To cover for COVID-related staff shortages, hospitals are over-reliant on travel nurses, who are paid significantly more than staff.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Workforce shortages have fueled conversations across sectors since the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, and in no industry is that more true than health care. Nursing, in particular, was hit hard: demand for nursing services became dire on day one of the pandemic, and that demand has yet to loosen its grip. To respond to an urgent need for more nursing staff, hospital systems turned to visiting or travel nurses to alleviate the temporary crisis.

But the crisis, it turned out, would not be temporary. Now more than three years since the pandemic began, contract employment of travel and visiting nurses itself is a threat to the healthcare system.

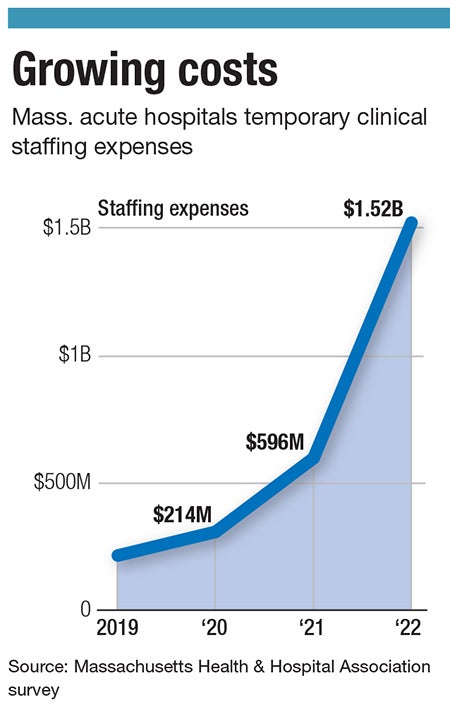

In 2022, hospitals spent $1.3 billion more for temporary staffing than they did in 2019, according to a Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association survey of hospitals representing nearly 90% of staffed inpatient beds in Massachusetts. More than three-quarters of the temporary staffing spend was on nurses, according to the study.

“This is an absolutely unsustainable model, and it's going to bankrupt our system,” Steve Walsh, CEO of MHA, said during a Massachusetts Health Policy Commission panel on March 29. Travel nurses earn higher wages compared hour to hour with staff nurses, according to the MHA.

The Central Massachusetts healthcare industry faced a shortage of workers even before the pandemic began, as the Massachusetts Department of Labor in 2018 projected six of the 10 fastest-growing professions over the next two years would be in health care. COVID exacerbated those problems, as healthcare workers faced burnout in the difficult conditions created by the pandemic.

Unchecked, unregulated component of health care

Travel nurses can earn up to three times the pay of a staff nurse, said Katie Murphy, president of the Massachusetts Nurses Association labor union, and sign-on bonuses contribute to the massive spend.

“It's a problem on so many different levels. The money is so big. We all know nurses who stepped away from their regular job to take on a contract position,” she said.

Travel nurses aren’t new. Previously, they were most commonly employed to fill temporary vacancies for leaves of absence, maternity leaves, and during periods of expansion for hospital systems, said Justin Precourt, chief nursing officer at UMass Memorial Health in Worcester. When travel nurses were being utilized as normal, Precourt said, staff at hospitals found them helpful to meet day-to-day operational and patient care needs.

“The industry isn’t new, but it was an unchecked, unregulated component of health care that got out of control,” said Precourt.

Utilization of travel nurses at UMass Memorial is down from the pandemic peak, during which they were contracted for work at three or four times the rates of 2019 and earlier, said Precourt. Still, the hospital system is still employing travel nurses about 60% more than it used to.

The situation is causing a tremendous financial strain on a system, said Precourt, and UMass Memorial is aiming for a return to standard levels in the first quarter of 2024.

Thin Malatesta, a registered nurse and assistant professor of nursing at Tan Chingfen Graduate School of Nursing, part of UMass Chan Medical School in Worcester, started her career as a staff nurse before transitioning into travel nursing. In her perspective, travel nursing has allowed for a broader understanding of the workings of hospitals.

Through her three travel contracts, she’s been able to see how operations work at systems large and small and has had exposure to more kinds of patients from different backgrounds, she said.

When she was a nurse at an intensive care unit before becoming a travel nurse, she said she had positive feelings about the temporary additions.

“Nurses appreciated it. They were there to fill in the holes,” said Malatesta.

The holes grew wider during the pandemic, and more travel nurses were needed to meet the increased demand on hospitals.

Malatesta said reactions to travel nurses vary from place to place, depending on the culture at the hospital. Some staff nurses are disgruntled by the difference in demands and pay. It’s common knowledge among nurses that travel nurses make multiples of staff nurse pay, she said.

“Hospitals have to get creative in how they're going to keep their staff,” said Malatesta.

In her role as an instructor at the graduate school of nursing, Malatesta said she urges students to start in staff positions to gain experience rather than immediately jumping into travel nursing.

“It’s not a good practice to start there,” she said.

A small pool of workers

A March 29 report from the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission suggests the nursing shortage isn’t caused by a decreased interest in entering the field. Rather, established nurses are leaving the industry.

The high pay for travel nurses is directly leaching from the pool of staff workers, said Murphy, from the MNA.

Anecdotally, the sustained reliance on travel nurses is a concern for quality of patient care, said Murphy. While the skill of the travel nurses compared to staff nurses is not the concern, the team dynamic that is critical in nursing is, she said. Building a team of nurses with varied skill sets who have knowledge of the protocols of the hospitals they work in has been a cornerstone of the nursing dynamic, said Murphy.

“Having temporary nurses parachute in for eight or 12 weeks really affects the quality of care,” said Murphy.

During the panel with the Health Policy Commission, Walsh made clear his stance on a need to return to pre-pandemic utilization of travel nurses as part of the solution to the myriad problems plaguing the healthcare industry.

“If we care about any of the other things that are important to us, we have to solve this problem,” he said.