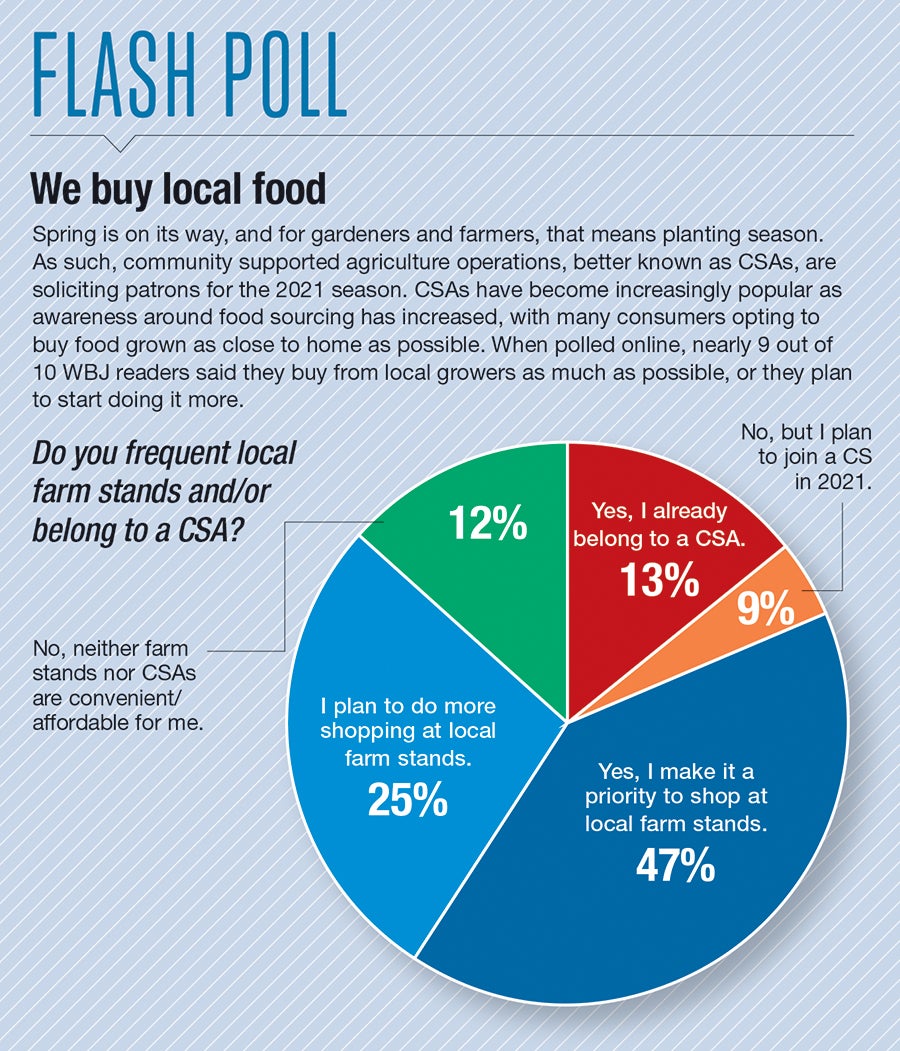

If it seems like farmers markets and CSAs – wherein customers generally pay a farm upfront for produce and/or flower shares to be distributed at regular intervals over the course of the growing season – are increasing in popularity, that’s because they are.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

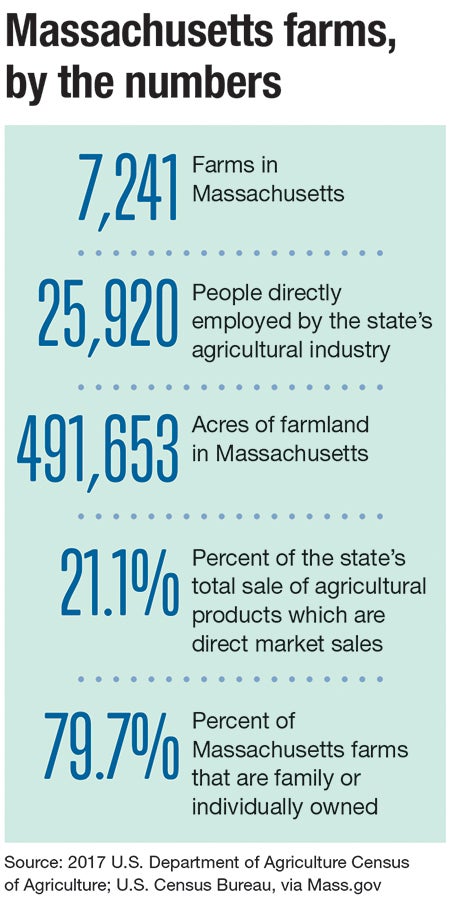

Central Massachusetts has more than 1,700 farms, a fact Mackenzie May, executive director of the nonprofit Central Mass Grown, loves to share.

“Everybody’s reaction is always the same: ‘Wow!’” May said.

Another fact she’s fond of: Worcester County is ranked third in the nation among direct-to-consumer agricultural sales. Farmers in Central Massachusetts, she said, tend to skip wholesaler and third-party buyer options, instead selling directly to customers without any middlemen, often through farmers markets and community supported agriculture, more commonly known as CSAs.

And if it seems like farmers markets and CSAs – wherein customers generally pay a farm upfront for produce and/or flower shares to be distributed at regular intervals over the course of the growing season – are increasing in popularity, that’s because, said May, they are. Bolstered by an aging Millennial workforce drawn to the less conventional ebb and flow of farming life, food justice movements and, yes, by the coronavirus pandemic, farming in Central Massachusetts is having a moment – one the farming community is hoping will last.

In recent decades, farming – much like manufacturing – was recast from an essential industry necessary for societal functioning and into a far-fetched, impracticable career option. Agricultural training was harder to find, the country’s smaller farmers were struggling to make ends meet in the face of deep-pocketed competition and federal fiscal policies that increased interest rates and collapsed grain prices, and Millennials were told they would likely never own property en masse the way their Baby Boomer parents did. White collar, 9-5 office jobs, obtained after a neat four-year degree, became the mold.

But there is a shift happening, according to the local farming community, as consumers grow invested in knowing where their food comes from and, in turn, as some younger people begin to reject the narrative that farming as a career is a pipe dream. And, said May, it has to do with how the younger generations are spending their money.

Millennials, in particular, May said, are spending less on consumer goods which, often manufactured overseas, are less expensive, and instead are reallocating their discretionary spending budget toward purchasing food.

“And that is a wonderful thing,” May said. “There is much more of a shift towards taking the time to go to the farmer's market, to sign up for CSA, to know where your food is coming from, and it’s a societal shift in the buy local movement.”

Free Living

The bulk of Central Massachusetts farms err on the smaller side, said May, producing on small plots ranging from three to 15 acres, or even smaller. One of those is Free Living Farm in Brookfield, run on land leased by Cara Germain and Michael Zueger, both in their early 30s.

Germain, raised in Auburn, and Zueger, originally from Illinois, met in 2013 in California while doing conservation corps work in the state’s national forests and parks. The pair moved around the West and Hawaii taking on different agricultural and farming projects – Zueger’s background is in forestry – before working their way back to the East Coast. In 2018, after training in Maine, the pair dove into their own farm project in Brookfield, where they’ve been ever since.

Together, the pair tend to a one-acre vegetable plot whose produce they sell at the Sturbridge Farmers Market and through their own CSA shares. They are driven, in large part, by strong beliefs around the importance of providing consumers with natural, healthy food.

“I do think there is a movement of young farmers coming in and seeing the potential,” Germain, who studied biology and chemistry at Worcester State University, said. “There’s an interest. There’s a potential. I feel like farming is no longer looked at as a poor man’s job.”

Still, it’s a lot of hard work. With a laugh, Germain remarked they might work as many as 90 hours a week during growing season, with her Saturdays set aside to serve drinks at Timberyard Brewing Co. in East Brookfield – a notably symbiotic relationship, since the brewer both buys their produce and functions as one of their CSA pickup locations. Zueger does forestry, orchard and Christmas tree work as the season calls for.

It’s not for naught. Increased interest in buying local produce combined with a pandemic forcing many to stay as close to home as possible led to a nearly 38% increase in CSA shares last season for Free Living Farm, up to 55 from 40 in 2019. Twelve months later, that growth has been sustained, with the farm retaining its new customers year-to-year.

Although limited by what two sets of hands can do, the duo are discussing growth plans, with hopes to eventually start working with perennial crops, fruit trees and livestock.

Flowers, too

Matthew Lavergne, a 32-year-old farmer who grows flowers on a roughly one-acre parcel of land he leases from his grandfather in Charlton, which he grew up working on, said every day he discovers another new farm in the area roughly the size of his.

“They're just sort of cropping up all over the place, at least, you know, in our immediate area in northern Connecticut and in Central Massachusetts,” Lavergne said. “I mean, who else is going to follow the 50, 60, 70-year-olds who are starting to move away from farming? Somebody got to pick up the mantle.”

This is his third season working Black Moon Flower Farm after spending roughly seven years working at various farms in the Northeast. As with the pair behind Free Living Farm, he went to college – studying photography at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston – and he picks up side jobs, recently working as a lineman on high-tension power lines. Soon, he will work as part-time help on a vegetable farm in Putnam, Conn.

At Black Moon, Lavergne runs flower CSAs and sells vegetable, herb and flower seedlings. The focus, though, is on flowers.

“I do flowers mostly because they’re what interest me, but next to livestock, flowers are actually the highest grossing agricultural product,” he said.

It doesn’t hurt that they photograph well, either.

Moreover, Lavergne said, flowers are less prone to disease and produce more per bed foot, which in turn translates into more money. They require significantly less turnover throughout the season.

Right now, he’s in the process of trialing what types of flowers grow best in the region and when, with the goal of increasing his efficiency as his CSA numbers increase.

In his view, people his age are being drawn to farming life in Central Massachusetts because of growing awareness around flaws in the American societal structure – a conversation growing more mainstream as lights are shone on systemic inequities manifesting around gender, race and income.

“The remedy to that in a lot of big ways is smaller, rural, kind of self-sustainable living,” Lavergne said.

No food wasted

It’s not just Millennials who are concerned about food justice and sustainable living, though. Farmer Tim’s Vegetables, stationed on a 92-acre farm in Dudley, is owned by Tim Carroll of Belmont, who bought the property in 2014 after two decades spent dedicated to his own extensive backyard garden. Carroll, who attended college and graduate school in the 1970s and 1980s, turned to farming a bit later in life.

“My kids were getting into college, and I was getting older; and I thought, ‘What am I going to do?’” Carroll said. “And so I said, you know, I really like this growing food thing.”

Carroll, who still does financial planning consulting for biotechnology companies when not tending to the property, took a farm business planning course and his hunt for farmland led him to Central Massachusetts.

His farm is at roughly five acres of active growspace, and he and his team – which peaks at about eight people during the growing season – are adjusting to a massive increase in demand brought on by the coronavirus pandemic.

In 2019, the farm had 110 CSA members. Last year, that number nearly doubled to 200. This year, Carroll said, he and manager Katie Bekel are aiming for 250. The farm also sells its produce at weekly farm stands in Belmont and, newly this year, in Watertown.

Carroll joked when he first started, his friends and family were his primary patrons because they felt sorry for him. But when his inner circle realized how good the farm’s vegetables were, word spread and transactions increased. Last year, he launched a solidarity fund wherein CSA members are given the opportunity to donate into a pool of money helping pay for shares provided, at a deeply discounted rate, to low-income customers who are given the option of a payment plan.

Full-price CSA members have been exceptionally generous with the fund, said Carroll and Bekel.

Bekel said this makes CSA options more accessible to those customers who cannot afford the investment of paying for their produce in bulk at the beginning of a season.

Farmer Tim’s donates any produce it doesn’t sell at market to Cambridge nonprofit Food For Free, or food pantries in Watertown. If it has an unexpected bumper crop, the farm works with Boston Area Gleaners of Watertown, a nonprofit which harvests surplus food and brings it to people in need.

“We grow it. We want someone to eat it,” Carroll said. “Because frankly, it’s a whole lot of work to grow food. We don't want to throw it away.”