Watching the Fed: After a jump in rates over the last two years, banks are preparing for cuts to trigger more activity

Illustration | Mitchell Hayes

The Fed is expected to lower interest rates in 2024.

Illustration | Mitchell Hayes

The Fed is expected to lower interest rates in 2024.

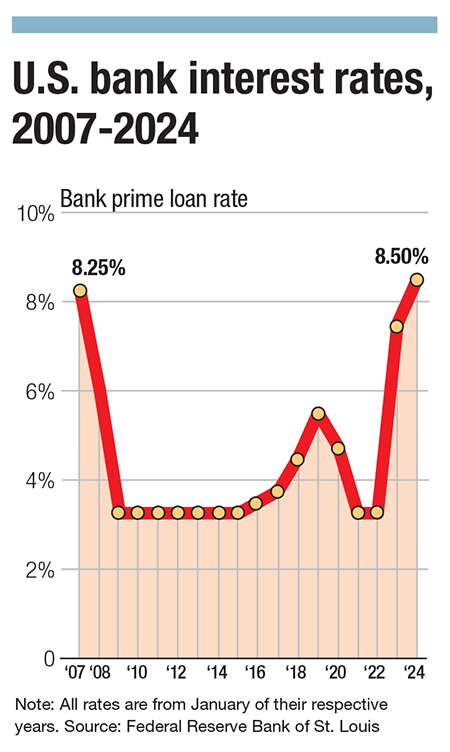

In March of 2022, the U.S. Federal Reserve began bumping up its benchmark interest rate, which had hovered around zero for much of the previous 13 years. Over the next 18 months, it raised rates 11 times, up to 5.4%.

For Central Massachusetts banks, that was a lot of change to deal with. But today, with the Fed seemingly poised to start bringing rates down this year, the banks are facing a new set of challenges.

Martin Connors, president and CEO of Fitchburg-based Rollstone Bank & Trust, said the rapid rate hikes meant the bank had to pay more to its savings customers, even though many of its loans were at fixed rates that couldn’t be raised to compensate.

“It’s not the level,” Connors said. “It’s the manner in which it got there so quickly.”

The fast pace of change was a big issue, said Derek Plourde, president and CEO of Charles River Bank, based in Medway. After months of hesitating on responding to rising inflation with a rate hike, Plourde said, the Fed ended up having to move more quickly than it might have had it started earlier.

“The reality is the Federal Reserve is always – and I don’t want this to sound harsh – but they’re usually being reactive and not proactive,” Plourde said. “They had to act much more robustly after the fact.”

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said in early February he anticipates three rate reductions this year, down to a probable rate of 4.6% by the end of the year. The first cut is expected to come in May.

Local bankers say, just like with hikes, the dangers are less in the level of change than the pace of it. But, for now, projections suggest the cuts will come at a measured pace

“In most cases people will tell you if they

cut rates, that’s a good thing,” said Brian Stewart, executive vice president and CFO of Natick-based Middlesex Savings Bank.

Big concerns in 2024

Stewart’s biggest concern is the signals the Fed may send through its actions. The bond market is in an unusual state known as an inverted yield curve, in which interest rates are higher for short-term bonds than long-term ones. If the Fed’s moves convince investors interest rates are likely to continue to fall, it could exacerbate this situation, reducing yields on long-term loans and investments.

Overall, though, lower interest rates could attract borrowers who’ve put off personal or business investments waiting for a better deal, Connors said. The prime lending rate – offered to banks’ most reliable customers – is tied directly to the Fed rate. If the Fed drops its benchmark to 4.75%, the prime rate would fall to 7.75%.

“Psychologically, you’re into the 7s, not 8s,” Connors said.

Still, customers will need time to adjust to rates likely to remain higher than they had come to expect, he said.

“It’s going to take a long time to go back to whatever normal is,” Connors said.

The Massachusetts Bankers Association expects both homebuyers and business owners to pick up borrowing activity in response to a rate cut, MBA President and CEO Kathleen Murphy said in an email to WBJ.

“While rates will not decline in 2024 to the historically low levels we saw before the pandemic, lower borrowing costs are expected to result in higher consumer and commercial loan demand,” she wrote.

The effectiveness of interest rate changes in supporting a healthy economy depends on how well they respond to complex economic factors. Where the rate hikes were a response to inflation, proposed cuts would aim to prevent the economy from cooling excessively, resulting in rising unemployment. Bank officials see contradictory signals about how big a danger that is.

“Anecdotally, some companies are cutting,” Stewart said, pointing to UPS’s January announcement of plans to cut 12,000 jobs. “But it’s not showing up in the unemployment numbers yet.”

Another potential sign of a faltering economy is rising delinquencies on loan repayments, he said. Right now, the banking industry is in a moment of unusually low credit problems, so any rise in those issues just represents getting back to normal.

“Banks need to be careful what they wish for,” Connors said, adding while a 3% rate might be ideal, if the Fed dropped rates that low it would be as a result of widespread problems like customers and businesses struggling to repay loans.

“I would rather be dealing with interest rate problems than to be dealing with foreclosing on homes, foreclosing on businesses,” he said. “It’s a cycle. We can weather the storm, but you don’t want to start throwing people out of their homes.”

Keeping the local trust

The vulnerability of banks took on new salience for lenders in spring 2022, with the collapse of regional banks Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic Bank in California and Signature Bank in New York. While the reasons for the failures were complicated, among them was the jump in interest rates, which affected the prices of bonds the banks had invested in.

“One thing the industry did learn from that is how quickly people can move their money out of a bank,” Stewart said. “It doesn’t matter how much capital you had or how profitable you are. Banking is still a confidence business.”

Central Massachusetts bankers say they’re not worried about facing the same fate as those banks regardless of economic turbulence. One reason is community banks in Massachusetts use the industry-sponsored Depositors Insurance Fund to insure deposits over the FDIC limit of $250,000. Another is local and regional banks in the area work with a balanced collection of companies in stable industries and aren’t exposed to volatile markets like cryptocurrencies. “We do traditional banking, we do it conservatively, we do it with our depositors’ interests in mind,” Plourde said. “We don’t take big swings at things that make no sense.”

Another source of trust in the area’s banks, even in the face of economic uncertainty, is their combination of up-to-date technology and a personal touch, the three Central Massachusetts bankers said.

“You want to know the people you’re doing business with,” Plourde said. “When you call, you’re going to actually speak to somebody. You can sit down with somebody.”

When it comes to the Fed’s choices, bankers say it’s important to contextualize current events within a bigger context. While current interest levels may seem shocking to borrowers who got used to rock-bottom rates in the 2010s, rates were frequently higher than they are now from the 1970s through 2000.

“I can remember my first mortgage was double digits,” Stewart said. “Historically, these aren’t high rates.”

0 Comments