.

“We can’t break a thousand hearts telling every single company that,” Norton conceded.

But what Norton does do is encourage startups to go big when it comes to raising money. A common mistake of some of those companies, she said, is raising small amounts of cash that finance large company milestones, such as clinical trials.

“When you raise money to achieve a milestone, you actually create value in your company, making it easier to raise the next (round of) money,” Norton said.

Raising a large amount of private funds was a challenge that Worcester-based Grove Instruments Inc. struggled to meet. The MLSC had provided $750,000 through its Accelerator Loan Program, which provides working capital for high-potential life sciences startups. But MLSC is now a creditor in Grove’s Chapter 7 bankruptcy case, which it filed in April.

MLSC spokesman Angus McQuilken said the agency was enticed to fund Grove because of the technology it was developing, a device that would have been the first non-invasive blood glucose monitor for diabetics. But in the end, McQuilken said Grove was unable to raise enough private money to bring the product to market.

“Any time you are investing in early-stage companies, you do so knowing that some of them will fail, and that’s the risk,” McQuilken said, though he noted that the Accelerator program has a pretty good success rate: Just three of the 32 companies funded since 2009 have ceased operations, and eight have repaid their loans.

‘Proof of concept’ required

For investors to take a company seriously, it must first reach some “proof of concept,” such as pre-clinical or clinical data showing a drug’s efficacy.

Ashland-based Biosurfaces Inc. has reached that point by piecing together federal research funds over the last dozen years. Matthew Phaneuf, who co-founded the company with his wife, Tina, said there were maybe one or two times since launching Biosurfaces when everything was running smoothly; keeping the cash coming in is always in the back of Phaneuf’s mind.

Ready for bigger fish

But now, Biosurfaces is ready to seek venture funding to bring to market its biomedical device, a grafting product meant to mimic the body’s own cell scaffolding for use in artificial arteries that are for patients who need hemodialysis for end-stage kidney disease. Venture funding would finance clinical trials, which Phaneuf hopes will begin next year. He’s also working with a major medical device company, whose identity he asked not be revealed, that’s interested in using Biosurfaces’ technology in products such as sutures. Such a partnership could also potentially fund clinical trials.

Meanwhile, the Phaneufs hired Eugene Anton to lead Biosurfaces’ first spinoff, NuVascular Technologies. Anton is funding NuVascular, the commercial company for the grafting product, called the NuSpun Access Graft. Finding someone like Anton, who has a venture capital background in the biotech space, to run the company was a stroke of luck, Phaneuf said.

“They’re hard to come by,” Anton said. “You need to find that you click; you have the same goals.”

Anton said he was drawn in by the novelty of Biosurfaces’ technology and the potential to help people.

As for the personal expense, Anton is “putting it all in” in hopes of bringing the product to market.

“It’s provided something that’s never been done before. Tens of thousands of people’s lives will be better and will be saved,” Anton said.

Pragmatism pays

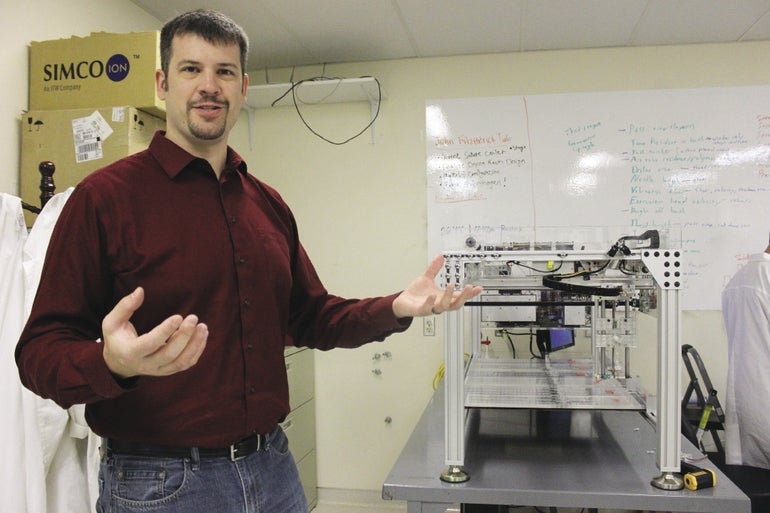

Improving people’s lives is usually a major objective when working at a life sciences startup. But a little pragmatism is also necessary, according to Adam Collette, CEO of VitaThreads LLC, and one of the Worcester-based startups four founders. Collette said a dangerous trap for scientists who launch startups is a lack of focus. They get excited about their technology, but don’t spend enough time researching how it could best be commercialized.

“People get a neat technology and they don’t think enough about the best and easiest way to get it to market,” Collette said.

VitaThreads went through that process, and finally decided that using its fibron technology in sutures designed for plastic surgery was the best way to commercialize it. But three years ago, when VitaThreads launched, the founders had planned to use the technology to deliver stem cells to the heart.

Collette admitted it’s difficult not to “fall in love” with a certain aspect of your product and its potential, especially for people who are so steeped in the science behind it.

“These are folks that are very, very passionate about what they do,” Collette said.

Paul Wotton, CEO of Marlborough-based Ocata Therapeutics, spoke along the same lines when he described the drilling down of the clinical-stage company’s technology over several years to focus primarily on using stem cell therapy technology to treat ophthalmologic diseases that cause blindness.

Today, Ocata is developing stem cell therapy, running ongoing clinical trials in the U.S., the United Kingdom and South Korea. The company may bring its first therapy, designed to treat a juvenile form of macular degeneration, to market in Europe in 2019, Wotton said.

“You can really only be a specialist in one therapeutic area when you’re a company like us,” Wotton said.

An investor’s perspective

In the end, an investor will probably see through the passion and get to the heart of the matter: the return on investment. Patricia Gray, who has worked in angel investing in Central Massachusetts through Westborough-based Boynton Angels but is now primarily associated with Boston-based Mass Medical Angels, said she’s developed her own business plan to determine which ventures she’s interested in and which she’d rather not touch.

Gray looks at three factors: Whether management’s goals include making money for investors; whether the company is savvy about the regulatory process involved in bringing a product to market; and whether the founders take a long view. Often, she said, founders plan to sell their companies before their products enter the market, and they’re not always thinking about the payoff for investors at that point.

“Because people are always pitching,” Gray said. “The question is, ‘Is (the product) really good?’”