Maureen Dunne, co-director of the MetroWest Economic Research Center and a professor at Framingham State College, gets the feeling that the labor market situation is worse than the 9.5 percent unemployment rate the federal government released last month.

“It just seems like everyone knows someone who is out of work, or who is working part-time, or isn’t even looking for a job anymore,” she said.

And she may be right.

A broader measure of the state and federal unemployment rate, one that takes into account “discouraged workers,” or people that would like to have a full-time job but do not, is well above the 9.5-percent mark and is in fact at about 16.5 percent nationwide, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That discouraged workers unemployment rate, some economists say, is a clearer “measure of the misery,” as Dunne calls it.

Numbers Game

Despite the official state and federal unemployment rates remaining stable or slightly improving in recent months, the actual economic situation may actually be worse, according to multiple economists.

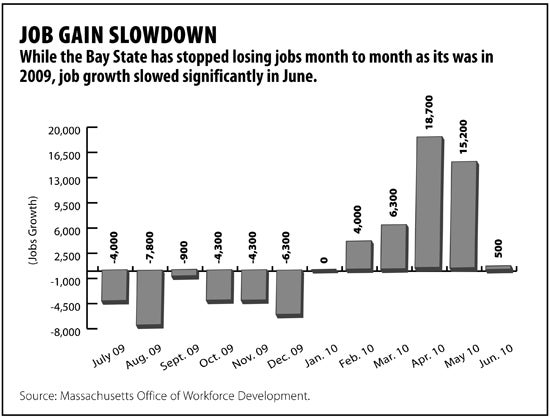

Take the latest unemployment figures released by the state last month, in which there were only 500 more people employed in Massachusetts compared to the previous month out of a labor force of about 3.1 million workers.

Still, the unemployment rate declined from 9.2 percent to 9 percent.

So how did the unemployment rate drop with such a small increase in the number of people employed?

Andrew Sum, director of the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University in Boston, said it’s because there were 8,000 fewer people who were unemployed. They didn’t get a job; they’ve just stopped looking for a job, so they are no longer technically considered part of the work force.

“The unemployment rate went down not because people found jobs, but because they quit looking for one,” he said. “There are a lot of people missing from the work force and as a result, the unemployment rate is badly undercounting the number of people who should be working.”

According to BLS figures, about 60 percent of unemployed people around the country have been without a job for more than 15 weeks.

Of those, 45 percent have been without a job for six months or more. Eventually, Sum said, people stop looking for a job because they feel they can’t find one. When that happens, the person leaves the labor force, which can artificially inflate or stabilize the unemployment rate without new jobs being created.

Fahlino Sjuib, an assistant professor of economics at FSC and MERC’s unemployment guru, said the official unemployment rate released by the government monthly needs to be taken with a grain of salt.

“Although unemployment rate is a good indicator of current conditions in the job market, a decrease in the unemployment should not be taken literally as a measure of people who want to work and actually can find jobs, especially when there is a relatively significant decrease in the labor force,” he said. “A decrease in unemployment rates might conceal deep frustration felt by the discouraged workers.”

Both the official unemployment rate and the discouraged workers unemployment rate are at levels that are more than double their values from a decade ago.