Inequalities in the industry persist, and large multistate operators continue to dominate the cannabis market, even in the face of several Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission programs designed to give certain groups of people a leg up in entering the industry.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

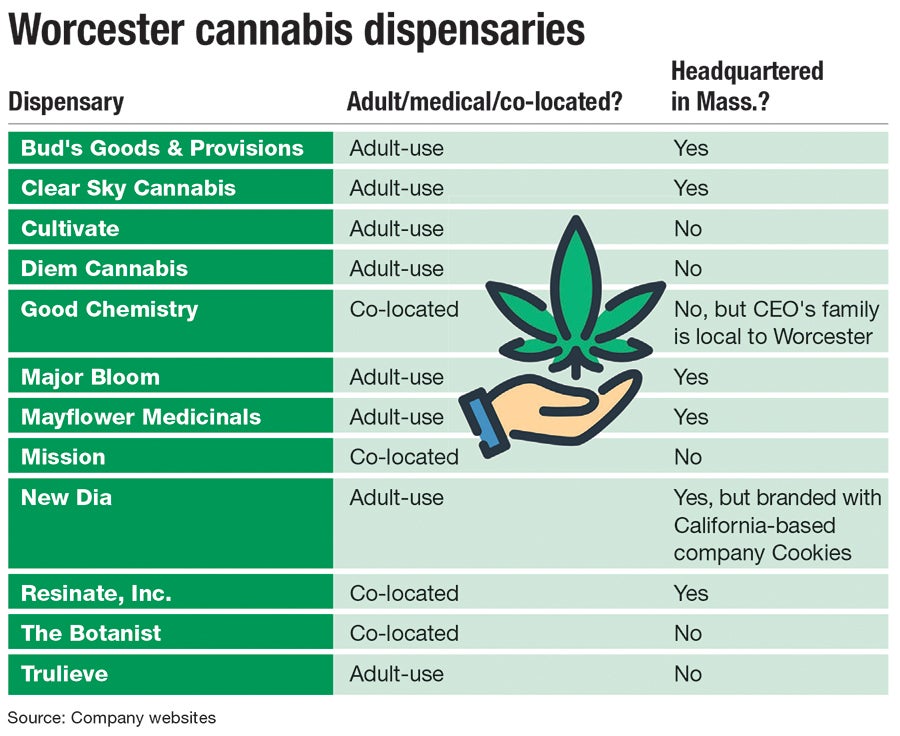

Last June, Worcester had five operating cannabis dispensaries, including both adult-use and medical options. A little over a year later, that number has more than doubled, with 12 cannabis retail shops now open for business in the city proper.

“Every time I look at our news clips, it’s about another retailer opening in Worcester, and it’s great to see,” said Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commissioner Bruce Stebbins.

That growth has taken place alongside criticism from cannabis and equity activists who say the state’s industry continues to push out those the state’s legalization program is expressly mandated to support: those from communities disproportionately impacted by the War on Drugs.

Inequalities in the industry persist, and large multistate operators continue to dominate the cannabis market, even in the face of several Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission programs designed to give certain groups of people a leg up in entering the industry, including those who are Black, African American, Hispanic, or Latino, children or spouses of someone with a drug offense on their record, or someone who has a drug offense on their own record, among other criteria.

Aside from programs intended to help minorities and other groups enter the cannabis market across a variety of entry points, ranging from ownership to employee and vendor, the CCC requires each cannabis company to set diversity hiring goals during its licensing application process, which the companies then provide updates on during the license renewal process. These components of the application are called diversity plans, and the guidance for these plans was updated and expanded in August, in part because companies struggled with writing them.

In tandem with concerns about equitable participation, the legal cannabis market has hardly stayed oriented around small and local businesses, with multistate operators comprising more than half of the current open dispensaries in the city of Worcester. One more dispensary, Cookies (formerly known as New Dia) is newly operating in partnership with an eponymous national company, based in California, creating a hybrid situation.

Although these challenges receive regular media attention – locally and beyond – equity in the state’s legal cannabis program remains a far-off goal, as CCC regulators tackle a backlog of applications and structural economic inequities push smaller, local, and minority-owned players out of the market.

Boilerplate diversity plans

In examining diversity in the cannabis market, ownership statistics only tell part of the story. As integral to following the CCC’s legal mandate to institute regulations to help people impacted by the War on Drugs is each company’s required diversity hiring plan, which is submitted with licensing applications and reviewed by the commission. This piece of the application process is intended to further attract people from diverse backgrounds into the state’s legal industry.

In the CCC’s August meeting, regulators approved expanded guidance for what should be included in these plans, which generally set internal hiring goals for minorities, women, veterans, people with disabilities, and members of the LGBTQ+ community. They prohibited applicants from using boilerplate language lifted either from the CCC or other licensing applications, after two applicants were accused of using the same wording. The effort was led by Commissioners Nurys Camargo and the aforementioned Commissioner Stebbins, who were appointed to the CCC in December.

The effort to update the guidance began after Camargo and Stebbins made their way through the first round of licensing applications that came across their desks earlier this year. In reviewing the applications, Stebbins said, they noticed many were previously reopened for revision because of their diversity plans.

With that in mind, the pair, in conjunction with a handful of CCC staff members, wanted to strengthen the guidance to help applicants understand what is expected of them with regard to writing their diversity plans, including an online resource page aimed at helping applicants put together diversity plans likely to meet their goals, Stebbins said.

“We’re not trying to set any applicant up for failure,” Stebbins said.

That companies have historically had issues with their diversity plans is not a secret. Proposed plans have long come in wide ranges, and those submitted as part of the cannabis business license application process have from time to time received criticism from commissioners for their paltry commitments to hiring employees from a wide range of backgrounds.

“It’s valuing what’s important to you,” said Laury Lucien, co-founder and CEO of the Major Bloom cannabis dispensary in Worcester. “If I never understood the importance of diversity … you can’t communicate that to me. But to them, it’s just something you kind of have to meet.”

At Major Bloom, the city’s second economic empowerment applicant to open up shop, diversity within was a priority baked into the business model. For companies who don’t inherently value diversity in their companies, Lucien said diversity plans were another box to check, like negotiating a host community agreement or finding real estate.

“That’s how it feels to them, instead of being something that’s rooted into service and what they have to do to make the world a better place,” she said.

Major Bloom, which Lucien co-founded with President Ulysses Youngblood, set high diversity standards for itself in its licensing application, including a goal to hire and work with vendors who were at least 60% minorities, women, veterans, people with disabilities, and people who identify as LGBTQ+.

The company assessed its progress toward these goals in April as part of its licensing renewal process, Youngblood said. Because Major Bloom had not yet opened, it could only report on prospective employees Lucien and he had interviewed. In their company report, the pair found 65% of job candidates interviewed were women, and 85% of candidates were people of color. They similarly exceeded their vendor goals, as well.

“Usually, it comes very natural for us, because obviously, it starts with ownership,” Youngblood said of their diversity plan and its success. “So when you have two Black owners, you know what I mean? … Believe me, I worked in corporate America for a number of years, the biggest issue when it came to diversity and inclusion was it didn’t start in leadership.”

Self-imposed limits

The City of Worcester is capped at 15 adult-use cannabis dispensaries, meaning three more will be allowed to open up shop, unless the cap is raised.

This cap comes from a state requirement limiting the number of cannabis retailers to no less than 20% of Worcester’s allotted 74 alcohol licenses, which prospective dispensary owners may pursue by entering into a host community agreement, a local required step before applicants move through the licensing process at the state level, according to an informational page on the City of Worcester’s website.

City government spokesman Walter Bird confirmed all 15 available adult-use retail licenses in Worcester are spoken for, although not all dispensaries are yet open.

“We will wait until they all open and see what the market is, and whether [they can] compete and be successful, before we entertain any thoughts of expansion,” Bird said.

As one of the first hurdles prospective cannabis businesses must pass in order to pursue licensing, host community agreements have faced increased scrutiny, as towns and municipalities are essentially left able to decide what companies they want setting up shop within their borders. They are not required to prioritize any type of applicant, although several communities have set their own standards, such as Somerville and Cambridge, which have imposed four and two-year exclusivity periods, respectively, during which they will only award licenses for equity applicants and/or, in Somerville’s case, locally-owned or co-op cannabis businesses. An adult-use dispensary has yet to open in either city.

Worcester has no such requirement.

Across all 12 dispensaries in the City of Worcester, only two are owned and operated by state-certified economic empowerment applicants – New Dia/Cookies, which opened in March, and Major Bloom, which opened in August.

Worcester is not unique in these trends, though. To date, the CCC has awarded 171 final licenses to cannabis retailers, with five of those licenses going to economic empowerment applicants, according to commission data.

The stats don’t improve significantly when looking at the CCC’s other key equity initiative – the social equity program, which provides training for entering the legal cannabis market at a variety levels, including, like the economic empowerment status, expedited license review. Out of the 986 licensing applications approved by the CCC to date, 126 are SEP participants, with 11 receiving final licenses as of the commission’s August meeting, according to the CCC.