In June, Massachusetts Inspector General Jeffrey Shapiro issued a scathing assessment of the state’s Cannabis Control Commission, saying legislators should place the agency in receivership because longstanding disagreements over who held power at the agency had caused turmoil and rendered it rudderless.

In response, CCC leaders rushed to assure lawmakers oversight of the state’s $1.7-billion marijuana industry was continuing normally, even amid a stream of scandals and the firing of the agency’s top official: well-known politico Shannon O’Brien. They argued a new governance charter would soon resolve questions about authority at the commission, and they derided Shapiro’s recommendation as an unnecessarily drastic step based on a limited review.

“As the Legislature intended, we are operating effectively and regulating the industry of cannabis, the number one cash crop in the commonwealth,” then-chair Ava Callender Concepcion wrote in a public letter to legislators. “The commission is on the precipice of writing a new chapter.”

But the commission is hardly ready to turn the page.

Interviews with current and former CCC staffers, along with over a hundred emails and documents provided to WBJ by these staffers and the Massachusetts Office of the Comptroller paint a picture of a dysfunctional agency hollowed out by turnover, bogged down by infighting, plagued by a fuzzy leadership structure, and unable to respond adequately to mounting personnel complaints. CCC leaders are more concerned about appearances and suppressing leaks than addressing systemic issues, all to the detriment of struggling businesses and concerns over consumer protections.

The “inaugural commissioners were policymakers, which is very, very different from some of the commissioners we have now,” said Chief of Research Julie Johnson. “They want to be on the front page [of the newspaper] with a glowing article about how wonderful they are, but they don’t really understand what staff are doing. It seems to only be about optics and not about the reality the staff and industry are experiencing.”

In August, CCC began an investigation into a growing number of staff complaints against Debbie Hilton-Creek, who was hired as the head of human resources as chief people officer and has been serving as acting executive director for more than a year.

CCC denied a request by WBJ to interview Hilton-Creek and the four commissioners, instead issuing a statement on behalf of the entire agency. When WBJ reached out to them individually, three of the commissioners did not respond. Callender Concepcion is on leave and could not be reached.

The problems at CCC have been exacerbated in the past year as Hilton-Creek has served as acting executive director, but CCC employees say the issues will persist once the role is filled as the problems are far more structural. On Monday, the commissioners voted 3-0 to offer David Lakeman the role of executive director, with a salary up to $187,000. Lakeman, who still has to accept the offer, is a former CCC director of government affairs from 2018 to 2020 and most recently the cannabis division manager for the Illinois Department of Agriculture.

Meghan Dube, CCC business operations manager, doesn’t believe replacing or removing Hilton-Creek will lead to any meaningful improvement, given the commissioners above Hilton-Creek failed to respond adequately to the complaints against her.

“They knew the reporting structure was causing problems. None of the commissioners had the integrity to stand up to her at any point. If she’s fired tomorrow, okay, good. But the agency is still in the exact same spot,” Dube said.

These revelations come on the eve of a critical legislative oversight hearing Wednesday, with Beacon Hill lawmakers set to hear testimony on the commission’s governance in the wake of a drama-filled summer culminating in Treasurer Deborah Goldberg firing former commission chair O’Brien for alleged misconduct. O’Brien has denied Goldberg’s claims and fired back with a lawsuit.

Even more drama is playing out behind the scenes, according to current and former staffers, some of whom spoke to WBJ under the condition of anonymity because they fear retribution against their careers and livelihoods for speaking out. (Read about WBJ’s anonymous sourcing policy here.)

They and other employees at the state agency headquartered in Worcester’s Union Station state are party to intense internal conflicts, which involve dueling accusations of workplace misconduct hinging on each employee’s characterization of the interactions in question, complicating their resolution.

Regardless of the merits of each accusation, even employees on opposite sides of such cases agree CCC’s response to their complaints has been ineffectual and protracted, with claims going unaddressed for nearly a year. Others were provided shifting explanations for delays, and even for suspensions.

That inconsistency has fueled the division of the agency’s 140 or so employees into bitter factions, contributing to a toxic culture in which employees say chaos and missed deadlines have become the norm. The division has prompted employees to quit the agency in frustration or urgently seek leave to protect themselves from retaliation after filing complaints.

In response to a WBJ request for comment, CCC Press Secretary Neal McNamara said the agency’s policy is to not comment on specific personnel matters.

CCC “seeks to maintain a fair, equitable workplace, and takes complaints and allegations raised by employees seriously,” McNamara said. The agency “has a duty to … take the necessary time to investigate complaints in fairness to all parties involved.”

He added “public discussions of internal personnel matters may be harmful to the internal investigatory process.”

Reign of terror

CCC’s outside law firm in August hired an additional outside investigator solely to probe complaints by current and former employees against Hilton-Creek, according to emails provided to WBJ by the employees.

Hilton-Creek, a U.S. Army veteran, is accused of fostering a hostile and retaliatory work environment, according to four people familiar with the complaints and documents obtained by WBJ.

When Hilton-Creek was appointed in October 2023 as acting executive director a mere two months after being hired as chief people officer, it marked the start of a reign of terror that shattered already-waning morale, said one former employee who spoke on the condition of anonymity. That former worker recounted employees crying in their offices following harsh exchanges with their new boss, describing an environment in which innocuous clarifying questions were treated as insubordination.

The four CCC commissioners who lead the marijuana agency were aware of complaints about Hilton-Creek, some of them as early as November 2023, but failed to take concrete steps to address them until August, according to CCC emails.

Employees say their attempts to report Hilton-Creek’s behavior were complicated by her dual role as the agency’s acting executive and its top HR official, a status that bumped her salary to $195,000, putting her on track to earn the most of any agency employee in 2024. The employees faulted the commission’s lack of clear procedures for handling such cases.

When the investigator, Springfield-based employment and labor attorney Ed Mitnick, began contacting accusers in September, he quickly found himself inundated with claims.

“I am up to my eyeballs with various complaints from an increasing number of present and former employees making allegations pertaining to Debbie Hilton-Creek,” Mitnick wrote in an email to Dube, the CCC business operations manager, who provided the email to WBJ.

Mitnick, who previously adjudicated workplace disputes as a hearing officer for the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination, added he had an ever-growing file of documentation submitted by Hilton-Creek’s accusers.

Dube, a CCC manager who started at the agency in 2020 when it had 40 employees, said she is making her complaints public despite the risk to her career because she believes the agency is incapable of resolving them without public pressure. She was told by Mitnick his work would take at least three to four months because of the large number of people involved.

Before September, employees who inquired about the status of their allegations against Hilton-Creek said they were given varying explanations for the inaction as months passed.

One former worker was told their report against Hilton-Creek would be investigated only if a sufficient number of other workers also complained about them in exit interviews.

In June, Dube received an email from the human resources department saying there was no timeline for resolving her six-month-old complaint against Hilton-Creek because the agency’s other outside investigator at the time was busy with another, more urgent task: identifying the source of leaks to the press.

“The investigator will be handling multiple issues for the agency, which have all been categorized and assigned a priority,” the email said to Dube, who provided it to WBJ. “Currently, the investigator’s priority is the leaks within the agency … I will reach out to you when your complaints are next in line.”

During a tense June meeting, commissioners voted 3-1 to strip Hilton-Creek of her power over other departments. Then-chair Callender Concepcion said publicly the move would ease Hilton-Creek’s workload so she could prioritize the HR matters she said required some much needed attention, including filling 20 open positions.

The decision alarmed Shapiro, the inspector general, who cited it in his June letter to lawmakers.

“The decentralization of management for the daily operations for an agency that has lacked clear lines of authority does not seem to be in the best interest of the agency’s constituency or the people of the commonwealth,” he wrote.

It is unclear whether the stripping of Hilton-Creek’s authority over other departments was related to the complaints against her. Emails obtained by WBJ suggest conflict-of-interest concerns prompted Callender Concepcion and the agency’s then-general counsel to assume responsibility in January for all complaints regarding Hilton-Creek.

Even so, Dube and others who had complaints against Hilton-Creek have little confidence in the agency’s leaders to make any improvements. Once Mitnick’s investigation into the complaints against her is complete, the agency has no mechanism to implement any suggested changes, Dube said.

Impatient with the commission and mistrustful of how it will handle the results of outside investigations, Dube, Johnson, and another employee who spoke on the condition of anonymity have filed at least a half dozen complaints with MCAD, the Massachusetts State Ethics Commission, the inspector general, and legislators.

Dube was granted leave in October, after she said she could no longer continue reporting to Hilton-Creek.

Because of the multi-sided nature of internal CCC disputes, Johnson said she suspects the charges against Hilton-Creek are exaggerated and calculated to sabotage her attempts at imposing accountability.

Johnson, is currently on medical leave related to the impacts of what she says was mistreatment by other staff. She said the web of accusations and counterclaims among CCC employees was already extensive by the time Hilton-Creek took charge last October, leaving her with an impossible task.

“I do think Debbie came in as very strong with a ton of potential, but she’s just been undermined at every corner,” Johnson said.

Hilton-Creek’s hiring as chief people officer in August 2023 indeed came at a time of disarray and transition for CCC. The agency was facing public concerns over industry safety following the death of a cannabis worker in January 2022. Meanwhile, longtime executive director Shawn Collins was on his way out the door, and incoming chair Shannon O’Brien would soon find herself mired in a controversy over her ownership in a marijuana company.

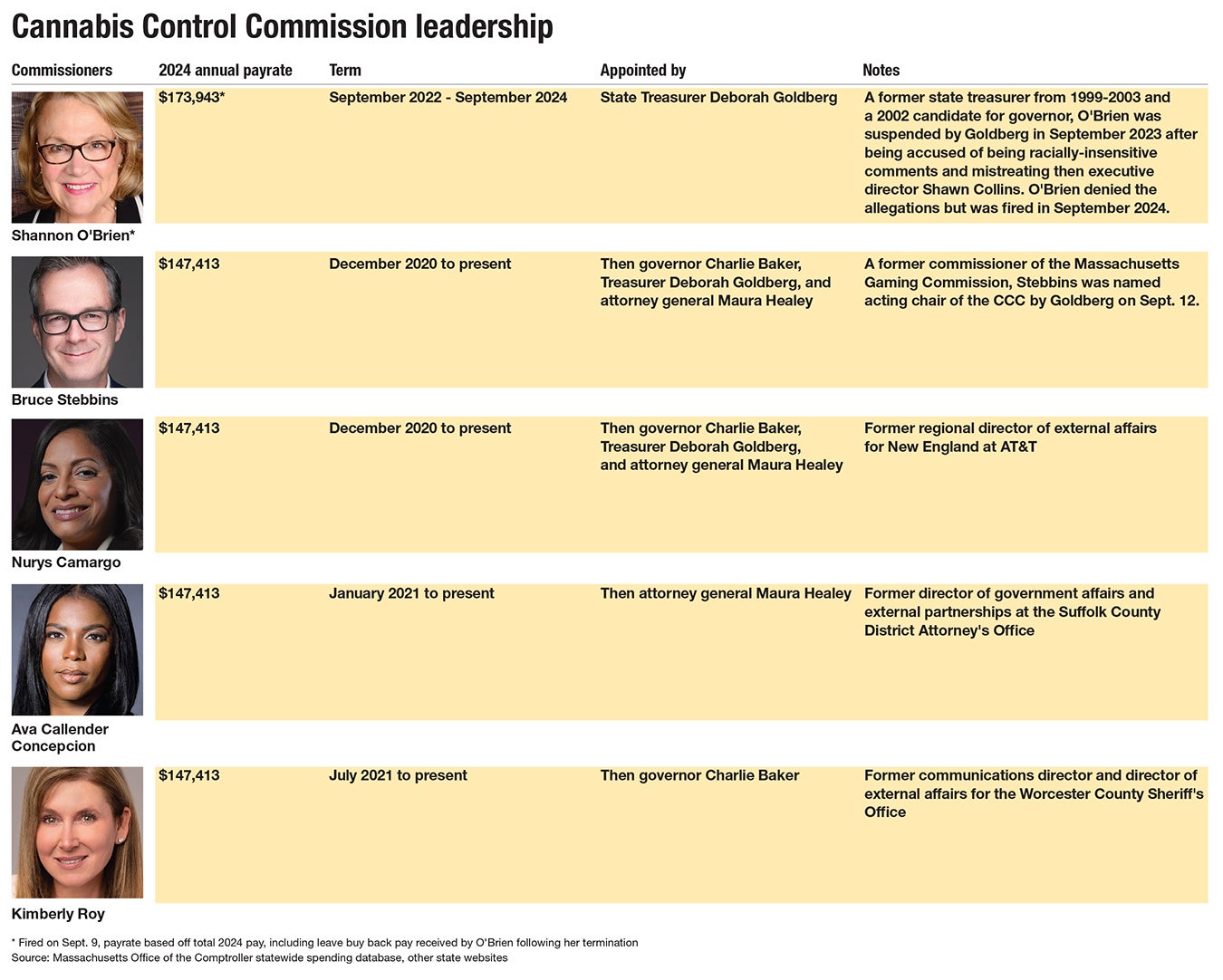

O’Brien would later be suspended and eventually fired by Goldberg, the state treasurer, who appoints the commission’s chair, for allegedly making racially insensitive remarks and other misconduct, including allegedly mishandling a request for parental leave by Collins.

Documents released by O’Brien’s lawyers related to her ongoing legal challenge against Goldberg suggest disagreements over Hilton-Creek’s hiring figured into her clash with Collins, who according to the documents accused O’Brien of meddling in the process of selecting the agency’s next chief people officer. An investigator ultimately dismissed that claim.

Almost immediately after Hilton-Creek was elevated to acting executive director in October, six staff members raised concerns about someone so new to the agency being tapped to lead it. The same day Collins officially announced on Nov. 16 he planned to resign in December, concerned employees requested a meeting with then-acting chair Callender Concepcion, outlining why they felt Hilton-Creek was unprepared for the role.

Hilton-Creek herself has noted deficiencies in the agency’s human resources apparatus, saying at a public meeting in March staff in the department were inexperienced. She urged commissioners to approve the hiring of a new manager to oversee them.

“This is really stressing me out,” Hilton-Creek said after commissioners questioned the need for the position. “I gotta be honest with you … I have a lot of work to do, and I need someone who is going to come in and jump in alongside me and the rest of the staff to get the work done.”

Commissioners ultimately approved the request, but Hilton-Creek reversed course in September, saying at a meeting of the commissioners she had paused hiring for the role to prioritize the search for a new permanent executive director and in order “to make sure that this is exactly the role … that the team is aspiring to bring on.”

Concerns over software contract

Dube’s conflict with commission leadership escalated this summer, after she raised alarms about what she said was discussion by commission managers at a meeting in March to predetermine the outcome of a competitive bid for the agency’s licensing application software.

In a partial recording of the meeting provided to WBJ by Dube, commission Chief Technology and Innovation Officer Paul Clark repeatedly makes clear his intention to select the current contractor, Salem-based JD Software, when the current contract expires next spring.

“How narrowly can we scope the [request for quote] that makes it legal to get us to where we really want to be, which is a continuation of the existing contract?” Clark asked other employees at one point in the meeting.

Clark said he and other CCC employees were not entirely satisfied with the JD Software product, which allows marijuana companies to submit materials to the commission for review and track the status of their applications. Eventually, Clark said the commission intends to replace the software with an all-in-one solution integrated with other agency systems, such as the one used to register medical marijuana patients. But he said the agency was too behind on other work to contemplate effectuating such a change in the near future.

There is no indication that JD Software was aware of the internal discussion about its contract. Clark did not respond to a WBJ request for comment.

Dube alerted a commissioner and other high-ranking officials about the possible violation of rules governing state bids, which generally require a competitive process to ensure taxpayers get the most for their money.

Dube said she was later reprimanded by her supervisor, Chief Financial and Accounting Officer Lisa Schlegel, for sending the email expressing her concerns, saying she should have spoken directly to Clark about the matter instead. Schlegel did not respond to a request for comment.

The CCC legal department acknowledged Dube’s concern about the software contract and advised Dube of her right to contact the state ethics commission. Dube said she notified the Massachusetts Office of the Inspector General, which assigned an investigator to interview her about the allegation.

Carrie Kimball, communications officer for the inspector general, declined to comment on the matter, citing state law requiring the work of the office to remain confidential.

From the CCC’s standpoint, McNamara said the agency was aware of Dube’s concerns over the software contract and the situation had been reviewed. CCC has yet to formally issue a request for bids for when JD Software’s contract expires.

Dube said she is worried further delays will ensure the commission has no option but to select JD Software when the current contract expires in March, essentially rendering the bid noncompetitive anyway.

Rising turnover, rising costs

The chaos inside the commission appears to have sparked an unprecedented wave of turnover.

Since the beginning of 2023, more than 35 employees have left the agency due to termination or resignation, including two chief-level positions and four director-level positions.

The agency’s legal team in particular has seen nine exits in that time, including two general counsels, with former top attorney Kristina Gasson leaving in June after just eight months on the job.

While a handful of positions including the general counsel’s job have been filled by external hires, others remain empty or have been backfilled by promoting current staff without a public, competitive hiring process.

At the same time, the agency has spent significant amounts of time and money trying to resolve seemingly intractable disagreements about how much authority commissioners have over the executive director and staff.

“The fact that we actually have an agency that is disputing the oversight of its commissioners … I think it’s a joke,” said state Sen. Michael Moore (D-Millbury), who has emerged as a prominent critic of the commission. “It’s pretty common sense that the commissioners are put in as the overseers of the agency. They appointment the executive director. That shows to me that that’s the chain of command … it’s been a waste of taxpayers’ dollars.”

The commission voted in April 2022 to begin the process of drafting a governance charter to clarify those questions, and in June of that year hired Brookline-based mediator Susan Podziba to guide the closed-door discussions.

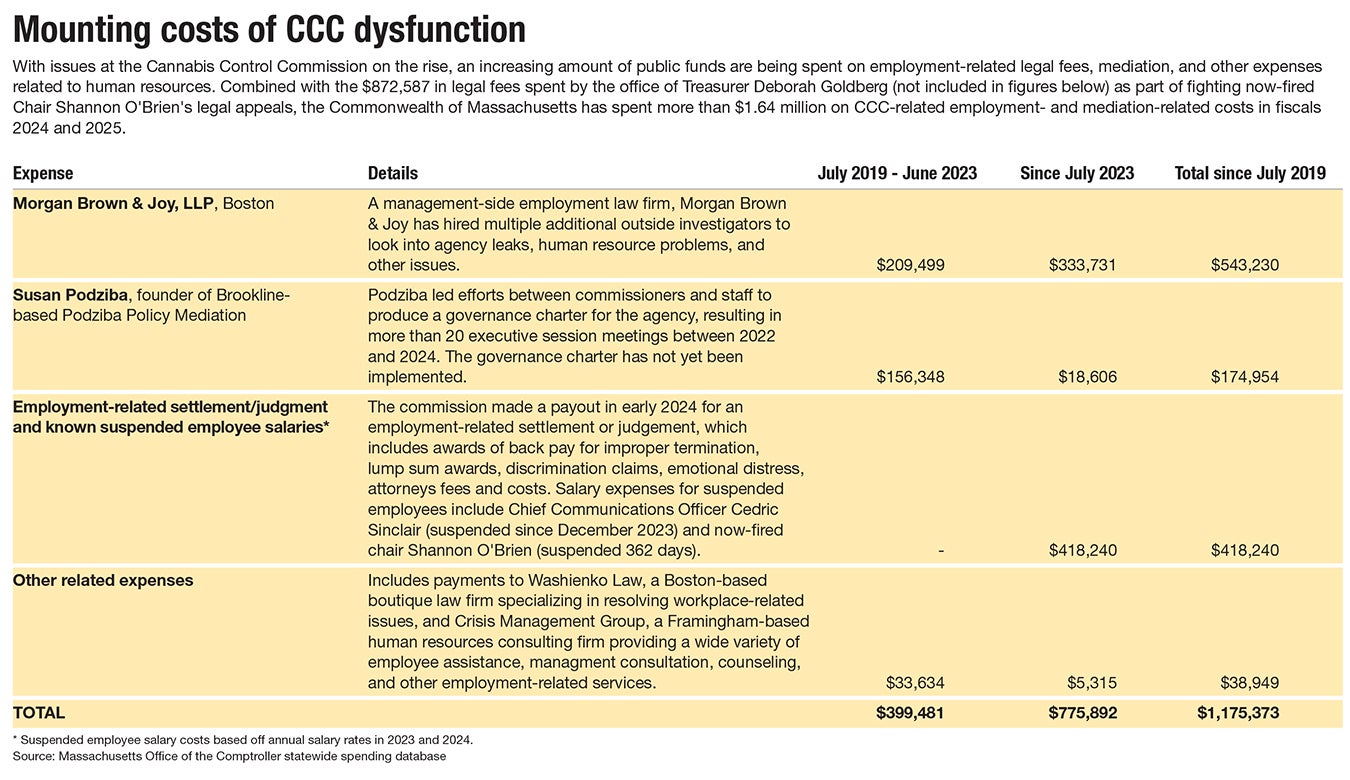

In July 2022, Podziba set December 2022 as the deadline for the mediation to conclude, according to meeting minutes. But the process ended up dragging into November 2023, costing around $175,000.

While portions of the minutes released this summer seem intentionally vague — referring, for example, to topics that were discussed without specifying who raised them — they nonetheless offer a glimpse at some of the issues dividing CCC leaders.

One focal point appears to have been the increasingly negative staff culture, something participants mentioned at least 25 times throughout the sessions, according to the minutes.

In June, then-acting chair Callender Concepcion said the charter was mostly done. A draft of the charter was released in July and discussed at length during a September commission meeting, but the three commissions present ultimately decided the document needed additional work. A timeline for its implementation has yet to be released.

The long and still-ongoing process raises questions about whether the charter, even if it is implemented, will help resolve CCC’s underlying leadership issues The draft calls on the chair and executive director to work together cooperatively without directly addressing what the next steps should be if cooperation fails to materialize.

There’s also question of if the draft reflects the viewpoints of current officials: Seven of the 11 officials who were participating in the mediation as of December 2022 are no longer at CCC or have been suspended.

CCC has spent more than $1.17 million on employment-related legal fees, mediation, and other outside expenses related to human resources, according to a WBJ analysis of state financial data. More than $775,000 of that total has been spent since July 2023, according to the Massachusetts Office of the Comptroller’s statewide spending database.

The sum includes the salaries of suspended employees and a $87,969 payment made in January the comptroller’s office classified as an employment-related settlement or judgment.

A large portion of the funds, $543,230, has gone to Morgan Brown & Joy, a Boston-based employment law firm. Morgan Brown & Joy in turn has hired additional outside firms to conduct investigations into specific matters; they include Mitnick, the investigator assigned to probe the claims against Hilton-Creek, and Stephanie Chrisikos-Arendell, a trial attorney and MCAD-trained investigator with Compliance Plus in Natick, according to documents and emails obtained by WBJ.

Slow response to business struggles, consumer protection

The ongoing accountability vacuum is just one factor sapping the confidence of marijuana business owners.

Entrepreneurs have complained for years the agency moves far too slowly and is generally unresponsive to their concerns. The problem has hindered further growth in the industry, said Ryan Dominguez, executive director of the Massachusetts Cannabis Coalition trade association.

While companies in regulated industries routinely grumble about their overseers, the delays have been especially costly in the cannabis industry because it is so young and fast-evolving, meaning changes can easily come too late to have their intended impact, Dominguez said.

“Massachusetts is a [cannabis] market that is just not one of those places that people are looking to invest in right now, and I don’t know if all of the news coverage that has come out has helped,” said Dominguez. “There’s a lot of transition that’s happening at the CCC, and that leaves the whole industry in a really tough position.”

In Worcester County, the marijuana industry has quickly become a part of the local economy. The region is home to 85 adult-use dispensaries with at least a provisional license to operate as of October, according to CCC data. That number is nearly double the 49 from 2020. More prospective cannabis businesses have applied for licenses in Worcester County than any other county in Massachusetts.

The industry remains a cash cow for government coffers, as recreational marijuana is taxed at a 20% rate. Statewide, marijuana sales and fees generated $292.4 million in state tax revenue in fiscal 2024.

Despite those figures, increasing competition, dropping prices, and undue regulation have created problems for business operators in the cannabis industry.

Multiple Central Massachusetts businesses closed their doors for good in 2024, including Harmony dispensary in West Boylston and Society Cannabis Co. dispensary in Clinton.

The wholesale price of cannabis in Massachusetts plummeted nearly 67% from more than $416 an ounce in January 2020 to an all-time low of under $138 an ounce in September, according to CCC data.

These difficulties are not limited to Massachusetts, as legal marijuana markets in other states have seen shake-outs as competition increases. But challenging business conditions add greater urgency to a laundry list of regulatory changes businesses are seeking, some of which have been pending for years, said Laury Lucien, a Boston-based cannabis attorney and entrepreneur.

“People in the industry are frustrated and disappointed, because [commission leaders] are supposed to be professional, and this is affecting their livelihoods. People have invested their entire life savings into these businesses,” Lucien said. “All the energy that went into the bickering and the back-and-forth and arguing about who will be the interim chair could have been used to create a better industry.”

The reforms sought by businesses and advocates include relaxed security protocols for marijuana deliveries, more stringent worker safety requirements, the long-delayed implementation of social consumption pot cafes, and fixes to the state’s unreliable cannabis testing system.

On the question of deliveries, the commission has made some progress, albeit at a snail’s pace.

In December, commissioners voted 4-1 to delete a requirement calling for two people to be present for every home delivery of marijuana.

Initially intended to discourage robberies of vehicles carrying cannabis, business owners even before the start of deliveries in 2021 had warned the rule was financially infeasible, logistically difficult, and did little to increase security. Ever since, they have lobbied for it to be rescinded and eventually persuaded the cannabis commission to acquiesce.

However, the vote to remove the rule has yet to be implemented. At a meeting on Oct. 25 , commissioners were expected to formally enact the change, but instead stumbled over the question of whether it applied to wholesale deliveries between marijuana companies in addition to home deliveries, disappointing operators who were already upset at the delay following the December policy vote.

In the meantime, operational delivery companies say they have struggled to stay afloat. Multiple prospective delivery companies have abandoned their license applications, part of an upward trend in licenses being surrendered, according to Boston Business Journal.

Other regulations have lagged even longer. None more so than licenses for so-called social consumption venues, cafes where patrons can legally consume pot, which were envisioned by the 2016 ballot initiative. Eight years later, rules to allow for pot cafes still not haven’t been finalized.

While part of the delay is attributable to a hitch in state law — since fixed — preventing municipalities from holding votes to approve the facilities, CCC in 2023 voted to scrap an earlier set of provisional rules and restart the process of drafting regulations. That means the venues are unlikely to open before 2026 at the very earliest, 10 years after Massachusetts legalized marijuana and long after states such as California and New Jersey approved rules for cannabis cafes.

Issues surrounding the testing of products to ensure product safety and accuracy of labeling is a concern across the industry, but has been particularly prominent in Massachusetts, where accusations of fraud and businesses shopping between labs to get more desirable testing results have been common knowledge in industry circles for years.

In October, an investigation from the Wall Street Journal found from April 2021 through 2023, labs in Massachusetts that failed fewer tests than other labs in the previous year tested a median of 84% more samples during the following 12 months, suggesting growers were seeking out labs likely to approve products with higher levels of contaminants.

Product safety issues have caught the attention of state watchdogs. In September 2023, an audit from State Auditor Diana DiZoglio found CCC had allowed more than $10 million in products with expired testing approvals to be sold to consumers.

Johnson, the CCC chief of research since 2018, told the WBJ she tried in vain for years to obtain testing data but was rebuffed. Then, at a science-themed cannabis event she attended in December, she was shocked when one speaker presented a thorough analysis of the very data she had sought, accessed via a public record request.

Once Johnson got access to the data herself, it didn’t take long to find obvious indicators of fraud.

“We analyzed it, and then we realized that there was a huge issue with the data and how labs are reporting total yeast and mold,” Johnson said.

The agency did not respond directly to Johnson’s claims.

Data from some labs showed a massive number of samples fell just below the state’s threshold for contaminants like mold, she said, while virtually none were above the threshold, a near impossibility statistically, she said.

CCC has scheduled a Nov. 7 hearing to receive feedback from stakeholders on the issue of testing fraud.

One issue CCC did move quickly on was allowing the transport of marijuana to the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, which lie across federal waters from the mainland. Because of marijuana’s illegal status at the federal level, the practice had previously been banned, leaving dispensaries on the islands with extremely limited access to products.

In June, CCC issued an administrative order permitting shipments over intrastate waterways. The order came after a lawsuit was filed in May by Vicente LLP, a Denver-headquartered cannabis law firm working on behalf of island dispensaries.

CCC moved to enter settlement negotiations within nine days of the lawsuit being filed, according to a press release from the firm. The quick regulatory change came as part of the settlement of the lawsuit, suggesting businesses who need urgent action from the agency may increasingly head to court for a solution.

CCC leaders downplay their objectively slow pace of work and attack their critics.

On Friday, acting-chair Bruce Stebbins wrote a letter to the editor in the Boston Globe in response to reporting on industry mold problems, saying the article may have caused unnecessary alarm over product safety but without addressing specific claims.

Commissioners and high-ranking officials such as Hilton-Creek have frequently made comments criticizing media coverage of the agency during public meetings, insisting the commission remains on track by pointing to new employee hires and emphasizing total sales figures.

These statements from CCC leaders frustrate business owners who know the reality of the industry, said Dominguez.

“The state revenue numbers are the ones that are used most and quoted most often, but I think it’s not telling the full picture,” said Dominguez. “If you look at how much people are actually profiting versus their tax burden and things behind the scenes, I don’t think those numbers are telling the true picture.”

A lack of accountability

If lines of authority are muddled within the commission, that’s true externally, too.

Under state law, the commission does not answer to a single political authority; its five commissioners are appointed variously by the governor, attorney general, treasurer, or jointly by all three.

That was a change from the 2016 ballot initiative that legalized recreational marijuana sales in Massachusetts. In it, voters approved a three-member agency under the treasurer’s office, which directly oversees the state Alcoholic Beverages Control Commission.

State lawmakers in December 2016 paused implementation of the legalization law, and the next summer passed a revised version centered around an independent, five-member commission, modeled after the Massachusetts Gaming Commission.

While the move was intended to insulate the agency from undue political interference, Lucien said it insulated the commission from accountability amid its current crisis, leaving it unclear who should step forward to right the ship.

“At this point, with all the chaos and all the things going wrong simultaneously, there needs to be a grownup in the room,” said Lucien. “Someone should be given the final say to jump in and set things in order and tell all these people, ‘You’re in time out.’ I’m not sure if receivership is the best option, but there has to be some form of accountability to ensure the successful operation of the commission and the industry, and that may need to come from the Legislature.”

Indeed, a review of news coverage suggests the three appointing authorities, along with top legislative leaders, have mostly been at pains to distance themselves from the commission’s woes.

House Speaker Ronald Mariano, for example, said on WCVB-TV’s “On The Record” in 2023 lawmakers who wanted additional oversight of the agency were “folks who want to get in the middle of a fight.” Commenting in October about this year’s spate of ballot initiatives, Mariano seemed to partially blame voters themselves, telling State House News Service he was “no fan of making laws by ballot initiative, after seeing how screwed up the marijuana thing got.”

Even Goldberg, who stepped in to fire O’Brien and is responsible for appointing the agency’s chair, has otherwise disavowed responsibility for fixing the ailing cannabis commission.

“I’m not being cute here. We don’t have oversight,” Goldberg told reporters in October, according to State House News Service. “We have no way of really knowing what goes on over there, so I have absolutely no idea.”

CCC leaders have cast some blame at the legislature, noting in public meetings lawmakers have refused to fully fund the agency’s most recent budget request. Callender Concepcion said in December to State House News Service elected officials were trying to create false narratives about the agency.

The road ahead

Current and former employees who spoke to WBJ largely agree on one key principle: There’s little hope for the agency to get back on track without outside intervention.

Dube suspects commissioners knew early on installing Hilton-Creek as the acting executive director was a mistake, but they are afraid to acknowledge the mistake while state legislators are considering overhauling the agency or even putting it into receivership.

While Dube sees Hilton-Creek as a major obstacle to reforming the organization, she – along with Johnson and other current and former employees – have doubts the agency’s four remaining commissioners will be able to refocus the agency on its work.

“I kept trying to give [commissioners] the benefit of the doubt, but inaction is action,” Dube said. “The pain of hearing them in public meetings talk about how great Hilton-Creek is and how she’s doing so much is so incredibly painful. It’s a slap in the face. I think they are culpable.”

Eric Casey is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the manufacturing and real estate industries. Dan Adams is a freelance reporter who covers cannabis and drug policy.