It’s been more than two years since COVID-19 first wreaked havoc across the globe. Despite this, the pandemic rages on across Central Massachusetts for a third summer.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

It’s been more than two years since COVID-19 first wreaked havoc across the globe. Despite this, the pandemic rages on across Central Massachusetts for a third summer.

The minor annoyances and changes to our routines all seem commonplace. At-home tests, masks, and social distancing have dominated our lives for better or worse the last few years. But this time around the state seems more prepared than ever to deal with the omnipresent virus.

According to the Mass. Department of Public Health, just over 90% of the population in the state has received at least one dose of the coronavirus vaccines. The state stands at one of the highest in the entire nation in vaccination rates. To date, more than 5 million residents are fully vaccinated across the Bay State. These numbers peaked in 2021 but have tapered off this year.

So what can we expect for the rest of the year as we head into the summer months?

“This is a cyclical virus,” said Dr. Richard Ellison, hospital epidemiologist and professor of medicine at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester. “Assuming no big surprises, we can expect the cases to drop and hopefully stay low until sometime around the October timeframe.”

Dropping infections

COVID-19 infections are often asymptomatic or associated with mild-to-moderate upper respiratory tract illness, which makes it more difficult to get an accurate count on the number of infections. But according to the DPH, the illness generally dissipates when the temperature rises.

“Coronavirus like all respiratory illnesses have a seasonality to them. They almost always taper off during the summer,” said Ellison. “Most viruses are killed by sunlight, and with more people congregating outside, it’s partly why we see a drop. Humidity and wind both also play roles as virus particles can’t spread through the air as quickly or dissipate more quickly.”

Ellison predicts with the drop in case numbers, the state should also see a drop in direct hospitalizations.

“At least half of the people coming into the hospital are experiencing what we call incidental disease,” said Ellison. “People are coming into the hospital because they broke their leg and then when we test them they are positive for COVID. It’s impactful for the hospital because they can’t be treated in a regular double patient room but have to be quarantined, and special precautions have to be taken.”

In mid-January of this year, according to DPH, the seven-day average for hospitalizations was 3,139 and 448 in intensive care units across the state. Roughly 14% of those hospitalized were in ICU’s. By June, the seven-day average had fallen to 597 hospitalized and 49 in intensive care units, accounting for just 9% overall in ICU’s.

“One thing is clear … People are less sick. That’s the good news,” said Ellison. “We are still seeing a lot of people coming into the hospital for COVID-19 who are already vaccinated, but their symptoms are much milder. Overall, we’re seeing a lot less intubations and long-term hospital stays than when the virus first hit our state.”

Vaccine disparities

Vaccines will continue to play a large role in keeping the virus at bay. However, according to Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, only 54% of Massachusetts children ages 5 to 11 have had one shot in their arm. In addition, many communities have rates exceeding 90% while there remain many communities whose vaccination rates are below 50%.

“We should set a goal of at least 70%, which is still well below the rates of first dose shots for children ages 12-19,” said Alan Geller, senior lecturer, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Harvard Chan. “As can be seen in the vaccination rates by community, we can see huge disparities. It is for the youngest age group, children ages 5 to 11, where we have seen the starkest disparities by where one resides.”

As of March of this year, Worcester stands at 41% for schoolchildren ages 5 to 11 years old having received at least one dose of vaccine. In neighboring Shrewsbury, that number stands at 72% of schoolchildren ages 5 to 11 years old having received at least one dose of vaccine. The numbers become even more stark in the suburbs around Boston. In the city proper, the number stands at 48% while surrounding towns like Newtown stand at 95% of 5 to 11 year old’s receiving at least one dose of vaccine.

Social determinants of health

Some of the biggest barriers impacting vaccine equity are called health determinants. These determinants can impact patient health and are stressed as important indicators of overall population health. These indicators include social norms and attitudes, exposure to crime, socioeconomic conditions including poverty and access to reliable transportation.

“Vaccination equity is huge,” said Dr. David Brumley, chief medical officer of Worcester insurer Fallon Health. “It’s more important for vulnerable populations to get vaccinated because they generally have underlying health conditions which could exacerbate symptoms.”

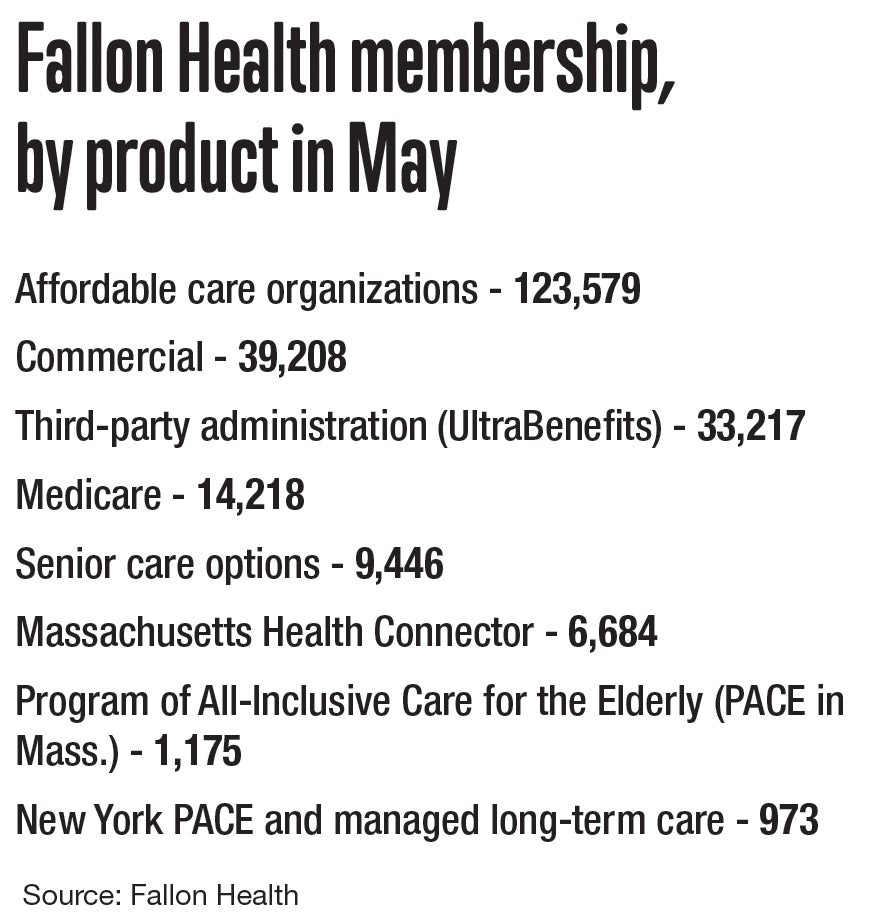

One of the programs Fallon Health spearheads is the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. Most of the participants who are in PACE are dually eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. The program provides comprehensive medical and social services to elderly folks living in the community.

“We cover transportation for our PACE members, and we do outreach as well,” said Brumley. “Early on in the pandemic, we made it a point to call each and every one of our members to see how they’re doing or if they needed transportation to get tested. Once vaccines became eligible, we immediately reached out to all of our members to see if they needed a ride.”

Members that qualify for dual eligibility in the PACE program receive both a nurse and a navigator. The navigators make sure members can get to appointments, get vaccinations, or coordinate services they need.

“With our Medicaid population, we did a texting education campaign and ended up being in the top five for vaccination rates for all 17 provider partnerships in the state,” said Brumley. “We also had mobile health units where we had clinical staff to drive around to people’s homes if they needed at-home services. We wanted to make sure we could come to them if they couldn’t come to us.”

Fallon Health is piloting a program called Hospital at Home where patients who need acute treatment in a hospital but are stable enough to stay at home can do so. The program, which launched in January, sends medical equipment to patients homes where nurses conduct visits throughout the day.

“It’s important to sometimes help keep vulnerable populations at home,” said Brumley. “This program allows people who may be more susceptible to catching COVID-19 in a hospital the option of staying in their homes where they are less likely to catch the virus.”

While vaccine equity will be a problem effecting overall population health, vaccines will be administered for the foreseeable future. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention announced earlier this year COVID-19 is here to stay and that we are beginning to transition from a pandemic to an endemic, or a virus that is constantly present but manageable.

“We will continue to see ebbs and flows in COVID-19 numbers,” said Ellison. “We also can expect to see more variants down the line much like the flu every year. It’s important that people continue to get booster shots especially among the most vulnerable populations. The best hope is that severity in sickness continues to decrease as more people get their boosters and more people build immunity.”