Building out a bioscience startup ecosystem

Photo/Matt Wright

Jisun Lee, a postdoctoral fellow at UMass Chan Medical School, works in the Worcester school’s lab.

Photo/Matt Wright

Jisun Lee, a postdoctoral fellow at UMass Chan Medical School, works in the Worcester school’s lab.

Massachusetts has grown into the global capital for biotechnology and life sciences research. The state’s renowned hospitals like Boston Children’s Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Tufts Medical Center, and others have, in conjunction with the universities attached to them like Harvard University and Tufts University, made the area a place where innovation flourishes. While the tech industry has Silicon Valley, the biotech industry has Cambridge. But space and cost has begun to creep into the area, forcing companies, especially startups, to look outside of the Route 128 belt and increasingly more towards Central Massachusetts and its own life sciences hubs in Natick, Marlborough, and Worcester, where UMass Chan Medical School and the UMass Memorial Medical Center can provide their own beacon of research and medical practice.

So how does the money eventually start to move to the area? According to a 2022 Massachusetts Biopharma Funding Report, Massachusetts companies received $8.72 billion in venture capital funding in 2022, behind 2021’s $13.66 billion, but most of it went to companies in and around Cambridge and Boston. Cambridge received 49% of the funding while Boston got 23%. Communities like Natick and Framingham each had companies get more than $89 million in 2022, which is far less than the more than $4 billion for Cambridge or even the $916 million in Waltham, but it’s a start. And that start is happening because companies are beginning to look outside of the hub to find the space they need at a reasonable price.

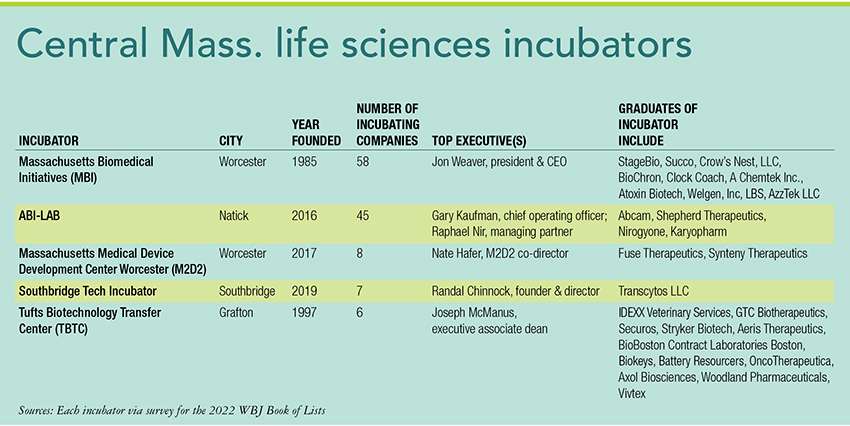

One of the places startups have begun to look is in Natick where Raphael Nir co-founded ABI-LAB with Gary Kaufman. Nir co-founded SBH Sciences, which is a Natick biotech company paying for its research by providing preclinical development research and services to other biopharmaceutical and biotech companies. He also founded SBH Diagnostics, which is a contract research organization. But what he really wanted to do was to help foster more startups, so with Kaufman, he opened ABI-LAB in September 2016.

“We built out for 15 companies and underestimated the demand,” Kaufman said.

ABI-LAB has quickly grown from one building for 15 companies to preparing to open a third in 2023.

Ripe for talent, investment

Kaufman and Nir looked at different places to open that first lab and found Natick was the sweet spot for them. It was close enough to Boston and Cambridge to bring talent and venture capital money in. They discovered a lot of the people who worked in Greater Boston lived in the MetroWest area, and they could convince them to shorten their commute and give Natick consideration to start their next venture. They built purpose-driven buildings with state-of-the-art plumbing, electricity, and HVAC, which are vital in lab settings needing specific conditions to operate.

Kaufman sees Central Massachusetts as ripe for other investment. There’s room to grow in Natick and the surrounding communities, if they have the proper sewer hookups and other utility setups necessary. It could become the next digital highway, which is what Route 128 was known as in the 1970s when technology companies began to open along the corridor as space in Boston was expensive and the suburbs proved promising for growth. Since then, people have continued to move westward. No longer is the concentration of educated and talented people living inside 128. They’re in the surrounding communities, and the push west since COVID began in 2020 has only increased this talent pool.

Jon Weaver, the president and CEO of Massachusetts Biomedical Initiatives, a life sciences incubator in Worcester, sees Central Massachusetts as ripe for investment in life sciences because the talent is here and the space is available for a more reasonable price compared to Boston and Cambridge. He sees what happened in Kendall Square as a blueprint for what can happen in other communities.

It wasn’t that long ago Kendall Square in Cambridge was an afterthought. The area was a forgotten manufacturing zone, blighted from years of neglect. There were textile, candy, and leather factories, all with diminishing returns as manufacturing began to leave the area and the country after World War II. Today, the neighborhood is the epicenter of medical and life sciences research, but that booming business and source of innovation and jobs almost didn’t happen.

In 1976, Harvard University wanted to build a new lab in the area to study gene splicing, but the then Cambridge Mayor Alfred Vellucci didn’t want it. He was scared of what this new research and technology could do. Harvard wanted to conduct recombinant DNA experiments in its proposed lab, and Vellucci didn’t want that happening in his city. A battle ensued at city hall. Vellucci tried to impose a two-year moratorium on gene splicing in Cambridge, and the city council created a board of nine Cambridge citizens and passed a three-month moratorium on the work. The board had the task of exploring if the work should be allowed and what kind of safety measures should be put into place. Eventually, the board came up with a framework for DNA-related research.

At the same time, genetic research became a hot button issue in other cities and towns. There was a feeling these experiments could run awry; they weren’t safe and could create some sort of science-fiction monster. Somerville held public hearings in 1981 where concerns were lobbied against bringing this type of research to its neighborhoods. Cambridge, in comparison, began to welcome the companies. Biogen Inc. opened in 1982, and Mayor Vellucci changed his tune.

Since then, Cambridge has become the epicenter of research and innovation in life sciences. Through partnerships with Harvard and MIT, Kendall Square has turned into ground zero for research and the future of medicine. According to investment data platform Crunchbase, 576 biotech companies operate in the Cambridge area, with an average founding date of May 2012. The area boasts world-renowned companies like Amgen Inc., the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, and Pfizer Inc.

Extending the life sciences cluster westward

What has paid off for Cambridge is the companies have clustered together. They have found space near each other, sharing talent and ideas. Spinoffs and startups built out nearby and were able to lure in employees with experience. They can connect with venture capital funding easily to fund their research. What Weaver and Kaufman envision is the cluster doesn’t have to end in Cambridge, it can extend out much like Silicon Valley has in the Bay Area of California. If you superimposed the area covered by Silicon Valley, it would cover the same space between Boston and Worcester, encompassing MetroWest with the Route 128 and I-495 belts.

In fact, there are already strong clusters in Central Massachusetts to complement those in Boston. UMass Chan Medical School has its own incubators alongside those going on at MBI. It has the Massachusetts Medical Device Development Center, which partners with UMass Lowell, as well as other companies in the incubation process.

The work going on at UMass is similar to what has happened with Harvard and MIT in Cambridge. The research hospital, which like Harvard, gives researchers the ability to seek out problems in need of solving and the resources and talent to go after those challenges. The faculty becomes a resource and can help incubators problem-solve. And with programs like the Medical Device Development Center, entrepreneurs and scientists can walk a hallway or to another building to ask for advice or work through problems with frontline workers.

The reason this is all important is because big pharmaceutical companies are continuing to spend billions of dollars on research and development, but the things they’re working on are harder to nail down. That means they need to look outside of their own structure for answers. Medicine and the technology to administer it has become more complex thanks to the research coming out of Cambridge, but that means it’s more expensive to invest in and a lot harder to see clear paths. So, pharma companies need more thinkers coming up with solutions. Parth Chakrabarti, executive vice chancellor for innovation and business development at UMass Chan, said places like UMass, MBI, ABI-LAB, and the universities in Central Massachusetts like Worcester Polytechnic Institute, which is spinning off its own companies and renting out lab space to startups and researchers, will be the bridge for those pharma companies.

“Institutions are the magnets,” Chakrabarti said.

The magnets will eventually bring money with them because venture capital is built around finding good science and scientists with the right platform and infrastructure to build around.

“The research institutions are the lifeblood of VC and startup science,” Chakrabarti said. “Dollars are an ingredient to make science. Both are needed, but the money will follow innovation.”

Between 2018 and 2023, companies in Central Massachusetts have attracted more than $833 million in venture capital funding to bring their ideas to fruition, according to Crunchbase. This includes a $150-million investment in 2018 to Littleton proton therapy company Mevion Medical Systems and a $75-million investment in 2022 to Marlborough genetic medicine developer Solid Biosciences.

All that is on top of the hundreds of millions in National Institutes of Health grant funding that Central Massachusetts organizations – led by UMass Chan and WPI – receive each year. In fiscal 2022, NIH funding exceeded $223 million in the region.

Chakrabarti sees Kendall Square and Cambridge expanding in a way that can’t hold all of the investors and industry leaders.“Kendall Square is bursting at the seams,” Chakrabarti said. So, there is a void Central Massachusetts can fill. Now, it’s about finding the rest of the ingredients to make the mix work. The talent is here, but Parth believes more needs to be lured away or nurtured to have the capital follow. To do that, the infrastructure needs to be in place. The Commuter Rail train needs to be more economically viable and less time consuming – a half-hour train ride, Chakrabarti said. Then the technology will come with lab space and more companies moving on from incubation. Eventually, the money will start to filter and see the value in investing in companies with lower overhead costs.

What’s for certain, is changing the perception of Central Massachusetts to a hotbed of life science research is going to be hard.

“The lure of the Cambridge and Boston address is there,” Nate Hafer, director of operations for the UMass Chan Center for Clinical and Translational Science and co-director of Massachusetts Medical Device Development Center. “There is a fear of missing out in some magical place. The lure is hard to overcome.”

But Hafer said the cost of real estate will be a real pull. It’s what the region has going for it alongside the solid foundation of research institutions. The talent is or has moved to Central Massachusetts. Now it’s about bringing the money along with it and seeing the project for what it is: long-term.

“If we’re in a 50-year timeline, we are in year five, and that is good,” Chakrabarti said. “There is a long way ahead, and it’s exciting. That means we have 45 years of growth ahead of us.”

WBJ Web Partners

The 'Lure' exactly right.....more fun working over at Kendall Sq . than an industrial park in Natick, I know.

1 Comments