The coronavirus pandemic and the economic pain it is causing has brought a flood of new deposits to banks in Central Massachusetts and nationally.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The coronavirus pandemic and the economic pain it is causing has brought a flood of new deposits to banks in Central Massachusetts and nationally.

The trend hasn't been entirely good.

“Everyone can see the storm clouds on the horizon, and we just keep waiting for them to come,” said Todd Tallman, president of Cornerstone Bank in Southbridge.

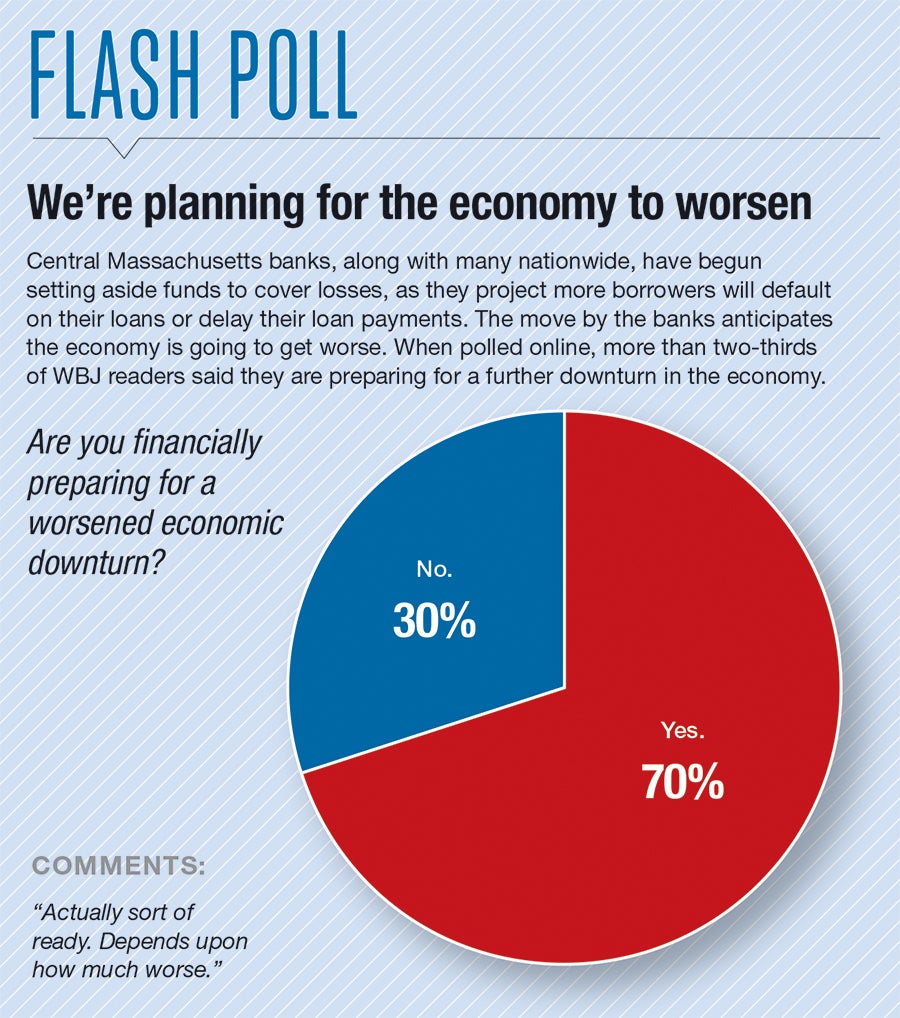

Banks have seen net incomes drop precipitously and are setting aside far greater amounts of expected potential losses in loans and leases, according to a Worcester Business Journal review of Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data.

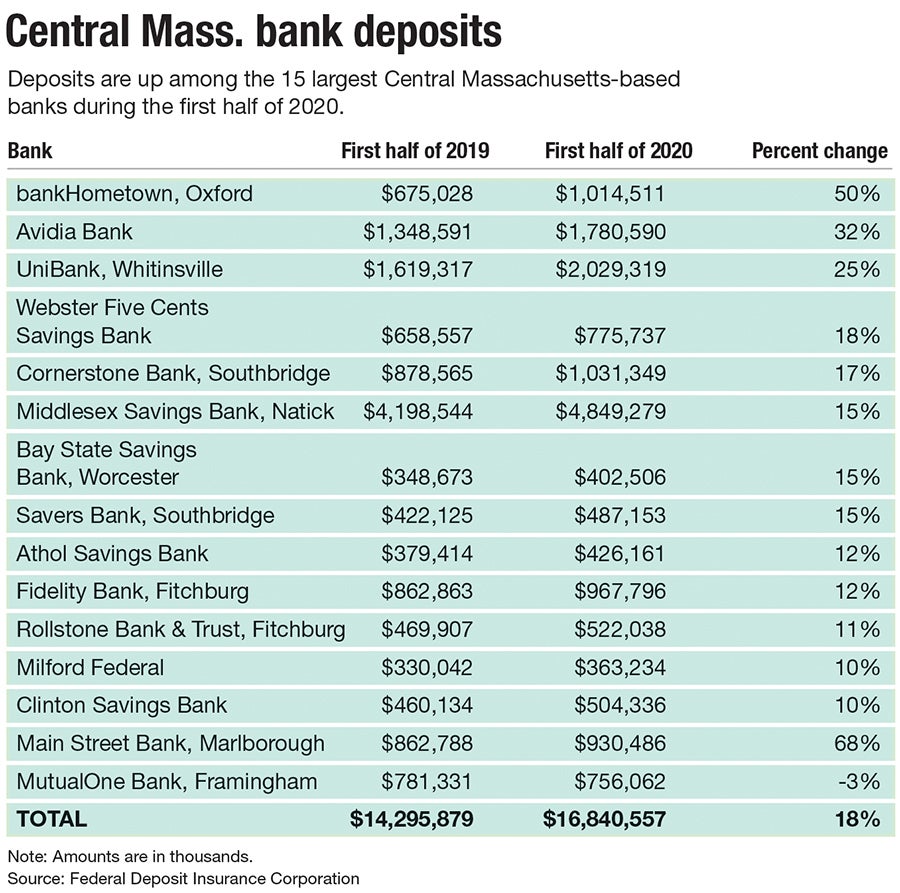

Across the 15 largest locally-based banks by deposits, the first half of 2020 saw deposits soar by 18%, or more than $2.5 billion, compared to a year earlier.

“Banks on the whole are flush with deposits,” said Brian McEvoy, a senior vice president at Webster Five Cents Savings Bank, who leads its retail banking division. “Growth year-to-year is really historic.”

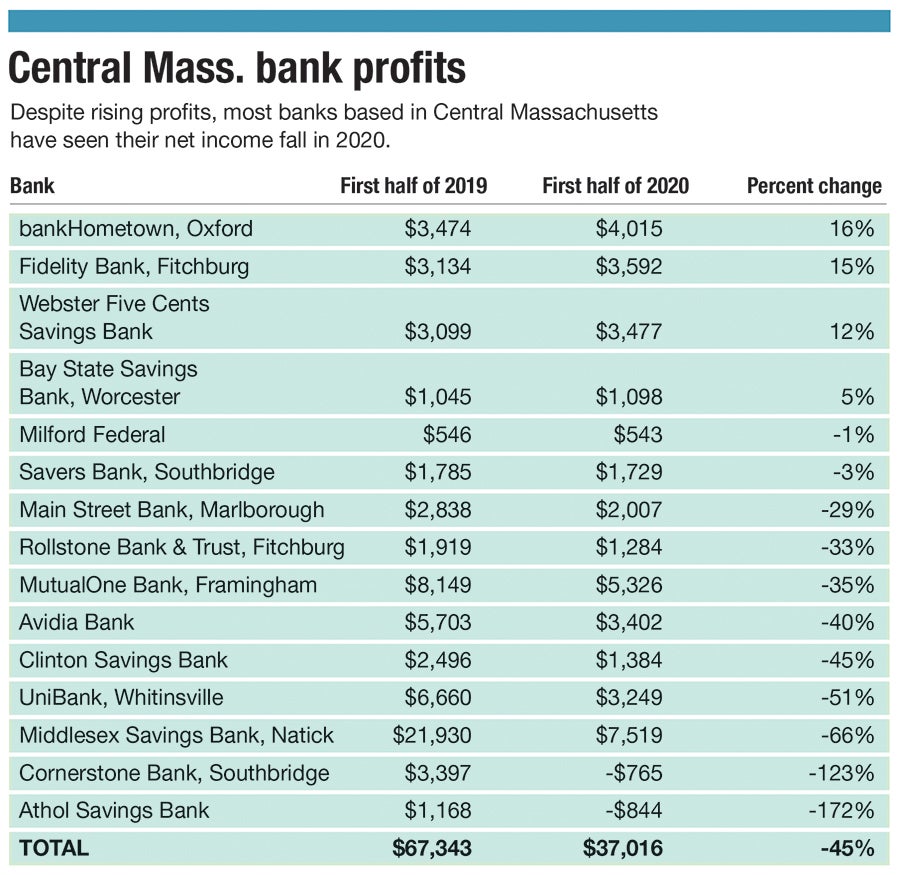

Bank profits, though, dropped by 45%, or more than $30 million, due in part by exceptionally low interest rates.

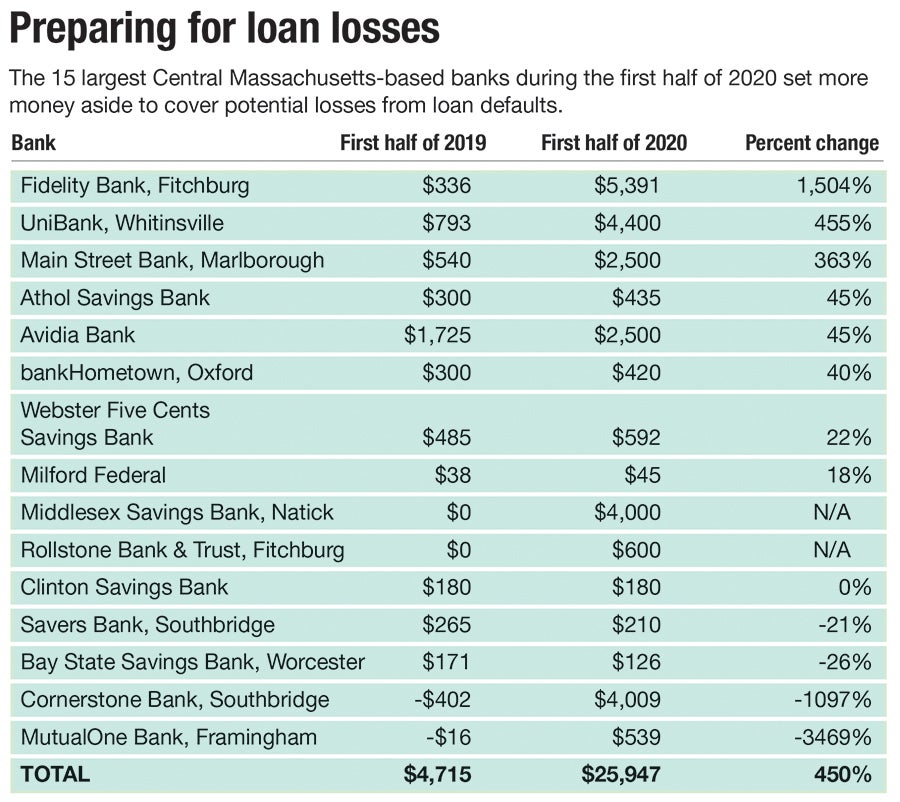

And in a sign banks may be expecting credit repayment issues, the amount of money they're setting aside for those losses is more than four times the amount they set aside for such losses in the first half of 2019. Those banks set aside nearly $26 million for what are called credit-loss provisions in the first six months of 2020. Among them, Middlesex Savings Bank, the largest Central Massachusetts-based bank by deposits, put $4 million aside for those losses this year. Last year, it didn't report having any money in that account.

Nationally, the FDIC has seen the same trends.

For the second straight quarter, new deposits exceeded $1 trillion, something FDIC Chairwoman Jelena McWilliams said surpassed anything seen nationally by banks before. Deposits grew 21% from a year prior.

“These inflows demonstrate public confidence in the banking system, as well as the system’s ability to accommodate unprecedented customer demand,” McWilliams said.

Soaring deposits

Bank industry leaders locally said spiking deposit numbers are attributable to a few causes.

Most people have kept their jobs but have fewer places to spend without traveling or going out to eat as much. Many are putting more money aside in secure bank accounts to ride out a less predictable time for the stock market.

“When there’s uncertainty in economic times, people tend to be more conservative with their investments,” said Jon Skarin, the executive vice president of the Massachusetts Bankers Association.

Americans are saving far more money than they have in decades.

The national personal savings rate spiked to 34% in April and remained at nearly 18% in July, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Since such records began in the 1950s, the rate has never before exceeded 17%, and that was in 1975.

Federal aid is playing a factor.

The $669-billion federal Paycheck Protection Program gave small businesses a financial lifeline during the pandemic, including 346 loans of $1 million or more in Central Massachusetts. Much of those loans don’t need to be repaid if they keep people employed.

Nearly all Americans received $1,200 stimulus checks. In the cases of both businesses and individuals, enough of those federal funds are sitting in bank accounts to make a substantial difference, bank officials said.

At Webster Five, more than 60% of deposit growth came from business customers compared to individuals, a reversal from what the bank typically sees, McEvoy said.

Dropping profitability

Banks' net incomes in the first six months of the year dropped 45% in Central Massachusetts. Nationally, banks’ net incomes fell by 70%.

Each of the 15 largest Central Massachusetts-based banks were profitable in the first half of the year, but four saw net income fall by more than half.

Two factors led most directly to that drop: rock-bottom interest rates and banks choosing to put far more money aside for expected losses. Banks are generally seeing less fee revenue because of a drop in spending and borrowing.

The federal interest rate was 0.1% in August, down from a range around 2.4% last year, and a fraction of rates in the upper teens in the early 1980s.

Interest rates are the biggest driver of profitability loss, Skarin said, and something banks expect to continue for the foreseeable future.

Smaller banks are faring better than their regional or national counterparts, however, McEvoy said.

“We’re looking at very different conversations here,” he said, with such smaller banks having a different lending portfolio and having mutual ownership that buffers them from quarterly earnings shock.

At Hudson-based Avidia Bank, net income is down 40%, but Mark O’Connell, the bank’s president and CEO, said two diverging trends have somewhat offset one another: lower interest rates brought in less revenue but strong demand for refinancing home loans is up. The bank is also saving money, O’Connell said, by not having travel and other expenses it would normally incur if not for the pandemic.

Expecting tougher times

In the first half of the year, the largest Central Massachusetts-based banks set aside more than five times as much money on potential loan losses than they did a year prior. Nationally, it was nearly fourfold, from $12.8 billion to $49.1 billion.

Even that local figure may not account for how much banks are setting aside. Cornerstone Bank, for example, had less money set aside for losses through the first half of 2020 than it did a year ago, but Tallman, the bank’s president, said more has been put aside since.

Tallman, who will take over as Cornerstone’s CEO at the end of the year, said the bank is projected to set aside about $5 million for loss provisions this year, five times more than last year.

Challenging banks during this time is the unprecedented nature of the downturn. That it’s largely related to the pandemic means lessons from, say, the Great Recession, don’t necessarily apply.

Poor underwriting drove much of the 2008 recession, Skarin said, but today, loans would generally be just fine if not for the pandemic.

Banks today are taking data available to them and making their best estimates for what their portfolios are going to look like, he said.

“Obviously, there’s no pandemic data out there,” Skarin said. “I don’t think there’s any data from 1918 that a bank can run their data against what happened then.”