Biopharmaceutical jobs are more clustered in MetroWest than practically another other industry except for information technology, and they’re high-paying and growing fast.

A group advocating on life science companies’ behalf wants to help make sure communities are ready to accommodate the growth of existing companies or others that may want to move in.

The Massachusetts Biotechnology Council, a nonprofit formed three decades ago to support the state’s life sciences industry, is aiming to make it easier for communities to make themselves ready through the right zoning and permitting programs.

“We’re only going to show them to the communities that are most willing to accept them,” said Robert Coughlin, MassBio’s president and CEO.

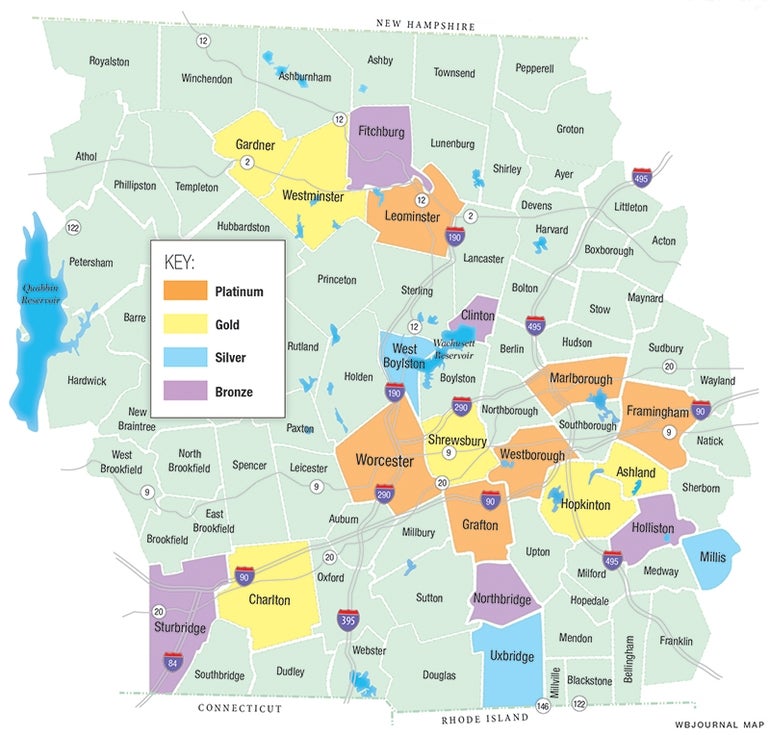

Cambridge nonprofit MassBio has created a scoring system called BioReady for communities to both give cities and towns something to strive for and make it easier for biotechnology companies to know where they may have the clearest path toward putting a shovel in the ground for a new project.

“The top issue is speed to market,” said Tony Coskren, the executive managing director at Newmark Knight Frank, a Boston company helping life science and other companies find space in the area, including along I-495. “For companies, it’s ‘How do I become operational as fast as possible?’”

Massachusetts is a national leader when it comes to life sciences. It has the most biotechnology research and development jobs in the country, and its number of biopharmaceutical jobs has grown by 28 percent in the last decade to reach 66,000, according to MassBio.

Central Massachusetts alone has more than 50 life science companies, including Abbvie in Worcester, Bristol Myers-Squibb in Devens, Sanofi Genzyme in Westborough and Framingham, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals in Marlborough.

But MassBio and others aren’t resting.

“We created BioReady because we needed cities and towns to choose to compete,” Coughlin said at a regional life sciences forum in Marlborough in February. “I’ve gotten mayors calling me up disappointed that they don’t have better ratings, but we want them to be ready for these companies that we represent.”

PlatinumReady

Grafton is among those with the top rating – platinum – despite being smaller and less developed than its fellow communities at the top rung, like Framingham, Marlborough and Worcester. MassBio says platinum communities have zoning allowing for biotech laboratory and manufacturing uses by special permit, and public water and sewer infrastructure in all commercial and industrial areas.

Grafton has acres of unrealized development potential and is ready for it.

The 80-acre Grafton Science Park, owned by a subsidiary of Tufts University and adjacent to the Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, has a capacity for 440,000 square feet of life science office space in a cluster of planned buildings to join the Tufts New England Regional Biosafety Laboratory, a research facility.

The town has rezoned 40 acres for similar use on the same side of Route 30. Town officials are helping to craft state legislation to open a nine-acre parcel of the former Grafton State Hospital off Centech Boulevard for mixed use to help draw development.

“The platinum is what gets people in, but we want to show them Grafton is forward-thinking,” said Joe Laydon, the Grafton town planner.

Grafton’s Town Meeting last fall approved engineering for what would be a 1,500-foot sewer line expansion from the west along Route 30 to the area to provide more capacity for businesses. The town has made the area attractive to companies wanting to be next to higher education research facilities and down the street from a commuter rail stop.

“When we said we could act as a magnet for life science company activities, they were enthusiastic and active partners,” Joseph McManus, the executive associate dean of the veterinary school, said of the town.

Achieving gold

Ashland – which was just upgraded last month from bronze to gold – is sandwiched between Framingham and gold recipient Hopkinton, two communities with far more developed life science industries. The town is looking to catch up.

“We really want to have more of a biotech community here because we feel like we offer a lot of the things [those companies] are looking for,” Ashland Town Manager Michael Herbert said.

Ashland’s success story for life sciences is the Ashland Technology Centre, the former Telechron clock factory housing tenants like MatTek, which engineers human tissue, and BioSurfaces, a maker of medical device technology.

Lower rents and a strong school system have helped draw such companies to Ashland so far, Herbert said.

“That’s something that businesses that have moved in – not just life sciences but others – have remarked about, the affordability,” he said.

BioSurfaces moved to the Ashland Technology Centre in 2010, more than tripling its space. BioSurfaces co-founder Matthew Phaneuf, an Ashland resident, called the town a hidden gem.

“There are oher biotech companies here that a lot of people don’t know about, but they’re fairly successful,” he said.

Holliston has a bronze rating, hurt in part by a lack of a town-wide sewer system or commercial- or industrial-zoned areas. The town lost a potential business because Holliston doesn’t have direct highway access, said Jeff Ritter, the Holliston town administrator.

On the other hand, Holliston created an economic development committee three years ago to explore potential opportunities, and has a capacity for up to 2 million square feet of space in the Hopping Brook Park development off Route 16 near the Milford line.

“We’re really committed to economic development. We’re open for business,” Ritter said. “But there are some challenges.”

The MetroWest cluster

Life sciences are critical to MetroWest in particular, thanks in large part to Framingham, Marlborough and Natick, which each have a dozen or more life science companies and host heavyweights like Boston Scientific, Sunovion and Sonofi Genzyme.

The Public Policy Center at UMass Dartmouth studied the MetroWest workforce and found biopharmaceutical jobs were the second most-clustered jobs in the region compared to the national average, behind only information technology and analytics, an industry that has actually been shrinking in job numbers since 2010.

Life science jobs have grown quickly in MetroWest. Biopharmaceutical jobs grew by 18 percent from 2010 to 2016, hitting nearly 4,000 in total, the UMass Dartmouth report found.

“Our region has a tremendous life sciences and medical device cluster,” said Paul Matthews, the executive director of the 495/MetroWest Partnership.

“We’ve seen a marked change where more and more life science companies are recognizing the potential value of locating in this region because we have a highly skilled workforce and transportation, and a price advantage compared to Boston,” Matthews said.

Communities have reasons to want to bring in life science jobs.

Jobs in the industry are high-paying: the average scientific research and development worker in MetroWest makes $167,000, according to a regional study released in January by the Public Policy Center. Someone in pharmaceutical manufacturing makes an average of $165,000.

More growth is ahead. Biologics company LakePharma bought a 69,000-square-foot facility in Hopkinton in February, and medical device maker Insulet broke ground last fall on a $100-million, 350,000-square-foot facility in Acton.