The simple narrative proclaiming the craft beer industry is dying may fit nicely into a headline or television news chyron, but it doesn’t begin to explain the complexities of the local craft beer space.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

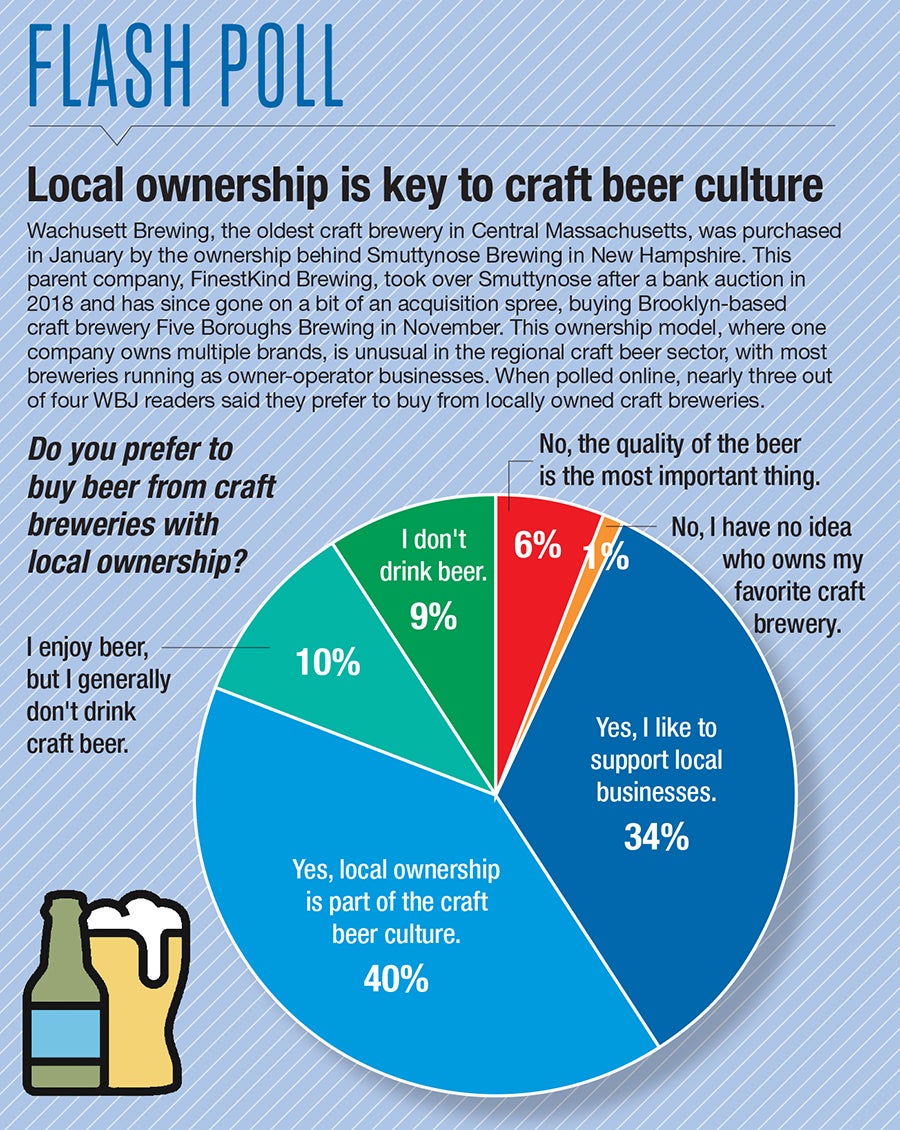

The January purchase of Wachusett Brewing in Westminster, the oldest craft brewery in Central Massachusetts, by Finestkind, the craft beer parent company behind New Hampshire’s Smuttynose Brewing, may have come as a surprise to the casual beer consumer.

But for those in the know, this acquisition was just the latest example of the changing craft beer landscape.

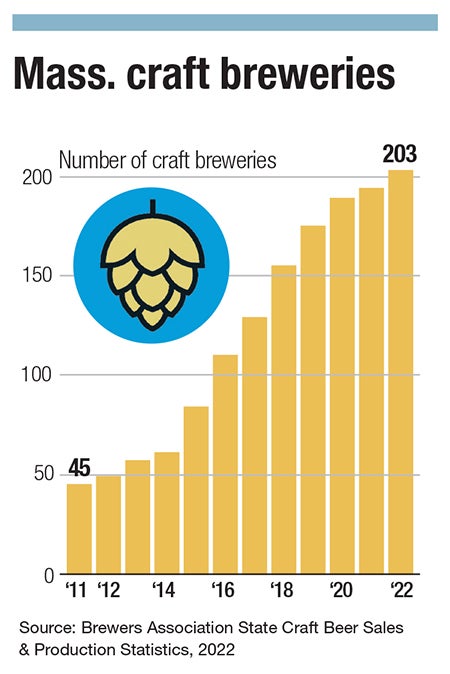

As the craft boom of decades prior fades into memory, operators in the space are finding themselves faced with a number of challenges. Discussions of mergers and acquisitions, changes in consumer preferences, and the persistence encroachment of some of the world’s largest alcohol companies are becoming more commonplace.

The simple narrative proclaiming the craft beer industry is dying may fit nicely into a headline or television news chyron, but it doesn’t begin to explain the complexities of the Central Massachusetts craft beer space.

Operators throughout the region, from companies brewing tens of thousands of barrels a year, such as Charlton-based Tree House Brewing, to the smallest of micropubs, still sell their creative products to legions of fans and customers. Others haven’t been so fortunate, as businesses like Milk Room Brewing in Rutland and River Styx Brewing in Fitchburg have closed their doors for good.

Today’s challenges are far from insurmountable, but it’s clear as the craft market matures, operators themselves will have to evolve, while remembering the collaborative spirit that helped make the industry what it is today.

Crafty conglomerates

The Brewers Association, a Colorado-based national trade group of more 5,400 beermakers, has a straightforward definition of how to qualify for its designation as an independent craft brewery: the brewery must have annual production of 6 million barrels or less, and it must be independent, meaning less than 25% of the brewery is owned or controlled by a alcohol industry member that is not itself a craft brewer.

The official certification logo provided by the association to approved craft entities may be something beer aficionados look for, but the casual consumer is more likely to pay attention to flashy packaging or amusing names of some brews. There’s little stopping a brewery from calling itself as craft even if it doesn’t make the association’s definition.

“There’s a lot of crafty brands out on the shelves that dupe folks,” said Katie Stinchon, executive director of the Massachusetts Brewers Guild, a Framingham-based organization representing 140+ breweries in the state.

Much of this duping comes from the biggest alcohol companies. Since the emergence of the craft beer scene in the 1990s, companies like Illinois-based Molson Coors and Belgium-based Anheuser-Busch InBev have been producing products under smaller brand names, utilizing packaging and marketing to appear more akin to something created in a garage by hipsters than by a multi-billion dollar conglomerate.

“There’s mega-corporations putting out craft-like products or simply purchasing craft brands,” said Rob Day, vice president of marketing at Jack’s Abby in Framingham. “It’s fair to say the average consumer outside of our little bubble has a harder time understanding the exact definition [of craft].”

Anheuser-Busch InBev, the largest brewer in the world, has purchased multiple craft breweries, including its September 2020 purchase of Craft Brew Alliance, an Oregon company that itself had purchased smaller breweries in its 11 years of existence, including Kona Brewing in Hawaii.

Even large businesses with zero prior beer experience have jumped into the fray.

In 2020, Aphria, a Canadian company solely focused on the cannabis industry, diversified its portfolio by purchasing Atlanta's SweetWater Brewing for $250 million in cash and $50 million in company stock. Aphira would later be absorbed by Tilray Brands, a multinational company based in New York previously focused on cannabis, with Tilray going on to make additional purchases of craft breweries. The company holds 5% of the U.S. craft beer market and is the fifth largest craft brewer in the country, according to a Tilray press release issued in October.

“Larger corporations buy these brands for a reason. They’re not buying just to throw money out of the window,” said Kim Golinski, president and general manager of Wormtown Brewery in Worcester. “To say ‘I can’t drink this because Anheuser-Busch made it,’ that’s a pretty small mindset to have.”

Corporate players have yet to convince any Mass. breweries to cash out, but mergers and acquisitions between small to midsize players like Wachusett and Smuttynose are more common; RiverWalk Brewing in Newburyport and Ipswich Ale Brewery announced a merger in November, with Dorchester Brewing and Aeronaut Brewing in Somerville following suit in December.

“We are seeing a little bit of a trend of people looking to pool resources and have more buying power by joining forces,” said Stinchon.

Courthouse session

At the opposite end of the spectrum from beer behemoths like Anheuser-Busch sits places like Courthouse Brew, Worcester’s newest craft beer spot.

Co-founded by Mark Gawlak and Danny Whalen, two practicing attorneys who are Central Massachusetts natives, the business brews its beers in a taproom in a brick building located in the former Whittall Mills complex, adjacent to Mrs. Moriconi's Ice Cream shop and a number of other small businesses.

In addition to being available at its modest-yet-trendy taproom, Courthouse’s brews are on the beer list of a handful of local restaurants. Gawlak and Whalen started brainstorming an entry into the space while enjoying the wide selection of drafts at Brew City, a bar and grill on Worcester’s Shrewsbury Street.

“Being able to sample a lot of different beers, you get a general understanding of the flavor profiles of every sort of beer and then ask what we could do differently,” said Whalen.

Even with their legal backgrounds, the maze of regulations at the federal, state, and local levels was a lot to handle.

“You have to have your lease signed and some other stuff squared away to start your federal paperwork,” said Gawlak. “Until you get your federal paperwork, you can’t start the process at the state level. Until you get your state permit, you can’t start the process at the local level. It really hamstrings potential small business owners from starting.”

The brewery opened more than a year later than Whalen and Gawlak’s initial plan. Now, Courthouse has attempted to be a bit of a trendsetter, producing less common brews.

The more common variations of India pale ales are still present, but the business makes Strict Scrutiny, an Irish red ale, and Attractive Nuisance, a fruited IPA with notes of cinnamon sugar and milk, which was the first beer Gawlak and Whalen produced, inspired by a dish at Worcester’s Pampas Churrascaria, a Brazilian steakhouse.

The brewery’s selection is the latest confirmation the days of craft breweries sticking to three or four beer types are a thing of the past, one of the many ways operators have had to adapt to changing consumer preferences and trends.

Changing preferences

Customers looking to branch out from IPAs have more choices than ever, ranging from alcohol-infused sodas and seltzers, to cannabis-based beverages, to non-alcoholic beers and mocktails.

Beyond changes in preferences, the industry is dealing with more worrying trends. Bustling taprooms play a key role in the business plans of breweries, particularly smaller ones, but breweries are among the entertainment venues reporting smaller crowds since the COVID-19 pandemic, said Day from Jack’s Abby.

“On-premise keg volume has not recovered to 2019 and prior numbers, even though a lot of indicators might have shown that it should have,” he said.

Perhaps most alarmingly for brewers of all types, the generation reaching adulthood near or during the pandemic doesn’t seem nearly as interested in alcohol. A 2020 study published in JAMA Pediatrics, a monthly peer-reviewed medical journal published by the American Medical Association, found 28% of college students in 2018 reported they abstained from alcohol, up from 20% in 2002.

“Anyone who turned 21 just before, during, or right after COVID is just not coming out,” Golinski said. “They are still drinking beer, but it’s a lot less and a lot less socially.”

Craft comradery

While it’s clear the producers are facing some headwinds, the craft industry does have a wildcard: a friendly and helpful spirit between competitors.

“It’s like big brother or big sister helping out little brother or little sister,” Golinski said. “The industry is about relationships, and there’s all sorts of friends in the industry. I know that Wormtown has been a big proponent for helping the small guy out.”

The sharing of ideas and resources between companies outsiders might assume are arch-rivals is commonplace, especially with companies new to the space.

“Everybody is extremely welcoming, willing to help out if you have any questions,” said Whalen. “No one is trying to gain an advantage in any way. They are more apt to hand you a four pack and say ‘Here, try this,’ which makes it a great scene to be a part of.”