COVID-19 continues to shape the healthcare landscape across Central Massachusetts, as hospitals grapple with soaring costs and staffing shortages.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

COVID-19 continues to shape the healthcare landscape across Central Massachusetts, as hospitals grapple with soaring costs and staffing shortages.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates the national healthcare sector has lost nearly half a million workers since February 2020. In addition, according to Washington, D.C. data group Morning Consult, 18% of healthcare workers have quit since the pandemic began, while 12% have been laid off.

Furthermore, a 2021 poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation in California said about 3 in 10 healthcare workers considered leaving their profession, and about 6 in 10 said pandemic-related stress had harmed their mental health.

Shortages have only worsened during the latest COVID surge, as healthcare workers themselves catch the virus and have to quarantine for several days. At larger hospital systems, hundreds of workers could be affected at a time.

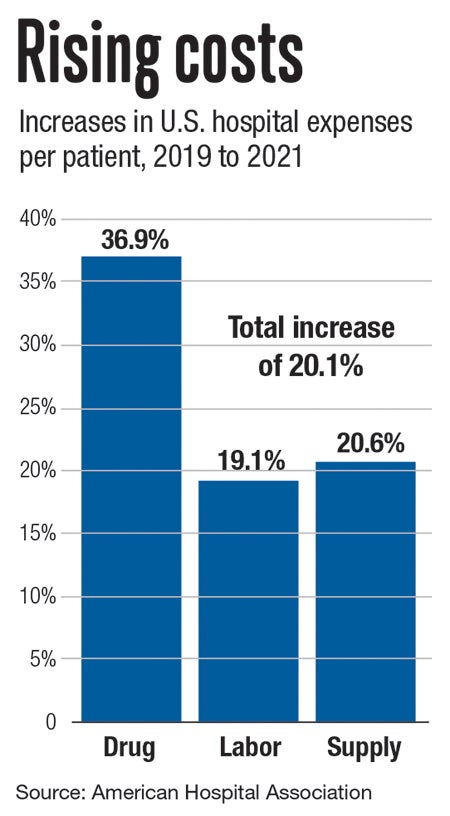

These challenges are hitting hospitals at a time when operating costs are rising exponentially.

According to the American Hospital Association between 2019 and 2021, labor expenses per patient rose 19.1%. Supply costs rose 21% per patient overall, with median drug costs up 37% per patient, and intensive care unit supply costs up 32%.

“The healthcare market is incredibly unforgiving right now,” said Doug Brown, chief administrative officer of UMass Memorial Health in Worcester and president of its community hospitals. “We’re coming out of our fourth phase of COVID-19, and we’re no longer getting federal or state reimbursements. In addition, most hospitals in the country are underwater financially and have had to either shut down services or cut staff.”

A Central Mass. merger

UMass Memorial Health, the largest healthcare system in Central Massachusetts, in May signed a non-binding letter of intent to explore affiliation options with Heywood Healthcare and its facilities in North Central Massachusetts.

Heywood has two hospitals in its system, its main facility in Gardner with 134 beds and Athol Hospital with 25 beds. In addition, Heywood Health operates Heywood Medical Group, the 86-bed Quabbin Retreat for mental health and substance abuse recovery in Petersham.

If the affiliation proposal succeeds, Heywood would join the UMass Memorial System, with its largest facility the UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester with 842 beds.

“It’s a tough time in health care, but particularly if you’re an independent stand-alone hospital,” said Brown. “Heywood, to their credit, realized they could benefit from partnering with a system like UMass. One of the many benefits is increased access to cutting-edge academic resources, research, and recruitment. Patients will have better access to our specialists and world-renowned researchers.”

UMass Memorial Health, which has $2.9 billion in annual revenue, looks to bolster the available healthcare services in the region. Heywood, which has $150 million in annual revenue, would have increased access to capital resources for technology investments, medical equipment, and improved facilities.

Using better technology

One of the major innovations in healthcare during the pandemic is how patient health records are stored and accessed.

EPIC Health Patient Portal, the main electronic medical records system used by UMass Memorial Health, allows patients to monitor and manage health information and see their health charts 24/7 from any computer, smartphone, or tablet.

“EPIC is an expensive platform to implement, so a lot of hospitals can’t afford it,” said Brown of the $700 million UMass spent on the new system. “But it has the ability to really reduce costs. Because when you have a few different medical record systems, not every provider is getting access to the same information. So you can have scenarios where patients will need duplicate tests or have to get seen twice because records were not carried over to another provider. EPIC solves this by creating a main platform for providers.”

Such cost-cutting benefits are just one of the many reasons Heywood is seeking to be the latest hospital to join the UMass Memorial system, which last completed an affiliation in July, with Harrington Healthcare of Southbridge.

The proposed affiliation is expected to take up to one year to complete, following a regulatory review and approval process.

“The pandemic has definitely hit stand-alone hospitals very hard” said Winfield Brown, president & CEO of Heywood Healthcare. “We’re a community hospital, but it can be a struggle to provide for the community when you’re operating under staffing and financial pressures. So by affiliating with the UMass Memorial system, we’re ensuring a more sound future for both our patients and excellent medical providers.”

If UMass and Heywood were to merge then Milford Regional Medical Center will be the only independent hospital in the region.

“It’s about sustainability,” said Winfield Brown. “Affiliating with UMass Memorial provides us a more clear outlook as hospitals are under enormous strain right now.”

A Boston expansion, thwarted

Earlier this year, Mass General Brigham Hospital of Boston withdrew proposals for ambulatory outpatient centers in Westborough and Woburn and to expand an existing facility in Westwood after Mass. Department of Public Health officials would not recommend approval.

According to DPH, acute care hospitals differ from ambulatory outpatient facilities as they must contain a majority of medical-surgical, pediatric, obstetric, and maternity beds for general purpose use. An ambulatory setting might be a non-medical facility like a school or nursing home, but it includes clinics and medical settings typically dealing with non-emergency issues.

MGB had described the proposals as a way to allow its existing patients to receive services closer to home and at a lower cost. But they were scrapped after fierce opposition by organizations banded together as the Coalition to Protect Community Care. These groups included UMass Memorial Health, Wellforce in Boston, the Massachusetts Nurses Association union, Health Care for All, and chambers of commerce representing Worcester, Marlborough, Stoneham, Medford, and Melrose. The coalition argued the plan would hurt local providers financially.

The state’s Health Policy Commission in January told DPH’s determination of need program that MGB’s expansion plans were likely to “drive substantial patient volume and revenue to the higher-cost MGB system, particularly commercially insured volume, and likely away from other lower-cost providers.”

MGB officials disputed the commission’s findings, which differed from a December cost analysis conducted as part of the determination of need process. The December analysis projected the ambulatory care centers would result in a small overall decrease in healthcare spending.

“After learning from the Department of Public Health that our proposal would not be recommended for approval, Mass General Brigham has withdrawn its proposal,” said Anne Klibanski, president and CEO of Mass General Brigham. “Mass General Brigham remains dedicated to transforming care delivery so that our patients receive the right care in the right place at a lower cost.”