Artificial intelligence offers ways to improve the burdensome electronic health records process, but a leading Westborough company urges caution amid innovation.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Girish Navani is comfortable with change. That's how he came to co-found eClinicalWorks, a healthcare technology company, in 1999 without a life science background. He’s always been excited about change, and that’s how he has approached technological innovation during his tenure as CEO of the Westborough company, which has long worked to change the landscape in electrical health records.

With that same excitement Navani is looking at the next change: the increased presence of artificial intelligence in health care.

“The change cannot cause chaos,” Navani said.

A measured approach needs to be taken in its implementation, and it cannot become the driving force in medical record keeping, he cautioned.

AI is a co-pilot.

That’s how Navani, Sameer Bhat, vice president and fellow eClinicalWorks cofounder, and Dr. Eric Alper, a physician at UMass Memorial Health in Worcester, all describe how artificial intelligence technology should be used in medical records.

“The AI isn't doing medicine,” said Alper, who is chief clinical informatics officer and senior vice president, chief quality officer in addition to his medical practice at UMass Memorial.

Though the technology shouldn’t take the driver’s seat, the three believe AI in medical records might be the solution physicians have been waiting for, after years of burdensome electronic health record processes.

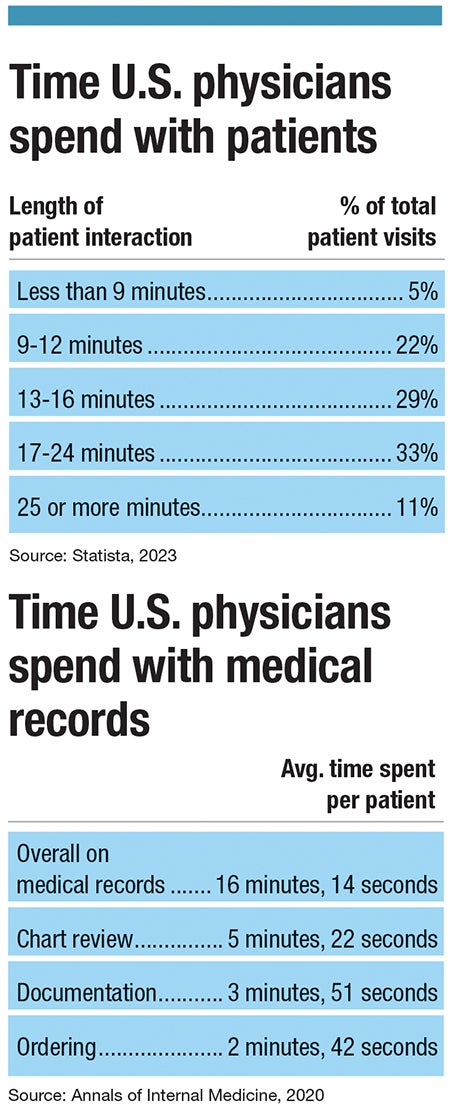

The average physician spends an equal amount of time entering medical records and processing subsequent orders after seeing a patient as they do with the patient directly, according to data from German-based online provider Statista and industry journal Annals of Internal Medicine.

For physicians who often see upwards of five patients an hour, a technology that can summarize records in advance of appointments, document information from the appointment, and create boilerplate for ordering follow-up procedures and prescriptions may alleviate or remove a significant time suck.

Solving inefficiencies

Electronic health records, EHRs, have transformed dramatically over the past 10 years, said Alper.

“It’s not just a medical record. It’s so much more than that,” he said.

EHRs facilitate a tremendous information exchange, he said, with functionality that allows sharing of important patient documentation easily. Where before physicians might have to walk across a hospital’s campus to view X-ray charts, now they are able to access them immediately.

“It's just a click away,” Alper said.

While EHRs provide benefits, they can create efficiencies in certain areas, including documentation requirements from insurance and legal departments.

At UMass Memorial, the AI technology in use is still in very early stages, said Alper. Still, he believes the technology will create a market change on EHRs across the board.

“AI as a co-pilot will be the next phase of the electronic health record,” he said.

That’s where technology like what eClinicalWorks is developing might be able to bridge a gap.

“The technology can solve 90% of that problem of inefficiency,” Bhat said.

eClinicalWorks hopes to lead the progress into that phase. At eClinicalWorks, multiple forms of the new AI are being assessed for development into the new horizon of assistive technology. One is the voice-recognition software, which physicians can use to expedite documentation processes. Some features of the voice software have been in use for several years at eClinicalWorks. Navani said this will have a larger role going forward, potentially for use as a translator.

Other developments at eClinicalWorkers include the ChatGPT model, which analyzes text and can provide summaries of a vast quantity of information. In medicine, this can be used to look at decades worth of medical information about a patient and provide a summary of their health history without a physician having to individually access and read each page of the patient’s medical records.

Taking a cautious approach

eClinicalWorks is a large company serving more than 1 million medical care providers worldwide, but it remains privately held, which is advantageous to innovations, said Navani.

“We have our own code of conduct,” he said, which centers ethics rather than shareholder expectations.

Despite the agility being private allows for, there is still a need to be cautious, said Navani, as the AI industry overall is moving at a blistering pace.

That measured response is what Alper views as necessary, too.

“Like any new tech, we need to fully understand it and fully evaluate all pros and cons,” he said.

There are safeguards in place to do this at eClinicalWorks. Responsible AI, as Bhat calls it, means the medical provider will still be asked to review the summary. The doctor is still driving the process while the AI streamlines it. Other industries are repositioning quicker to the next capabilities of AI, and while eClinicalWorks is ahead of the curve in health care, it can’t – and shouldn’t – be leading the race, Navani said.

“Healthcare moves slowly because it's dealing with human life,” he said.

At its best, AI technology can become a safeguard for physicians, too. Already in use in some aspects of medicine such as radiology, the AI works as a second pair of eyes and can catch things a physician might miss.

“It can create a safety net,” said Alper.

Always, though, AI supports physician work. It doesn’t replace it, he said.

eClinicalWorks is using an early adopter pilot program as it assesses how well AI technology is working in practice and what can be better in its next iteration. That kind of assessment will need to be part of all implementations of the new technology.

“Even more than other tech, it is important to continue to monitor its use and assure it is meeting goals,” said Alper.

The benefits AI can provide to physicians may be endless but might manifest as small, incremental changes, said Bhat, like reducing the number of clicks in certain processes.

In Alper’s perspective, those incremental changes are steps on a long path of innovation AI can bring to medicine.

“The sky's the limit in terms of what it potentially can do,” said Alper.